Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Harappan Civilization and Aryan Theories - David Frawley Page 15

Enviado por

Alípio Fera AraújoDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Harappan Civilization and Aryan Theories - David Frawley Page 15

Enviado por

Alípio Fera AraújoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

THE HARAPPA / VEDA DISCUSSION (2002)

Michael Witzel Harvard University

The Hindu Open Page Historical divide: archaeology and literature Tuesday, Jan 22, 2002 N.S. RAJARAM Indology grew out of attempts to interpret Indian sources from European perspective. Its legacy is archaeology without literature for the Harappans and a literature without archaeology for the Vedic Aryans. Any rewriting of history must begin by bridging this unnatural gulf.

INDOLOGY, WHICH prominently includes history of the Vedic Age, is the result of a historical accident. In 1784, Sir William Jones, an English jurist in the employ of the British East India Company, began a study of Sanskrit to better understand the legal and political traditions of the Indian subjects. As a classical scholar, he was struck by the extraordinary similarities between Sanskrit and European languages, especially Latin and Greek. He went on to observe: "... the Sanscrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of wonderful structure, more perfect than Greek, more copious than Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of the verbs and in the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three without believing them to have sprung from the same source." Though he was not the first European to recognise this connection that honour belongs probably to Filippo Sassetti, a Florentine merchant living in Goa two centuries earlier Jones was the first to express it in scholarly terms. With this dramatic announcement Jones launched two new fields Indology and comparative linguistics, notably Indo-European linguistics. To account for this similarity, some scholars postulated that the ancestors of Indians and Europeans must at one time have lived in the same region and spoken the same language. They called this the Aryan language and their common homeland the Aryan homeland. Following the Nazi misuse of the word Aryan as a race, and the atrocities that accompanied it, the term has fallen into disfavour. The preferred term today is Indo-European. According to this theory, the ancestors of the Indians who used Vedic Sanskrit to compose the Vedas and other related literature hailed from a land outside India. Their original homeland has been placed in locations from Germany to Chinese Turkestan, that is, everywhere except India where the Vedic language and its literature have found the fullest expression and endured the longest. This is the background to the famous Aryan Invasion Theory (AIT) that has dominated Indian history books for over a century. Based on various arguments, but strongly influenced by biblical beliefs, scholars like F. Max Mueller assigned a date of 1500 BC for the Aryan invasion and 1200 BC for the composition of the Rigveda, the oldest member of the Vedic corpus. The Bible is said to assign the date October 23, 4004 BC for the Creation and 2448 BC for the Flood. This was in the background when he gave 1500 BC as the date of the Aryan invasion. Max Mueller himself in a letter to the Duke of Argyle, then acting Secretary of State for India, asserted: "I regard the account in the Genesis (of the Bible) to be simply historical." In his

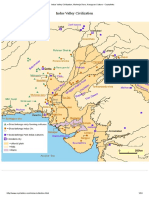

defence, it must be recognised that he was by no means dogmatic about his theories. Towards the end of his life, in response to some critics, Max Mueller wrote: "Whether the Vedic hymns were written in 1000, 1500 or 2000 or 3000 BC, no power on earth will ever determine." Mismatch What is remarkable in all this is the fact that the foundations of ancient Indian history were being laid by scholars who were not historians but linguists. In keeping with the political conditions of the age the heyday of European colonialism it was inevitable that colonial and Christian missionary interests should have intruded on their work. Even Max Mueller, during the first half of his career, saw it his duty to advance the interests of Christian missionaries, though, towards the end of his life, he became a convert to Vedanta. In addition, most of them had no scientific background witness their belief in the Biblical Creation Theory. There was also no archaeology to guide them. All these were soon to change. Beginning about 1921, Indian and British archaeologists working under Sir John Marshall revealed the existence of the ancient cities of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro in the Punjab and Sindh. Further excavation showed that they were part of a vast civilisation spread over most of North India and even beyond. This is now famous as the Indus Valley or the Harappan civilisation. They were flourishing in the period from c. 3100 BC to 1900 BC, or more than a thousand years before the postulated Aryan invasion. Scholars from a wide range of disciplines including literature, archaeology, architecture and even mathematics, began to study the archaeological remains for clues to the identity and nature of the civilisation. At first sight, the discovery of the Harappan civilisation, spread over the same geographical region as described in the Vedic literature, seemed to invalidate the Aryan Invasion Theory. The natural conclusion seemed to be that Harappan archaeology represented the material remains of the culture described in the Vedic literature. But for reasons that are too complex to detail here, prominent historians soon rejected the idea of the Vedic identity of the Harappan civilisation. They insisted that the Harappans were a pre-Vedic (and non-Vedic) people who were defeated by the invading Aryans and forced to migrate en masse to South India, later to be known as Dravidians, speaking languages that are supposedly unrelated to Sanskrit. Through this device, historians sought to preserve the Aryan Invasion Theory and reconcile it with the existence of a much older civilisation in the Vedic heartland. In this exercise it should be noted that a theory postulated by linguists in the previous century prevailed over archaeological evidence. No evidence of invasion This soon ran into contradictions. Archaeologists found no evidence of any invasion or warfare severe enough to account for the uprooting of such a vast civilisation. On the other hand, the decline of the Harappan civilisation could be attributed to natural causes in particular, ecological degradation due to the drying up of vital river systems and also floods. It is now known that a major contributor was a severe 300year drought (2200 1900 BC) that struck in an immense belt from the Aegean to China. Recent research has shown that the rainfall in some areas diminished by as much as 20 per cent. The Harappan was one of several ancient civilisations to feel

the impact of this ecological catastrophe; others similarly affected were Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia to the west and China to the east. The theory of Harappans as Dravidians has also proved to be far from satisfactory. The Harappans, who were supposed to be the original Dravidian speakers, were a literate people. There are some four thousand examples of their writing from sites like Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro, Lothal, Kalibangan and others, as well as dozens in West Asia. Yet, the earliest examples of South Indian (or Dravidian) writing use a version of the Brahmi script, which originated in North India. This leaves us in the extraordinary situation where the migrating Harappans took their language but not the script that they had themselves invented. And they waited more than a thousand years to begin their writing, borrowing from a North Indian script for the purpose. In the light of all this, the situation regarding the primary sources of ancient India may be summarised as follows: no satisfactory explanation has been found to account for the separate existence of Harappan archaeology and the Vedic literature, both of which flourished in the same geographical region. On the one hand, there is Harappan archaeology, the most extensive anywhere in the world, but no Harappan literature. On the other, there is the Vedic literature, which exceeds in volume all other ancient literature in the world combined several times over, but no Vedic archaeological remains. So we have archaeology without literature for the Harappans and literature without archaeology for the Vedic Aryans. This is all the more puzzling considering that the Harappans were a literate people while we are told that the Vedic Aryans knew no writing but used memory for preserving their immense literature. This means only the literature of the illiterates has survived. In the light of this incongruity, one may say that as long as this gulf between archaeology and literature remains unbridged, there can be no such thing as history. Neither the Harappans nor the Vedic Aryans have a historical context, but only archaeological and literary sources hanging as loose ends. So the first step in any writing (or rewriting) of ancient history should be a systematic programme to rationally connect Harappan archaeology and the Vedic literature. These are the primary sources; the theories that are now in textbooks are secondary, based on the perceptions of scholars of the colonial era. More seriously, they contradict the archaeological evidence. Vedic-Harappan connection Fortunately some progress is being made in accounting for both Harappan archaeology and the Vedic literature, though, to a large extent, it owes to the work of outsiders. Some Vedic scholars have noted that Harappan remains are replete with sacred Vedic symbols like the swastika sign, the `OM' sign and the sacred ashvattha leaf (Ficus Religiosa). No less dramatic is the discovery of the American mathematician and historian of science, A. Seidenberg, tracing the origins of Egyptian and Old Babylonian mathematics to Vedic mathematical texts known as the Sulbasutras. As Seidenberg observed: " ... the elements of ancient geometry found in Egypt (before 2100 BC) and Babylonia (c. 1900 1750 BC) stem from a ritual system of the kind observed in the Sulbasutras." This means that the mathematics of the Sulbasutras, which are Vedic texts, must have existed long before 2000 BC, i.e., during the Harappan period. This is clear also from a technical examination of Harappan archaeology, which displays skill in town planning and geometric design, showing that Harappans must have had access to the Sulbasutras. This gives a

scientific link between Vedic literature (Sulbasutras) and Harappan archaeology. (The Sulbasutras should not be confused with popular books on Vedic mathematics. These are modern works that have little to do with the Vedas). All this shows that progress can be made in explaining Harappan archaeology and the Vedic literature if one is prepared to follow a multidisciplinary, scientifically rigorous approach. The present incongruous situation of mismatch between archaeology and literature is attributable to two factors. First, an attempt to preserve a theory created on the basis of insufficient evidence before any archaeological data became available. Next, the fact that even this theory and the foundation that it rests on were created by linguists and other scholars whose understanding of science and the scientific method left much to be desired. Correcting past errors Several historians have rightly expressed concern that history may soon be written by individuals who lack the necessary knowledge of the historical method. But far more serious is the fact that what is found in textbooks today is based on theories created by men and women who had no qualifications to write about them. They are based not on the primary sources, but explanations that seek to fit the data to a particular Nineteenth century worldview the Eurocolonial. The immediate task before Indian historians is to get back to the fundamentals, ignoring the authority of scholars from the past, no matter how great their reputations. Sri Aurobindo suggested that the problem lies in the failure of Indian scholars to develop independent schools of thought. In his words: "That Indian scholars have not been able to form themselves into a great and independent school of learning is due to two causes: the miserable scantiness of the mastery in Sanskrit provided by our universities, crippling to all but born scholars, and our lack of sturdy independence which makes us over-ready to defer to European (and Western) authority." This is not to suggest that we should either deny or reject the findings of Western scholarship. Only we should not accept them uncritically as authority figures. They were products of their time and environment and the resulting weaknesses should be recognised. Their contributions remain substantial, but cannot be treated as primary knowledge. No less a person than Swami Vivekananda once said: "Study Sanskrit, but along with it study Western sciences as well. Learn accuracy, ... study and labour so that the time will come when you can put our history on a scientific basis... How can foreigners, who understand very little of our manners and customs, or our religion and philosophy, write faithful and unbiased histories of India? ... Nevertheless they have shown us how to proceed making researches into our ancient history. Now it is for us to strike out an independent path of historical research for ourselves, ... It is for Indians to write Indian history." His advice holds as good today as it did a century ago when he gave it to a group of students. The recovery of history must begin with a thorough study of the primary sources. The first step is to close the unnatural gap between archaeology and literature. N.S. RAJARAM (The writer is the author with David Frawley of the book Vedic Aryans and the Origins of Civilisation)

The Hindu Open Page Tuesday, Jan 29, 2002

Indus Civilisation and Vedic society MICHAEL WITZEL The Open Page write-up by N.S. Rajaram (Historical divide: archaeology and literature, January 22) is a serious misrepresentation of the results of various fields of scholarship. Certainly, the writing of ancient Indian history "must begin with a thorough study of the primary sources. The first step is to close the unnatural gap between archaeology and literature." However, such study, which is not altogether new, has to begin without prejudices of any kind, such as Rajaram's wrong presuppositions. There is little overlap between the archaeology of the Indus Civilisation (its script cannot be read yet) and early Vedic texts. For a good reason. The oldest Vedic text, the Rigveda, is full of quick, spoked-wheel horse-drawn chariots (invented around 2000 BCE), and obviously, of domesticated horses (first clearly identified in the Kachi Plains of the Indus, at 1700 BCE), but it does not yet know of iron (introduced in the northwest around 1200/1000 BCE). Annoying details Clearly, the Rigveda must fall between these dates. However the Indus (Harappan) Civilisation is dated by all archaeologists between 2600 (not 3100!) and 1900 BCE. No wonder there is geographical but not a temporal overlap between the two. Further, in spite of recent rewriters of history, whatever the pastoral Rigveda describes does not fit the fully developed cities of the Harappan Civilisation: these are two different worlds. How to explain this `gap' is another matter, with which scholars still struggle. Whether the decline of the Indus Civilisation was due to drought or a number of separate, coinciding, and self-reinforcing reasons is still undecided. Rajaram, however, simply overlooks such annoying details by adducing various isolated features in mono-lateral fashion, features which do not add up and are in fact to be contradicted by the various sciences that he evokes against mere students of the humanities (such as me). For the details, such as on geometry, astronomy, archaeology, Puranic king lists, language, etc., see EJVS 7-3 (in Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies, http://users.primushost.com/ india/ejvs/). That the Harappans lost their script and language and took over an Indo-Aryan language (now developed into Punjabi, Sindhi, etc.) has parallels in other areas. Witness the descendants of the great Maya Civilisation who mostly speak Spanish now and have long lost their script. Their civilisation was disintegrating on its own when the Spanish arrived, who did not have to resort to the same brutal methods they used in Mexico and Peru. Civilisations do die when under strains of various sorts. Why then such a "simple" solution, a "systematic programme to rationally connect Harappan archaeology and the Vedic literature"? No Aryans were needed for the demise. The earliest Aryan-like culture in the subcontinent may be the Gandhara Grave Culture of N. Pakistan (starting around 1700 BCE), well within the time frame

mentioned above. The "Aryans", perhaps Pathan-like seasonal pastoral migrants from Afghanistan, merely exploited a new opportunity in the then less agricultural Indus Valley, and set off a wave of acculturation based on their more effective pastoralism. No Hun-like "invasion" (the model of the 19th century scholars) is needed, though one has to take into account a whole range of processes, from peaceful acculturation to forceful take-over, in the various parts of the Northwest. As history teaches, one size does not fit them all. Unilateral points The several unilateral points and the new theories built on them by Rajaram are quickly destroyed by the various sciences, such as his pre-Indus Rigveda with chariots and horses in the subcontinent before their time. Any linguist will tell him that the Indo-Aryan languages (from Punjabi to Sinhala and Bengali), Dravidian (Tamil, Telugu, etc.), Munda (Santali, etc.) belong to three completely different families that share only loan-words from Sanskrit or Prakrit, just like all European languages have theirs from Latin. Still, no Kannada or Santali speaker will understand a Punjabi, just as little as a Portuguese can make out anything from Finnish or Basque. But then, linguistics is a `petty conjectural science' as he likes to say. All his "proofs" (the ubiquitous swastika, the `literate' Harappans, seafaring Rigvedic people, the age of the Sulbasutras, Vedic literature as larger than "all other...ancient literature...combined...", etc.) disappear once one takes a closer look (details in EJVS vol. 7-3, 2001, as above). Again, the Harappans must not "have had access to the Sulbasutras" the Egyptians built their giant pyramids or a completely new, wellplanned town such as Amarna, without their help, having learned from trial and error. To what extent Rajaram must go to make the overlap between Vedic and Harappan, is exposed in Frontline, Oct. 13 and Nov. 11, 2000: http://www.flonnet.com/fl1720/fl172000.htm The historical background is wrong as well. Indology is not an "attempt to interpret Indian sources from [a] European perspective" , instead, it is an attempt to let the sources speak for themselves, irrespective of later Indian or European interpretations. In other words, just like Sinology, Egyptology, etc., it is a work in progress. Even poor old Max Mueller is misrepresented again. His history is not derived from the Bible. Anybody who actually reads his letters (not just excerpts) will see that he was, as a young man, an opportunist who wrote one "Christian" letter to his pious donor and a completely "non-Christian" letter upon the death of young sister... to his own mother. To put Indology down to "Eurocolonial attitudes" is much too facile, in fact, pure propaganda. Non-Western scholars (say, of Japan) do not agree with Rajaram's "new history" either see: "Was there an Aryan invasion at all" (in Japanese language): Kokusai Nihon Bunka Kenkyu Senta Kiyo. (Nihon Kenkyu) 23, March 2000. MICHAEL WITZEL Department of Sanskrit, Harvard University

The Hindu Open Page Tuesday, Feb 05, 2002 Vedic-Indus debate: save Indian civilisation today If the BJP and the VHP want to ensure that modern Indian civilisation is creative and dynamic, it will not be through historical debate. They should call for an immediate halt to English-medium education at all levels and the insidious class division it creates, and promote dynamic modern civilisational creativity in the Indian people's languages. The Open Page discussion on Indus and Vedic society by N. S. Rajaram (January 22) and Michael Witzel (January 29) is not finished. Rajaram's main thesis seems to be that the Indus Civilisation was a direct linear antecedent to Vedic society and classical Indian civilisation. Witzel is correct that this is too facile and appears to be an argument driven by ideology. But neither Rajaram nor Witzel discusses language much, except that Rajaram ridicules the claim that the Indus Civilisation had a Dravidian-type language saying that it is strange that the people would have lost their script. He suggests, without evidence, that it was Indo-Aryan speaking. Witzel is correct in saying that the population of the Indus Valley lost their language and script and took over an IndoAryan language which has now developed into Punjabi, Sindhi, etc. Scholars who have devoted many years to the study of the Indus script mostly agree that all indications are that it was Dravidian-like. This is the conclusion of scholars in Finland, Russia, England, Czech Republic, the U.S., Pakistan and India. Some earlier ones, like Father Heras, and recently Finnish scholars, have spent decades studying the 600 script symbols, their possible grammatical positions, and the cultural associations. It is a minority of people who are themselves speakers of Indo-Aryan languages, who assert that the Indus people must have spoken a language like that of their own! Linguistic evidence The evidence that the Indus language was Dravidian-like is overwhelming, both circumstantial and linguistic. First, there are the Brahui people, over a million who live in east-central Baluchistan. This writer has looked into the matter himself while in Baluchistan; the language is certainly Dravidian at its core. How did it get there? Nobody has seriously suggested that the Brahuis moved there from peninsular India; rather Brahui language and culture got isolated in those hills while major changes took place in Sindh and Punjab plains. And we should note the place names of Dravidian origin over Pakistan and western and central India. Many place names have the ending aar (river), or include the words mala (mountain), kandh (hill), kotta (wall or fort), besides of course uur, pura and others. Rajaram would do well to study the Dravidian Etymological Dictionary

which compiles the vocabularies of some 20 Dravidian languages, and note the geographic implications. The word uur (town) almost certainly goes back to the earliest civilisations in Mesopotamia one of the numerous indications that the basic features of civilisation (i.e. urban life) in the Indus region diffused there from what are now Iraq and Iran. Probably Dravidian languages also had antecedents to some extent in those regions. This is the thesis of a book Dravidians and the West (Lahovery), and though it makes bolder assumptions than would be allowed by the strict procedures of many historical linguists, nevertheless it presents overwhelming suggestions. If it is accepted that the hundreds of native American languages branched off from three main stems (Greenberg), and if similar efforts showing that all the languages of North Asia and Europe could have branched off from a few prototype languages, then the above suggestions about the origin of Dravidian languages should also be accepted. Rajaram thought it was strange that the Indus people lost their script. There is nothing historically strange in that the script was already weakened as the Indus Civilisation people established their many settlements in Gujarat about 2000 BC. But several of the symbols, such as swastika, fish and trident, were retained in culture and scratched onto pottery. It is absolutely clear (F. Southworth) that Marathi, though classified now as an Indo-Aryan language, is built on a Dravidian-underlying stratum. This is true to some extent for Gujarati and Sindhi also, and for that matter Punjabi and all western Indo-Aryan languages, which are universally acknowledged by historical linguists to have considerable Dravidian influence in phonetics, vocabulary and syntax. It is clear also that Dravidian languages diffused over much of Madhya Pradesh there are the place names, besides many ("tribal") peoples who still speak Dravidian languages and whose historical traditions say they moved from western to central and east-central India. Dravidian languages diffused from Maharashtra through Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, while Telugu had branched off the language tree somewhat earlier. Language displacement It is nothing unusual in history that Indo-Aryan speech overwhelmed Dravidian in western South Asia. Such tendencies are everywhere. Semitic languages overwhelmed other language groups over much of the Near East about 2000 BC, but this doesn't mean that the pre-Semitic people were killed off; rather they were often absorbed into different political-economic systems. Semitic speech later overwhelmed Egypt, then most of North Africa, because it was thought to be the vehicle of advancement. This is the usual stuff of history. In Pakistan, the Burushaski language is related to none other, isolated in the high Hunza valley. It might be a relic of both pre-Dravidian and pre-Indo-Aryan speech in Punjab. The Dardic languages, including Kashmiri, are apparently descended from the first wave of Indo-European speech to enter South Asia, but these then got isolated in the Himalayas during the diffusion of Indo-Aryan. Indo-Aryan itself got overwhelmed in western Pakistan by the later arriving Persian-related languages such as Pashto and Baluchi. These changes may happen by invasion, but also by dribbles of more mobile or more politically powerful people moving in or by their

cultures being considered so modernising that the existing inhabitants lose their language. A different language displacement was going on in eastern India. Underlying Bengali is a Munda-type language, of which Bengali today retains many linguistic and cultural evidences. There is absolutely no evidence that Dravidian speech underlies Bengali, Oriya, or Assamese (Grierson, writing on this a century ago, was wrong). The Munda languages (Mon-Khmer group) reflect diffusion of cultures from Southeast Asia thousands of years BC which had mastered horticulture (rice, bananas, turmeric, taro, etc.) and therefore enabled humans to proliferate and diffuse into eastern and central Ganga plains and east-central India with all their cultigens prior to the diffusion there of both Dravidian and Indo-Aryan. And in Southeast Asia, it was only a thousand or so years ago that Burmese, Thai and Lao languages from South China overwhelmed the Mon-Khmer languages in most of Myanmar, Thailand and Laos, not to speak of Vietnam where it happened in the south only a couple centuries ago. And before diffusion of the Mon-Khmer, the Malay languages had been more widespread. Most Southeast Asian people today accept that various underlying streams have formed their cultures and languages. So the people of India today should gladly acknowledge, as Witzel says, that Dravidian, Munda and Indo-Aryan are distinct underlying streams and the 4th one is the Tibeto-Burmese stream in the north and east. Classical Indian Civilisation had creative achievements, which are remarkable enough, without a bogus claim that it is exclusively descended from the Indus Civilisation. The real issue The real issue now is not rewriting history, but how to reinvigorate Indian civilisational creativity in modern concepts. What is to be done about the fact that six Indian languages have more native speakers than French, but in these languages there is hardly anything produced that makes a worldwide mark in modern concepts and science. I want to emphasise that practically no people in world history have made a lasting civilisational mark using the language of a minority elite; either the language of the people develops as the vehicle of modernisation (like all of the languages of Europe when they threw off Latin, and like Korean in recent decades) or that language fades as a minority elite and then the bulk of the people adopt an outside language for modernisation. The people of India should have made the choice 50 years ago. A firm decision then should have been taken that the people's languages are the vehicles of modernisation, and to be used as the medium of modern education at all levels. Then all modern currents of thought, science, and creativity would flow through the whole population as happens in all the European and East Asian languages today. The genius of civilisation would flow from the whole population, with far less class division. If the BJP and the VHP want to ensure that modern Indian civilisation is creative and dynamic, it will not be through historical debate. They should call for an immediate halt to English-medium education at all levels and the insidious class division it

creates, and promote dynamic modern civilisational creativity in the Indian people's languages. CLARENCE MALONEY

The Hindu Open Page Tuesday, Feb 19, 2002 Theory and evidence N.S. RAJARAM A historical theory must account for all the evidence and not selectively accept and ignore data. Further, a man-made theory cannot substitute for primary data.

ALBERT EINSTEIN once said: "A theory must not contradict empirical facts." He was speaking in the context of science, especially how historians of science often lacked proper understanding of the scientific process. As he saw it the problem was: "Nearly all historians of science are philologists (linguists) and do not comprehend what physicists were aiming at, how they thought and wrestled with these problems." When such is the situation in physics where problems are clear-cut, it is not surprising to see issues in a subject like history being much more contentious. This is particularly the case when trying to understand the records of people far removed from us in time like the creators of the Vedic and Harappan civilisations. As a result of some recent historical developments like European colonisation and Western interest in Sanskrit language and linguistics, several myths and conjectures, through the force of repetition, have come to acquire the status of historical facts. It is time to re-evaluate these in the light of new evidence and more scientific approaches. When we come to these myths, none is more persistent than the one about "No horse at Harappa." This has now been supplemented by another claim that the spoke-wheel was unknown to the Harappans. The point of these claims is that without the horse and the spoke-wheel the Harappans were militarily vulnerable to the invading Aryan hordes who moved on speedy, horse-drawn chariots with spokewheels. This claim is not supported by facts an examination of the evidence shows that both the spoke-wheel and the horse were widely used by the Harappans. (The idea seems to be borrowed from the destruction of Native American civilisations by the Spanish and Portuguese `conquistadors'. The conquistadors though never used chariots). As far as the spoke-wheel is concerned, B.B. Lal, former Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India, records finding terracotta wheels at various Harappan

sites. In his words: "The painted lines (spokes) converge at the central hub, and thus leave no doubt about their representing the spokes of the wheel. ... another example is reproduced from Kalibangan, a well-known Harappan site in Rajasthan, in which too the painted lines converge at the hub. ... two examples from Banawali (another Harappan site), in which the spokes are not painted but are shown in low relief" (The Sarasvati Keeps Flowing, Aryan Books, Delhi, pages 72-3). It is also worth noting that the depiction of the spoke-wheel is quite common on Harappan seals. Horse and Vedic symbolism The horse and the cow are mentioned often in the Rigveda, though they commonly carry symbolic rather than physical meaning. There is widespread misconception that the absence of the horse at Harappan sites shows that horses were unknown in India until the invading Aryans brought them. Such `argument by absence' is hazardous at best. To take an example, the bull is quite common on the seals, but the cow is never represented. We cannot from this conclude that the Harappans raised bulls but were ignorant of the cow. In any event, depictions of the horse are known at Harappan sites, though rare. It is possible that there was some kind of religious taboo that prevented the Harappans from using cows and horses in their art. More fundamentally, it is incorrect to say that horses were unknown to the Harappans. The recently released encyclopedia The Dawn of Indian Civilisation, Volume 1, Part 1 observes (pages 344-5): "... the horse was widely domesticated and used in India during the third millennium BC over most of the area covered by the IndusSarasavati (or Harappan) Civilisation. Archaeologically this is most significant since the evidence is widespread and not isolated." This is not the full story. Sir John Marshall, Director General of the Archaeological Survey when Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro were being excavated, recorded the presence of what he called the `Mohenjo-Daro horse'. Giving salient measurements, comparing it to other known specimens, he wrote: "It will be seen that there is a considerable degree of similarity between these various examples and it is probable the Anau horse, the Mohenjo-Daro horse, and the example of Equus caballus of the Zoological Survey of India, are all of the type of the `Indian country bred', a small breed of horse, the Anau horse being slightly smaller than the others." (MohenjoDaro and the Indus Civilisation, volume II, page 654). It is important to recognise that this is much stronger evidence than mere artefacts, which are artists' reproductions and not anatomical specimens that can be subjected to scientific examination. Actually, the Harappans knew the horse and the whole issue of the `Harappan horse' is irrelevant. In order to prove that the Vedas are of foreign origin, (and the horse came from Central Asia) one must produce positive evidence: it should be possible to show that the horse described in the Rigveda was brought from Central Asia. This is contradicted by the Rigveda itself. In verse I.162.18, the Rigveda describes the horse as having 34 ribs (17 pairs), while the Central Asian horse has 18 pairs (36) of ribs. We find a similar description in the Yajurveda also. This means that the horse described in the Vedas is the native Indian breed (with 34 ribs) and not the Central Asian variety. Fossil remains of Equus Sivalensis (the `Siwalik horse') show that the 34-ribbed horse has been known in India going back tens of thousands of years. This makes the whole argument based on "No horse at Harappa" irrelevant. The Vedic horse is a native Indian breed and not the Central

Asian horse. As a result, far from supporting any Aryan invasion, the horse evidence furnishes one of its strongest refutations. All this suggests that man-made theories (like "No Harappan horse") and those in linguistics cannot be used to override primary evidence like the Vedic Sarasvati (described below) and the dominant oceanic symbolism found in the Vedas. To see this we may note that South Indian languages like Kannada and Tamil have indigenous (desi) word for the horse kudurai suggesting that the horse has long been native to the region. The same is true of the tiger (puli and huli) and the elephant (aaney). Contrast this with the word for the lion simha and singam that are borrowed from Sanskrit, indicating that the lion was not native to the South. A man-made theory in linguistics, because it is not bound by laws of nature, can be made to cut both ways. It cannot take the place of evidence. Primary evidence In any field it is important to take into account all the evidence, especially evidence of a fundamental nature. This can be illustrated with the help of what we now know about the Vedic river known as the Sarasvati. The Rigveda describes the Sarasvati as the greatest and the holiest of rivers as ambitame, naditame, devitame (best of mothers, best of rivers, best goddess). Satellite photographs as well as field explorations by archaeologists, notably the great expedition led by the late V.S. Wakankar, have shown that a great river answering to the description of the Sarasvati in the Rigveda (flowing `from the mountains to the sea') did indeed exist thousands of years ago. After many vicissitudes due to tectonic and other changes, it dried up completely by 1900 BC. This raises a fundamental question: how could the Aryans who are supposed to have arrived in India only in 1500 BC, and composed their Vedic hymns c. 1200 BC, have described and extolled a river that had disappeared five hundred years earlier? In addition, numerous Harappan sites have been found along the course of the now dry Sarasvati, which further strengthens the Vedic-Harappan connection. As a result, the Indus (or Harappan) Civilisation is more properly called the Indus-Sarasvati Civilisation. The basic point of all this: we cannot construct a theory focusing on a few relatively minor details like the spoke-wheel while ignoring important, even monumental evidence like the Sarasvati river and the oceanic symbolism that dominates the Rigveda. (This shows that the Vedic people could not have come from a land-locked region like Afghanistan or Central Asia). A historical theory, no less than a scientific theory, must take into account all available evidence. No less important, a manmade theory cannot take the place of primary evidence like the Sarasvati river or the oceanic descriptions in the Rigveda. This brings us back to Einstein "A theory must not contradict empirical facts." Nor can it ignore primary evidence. N.S. RAJARAM

The Hindu Open Page Tuesday, Mar 05, 2002 Harappan horse myths and the sciences The horses found in the early excavations at Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa do not come from secure levels and such `horse' bones, in most cases, found their way into deposits through erosional cutting and refilling, disturbing the archaeological layers.

In the Open Page of February 19, N.S. Rajaram posits a truism "A theory must not contradict empirical facts," but he then does not deliver on the `empirical facts.' As a scientist, he must suffer to be corrected, bluntly this time, by a mere philologist and Indologist. Philology, incidentally, is not the same as linguistics, as he says, but the study of a civilisation based on its texts. In order to understand such texts, one must acquire the necessary knowledge in all relevant fields, from astronomy to zoology. It is precisely a proper background in zoology, particularly in palaeontology, that is badly lacking in Rajaram's, the scientist's, account. Instead, it is he, and not his favourite straw man, the Indologist, who has created some new "myths and conjectures ... through the force of repetition." Let us deconstruct them one by one. Harappan horses? To begin with, he claims that "both the spoke-wheel and the horse were widely used by the Harappans." He quotes S.P. Gupta, without naming him, from a recent book (The Dawn of Indian Civilisation, ed. by G.C. Pande, 1999). According to Gupta the horse (Equus caballus) "was widely domesticated and used in India during the third millennium BC over most of the area covered by the Indus-Sarasvati (or Harappan) Civilisation. Archaeologically this is most significant since the evidence is widespread and not isolated." Nothing in this assertion is correct, even if or rather because it comes from an archaeologist and inventive rewriter of history, S.P. Gupta. For example, the horses found in the early excavations at Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa do not come from secure levels and such `horse' bones, in most cases, found their way into deposits through erosional cutting and refilling, disturbing the archaeological layers. Indeed, not one clear example of horse bones exists in the Indus excavations and elsewhere in North India before c. 1800 BCE (R. Meadow and A. Patel 1997, Meadow 1996: 405, 1998). Such `horse' skeletons have not been properly reported from distinct and secure archaeological layers, and worse, they have not been compared with relevant collections of ancient skeletons and modern horses (Meadow 1996: 392). Instead, well recorded and stratified finds of horse figures and later on, of horse bones (along with the imported camel and donkey), first occur in the Kachi plain on the border of Sindh/E. Baluchistan (c. 1800-1500 BCE), when the mature Indus Civilisation had already disintegrated. Even more importantly, the only true native equid of South Asia is the untamable khur (Equus hemionus, onager/half-ass) that still tenuously survives in the Rann of Kutch. Both share a common ancestor which is now put at ca. 1.72 million years ago (while the first Equus specimen is attested already 3.7 mya.). The differences between a half-ass skeleton and that of a horse are so small that one needs a

trained specialist plus the lucky find of the lower forelegs of a horse/onager to determine which is which, for "bones of a larger khur will overlap in size with those of a small horse, and bones of a small khur will overlap in size with those of a donkey." (Meadow 1996: 406). To merely compare sizes, as Rajaram does following the dubious decades old Harappan data of Marshall, and then to connect the long gone "Equus Sivalensis" with the so-called "Anau horse", resulting in the "Indian country" type, is just another blunder, but Rajaram, the scientist, is not aware of it. Proper judgment is not possible as long as none of the above precautions are taken, and when as is often done just incomplete skeletons or teeth are compared, all of which is done without the benefit of a suitable collection of standard sets of onager, donkey and horse skeletons. Rajaram and his fellow rewriters of history thus are free to turn any local half-ass into a Harappan horse, just as he has already done (see Frontline, Oct./Nov. 2000) with his half-bull. Further, the archaeologists claiming to have found horses in Indus sites are not trained zoologists or palaeontologists. When I need to get my teeth fixed I do not go to a veterinarian or a beauty salon. Typically, S.P. Gupta (1999) does not add any new evidence, and just repeats palaeontologically unsubstantiated claims that are, to quote Rajaram, "myths and conjectures... through the force of repetition." The Siwalik equid In addition, Rajaram conjures up another phantom, the Siwalik horse: "fossil remains of Equus Sivalensis (the `Siwalik horse') show that the 34-ribbed horse has been known in India going back tens of thousands of years." Standard palaeontology handbooks (B.J. MacFadden, Fossil Horses, 1992) would have told him that the Siwalik horse, first found in the northern hills of Pakistan, is not just "going back tens of thousands of years" but is in fact 2.6 million years old. However, it has long died out during the last Ice Age, as part of the late Pleistocene megafaunal extinction of about 10,000 years ago (i.e. at the end of the Late Upper Pleistocene, 75-10,000 y.a.: it is reportedly found in middle to late Pleistocene locations in the Siwaliks and in Tamil Nadu, and recently, as a "Great Indian horse" in Andhra, 75,000 y.a.). But there is, to my knowledge, no account of a Siwalik horse that even remotely approaches the date of the Indus Civilisation nor does Rajaram quote any authority to this effect. Nevertheless, in order to bolster his claim for the antiquity of the "Vedic horse (as) a native Indian breed", he connects this dead horse with the Rigvedic one, which is described as having 34 ribs (Rigveda 1.162.18). But, while horses (Equus caballus) generally have 18 ribs on each side, this can individually vary with 17 on just one or on both sides. This is not a genetically inherited trait. Such is also the case with the equally variable (5 instead of 6) lumbar vertebrae, as found in some early domestic horses in Egypt (2nd. mill. BCE) and in the closely related modern Central Asian Przewalski horse (which shares the same ancestor, 620-320,000 years ago, with the domestic horse/Equus ferus). As for the number 34, numeral symbolism may play a role in this Rigveda passage dealing with a horse sacrificed for the gods. The number of gods in the Rigveda is 33 or 33+1, which obviously corresponds to the 34 ribs of the horse, that in turn is

speculatively brought into connection with all the gods, many of whom are mentioned by name (Rigveda 1.162-3). But this is mere philology, not worthy of "scientific" study... In sum, even S. Bokonyi, the palaeontologist who sought to identify a horse skeleton at the Surkotada site of the Indus Civilisation, stated that "horses reached the Indian subcontinent in an already domesticated form coming from the Inner Asiatic horse domestication centers" just as they were imported into the ancient Near East about 2000 BCE. Any zoological handbook would have told the scientist Rajaram the same (MacFadden 1992). In addition, the identification the Surkotada equid as horse by S. Bokonyi is disputed by R. Meadow and A. Patel (1997). Even if this were indeed the only archaeologically and palaeontologically secure Indus horse available so far, it would not turn the Indus Civilisation into one teeming with horses (as the Rigveda indeed is, a few hundred years later). A tiger skeleton in the Roman Colosseum does not make this Asian predator a natural inhabitant of Italy. In short, to state that the "Vedic horse is a native Indian breed and not the Central Asian horse" is just another fantasy of the current rewriters of Indian history. Nevertheless, Rajaram even repeats some of his own "myths and conjectures, (which) through the force of repetition, have come to acquire the status of historical facts," namely the old canard that "depictions of the horse are known at Harappan sites, though rare" a case of fraud and fantasy that has been exploded more than a year ago in Frontline (Oct./Nov. 2000). Apparently, he thinks, along with other politicians, that repeating an untruth long enough will turn it into a fact. Spoke-wheeled chariots Rajaram, in dire need of `Rigvedic' horse-drawn chariots for the Harappan period, then introduces spoked wheels into the Indus Civilisation: "terracotta wheels at various Harappan sites. ... The painted lines (spokes) converge at the central hub, and thus leave no doubt about their representing the spokes of the wheel." The handful existing specimens of such terracotta disks may indeed look, even to a trained archaeologist, like a spoked wheel especially when he wants to find Aryan chariots, just like Aryan fire altars, all over the Indus area. But, they may just as well have been simple spindle whorls, used in spinning very real yarn, not wild Aryan tales. Further, "spoked wheel patterns" occur in cultures that never had the wheel, such as pre-Columbian North American civilisations. In other words, all of this proves nothing as long as we do not find a pair of these "spoked wheels" in situ, along with a Harappan toy cart. Normally, the wheels of such toy carts are of the heavy, full wheel type (that is made of three interlocked wood blocks). Rajaram then asserts, for good measure, that the "depiction of the spoke-wheel is quite common on Harappan seals." This refers to the wheel-like signs in Harappan script. Unfortunately, these "wheels" can easily be explained as unrelated artistic designs (like in the N. American case). Worse, they mostly are oblong ovals, not circles. A Harappan businessman using a cart with such wheels would have gotten seasick pretty soon. They are unfit for travel and for the discerning reader's consumption.

Instead, the rich Rigvedic materials dealing with the horse-drawn chariot and chariot races do not fit at all with Indus dates (2600-1900 BCE) and rather put this text and its chariots well after c. 2000 BCE, the archaeologically accepted timeframe of the invention of the spoke-wheeled chariot in the northern steppes and in the Near East. Again, Rajaram's fantasised "Late Vedic" Indus people have scored a "first": they invented the chariot long before archaeologists can find it anywhere on the planet! "Aryan" chariots There is no need to go deeply into his building up the straw man of Aryan invasions (i.e. immigration of speakers of Indo-Aryan), involving a need to "prove that the Vedas are of foreign origin." No one today maintains such a theory anyhow. Instead, the Rigveda is a text of the Greater Punjab, indicating a lot of local acculturation but using a language and poetics that go back to the earlier Indo-Iranian period in Central Asia (c. 2000 BCE). Equally misleading is his caricature: "without the horse and the spoke-wheel the Harappans were militarily vulnerable to the invading Aryan hordes who moved on speedy, horse-drawn chariots with spoke-wheels." As has been mentioned here a few weeks ago, nobody today claims that the Indo-Aryan speakers arrived on the scene when the mature Indus Civilisation still was flourishing and destroyed it, it in whatever fashion. Instead, there is a gap of some centuries between the two cultures, as the descriptions of ruins and simple mud wall/palisade forts (pur) in the Rigveda indicate. Vedic texts tell us that the pastoralist Indo-Aryan nobility fought from chariots, and the commoners on horseback and on foot, with the local people (dasyu) of the small, post-Harappan settlements who, like the Kikata, are said not even to understand "the use of cows." Next to warfare there also was peaceful acculturation of the various peoples in the Greater Punjab, as is shown by the Rigveda itself. As for a chariot use, a brief study of ancient Near Eastern warfare would have done the `historian' Rajaram some good. It is clear to even a superficial reader that after c. 1600 BCE the Hyksos, Hittites, etc., used such chariots, not just for show and sport but also in battle, such as in the famous battle of Kadesh between the Hittites and Egyptians in 1300 BCE. Chariots were in fact used as late as in Alexander's battle with Poros (Paurava) in the Punjab, or by the contemporary Magadha army with its 3,000 elephants and 2,000 chariots. Why then all this diatribe about the "Aryan" use of chariots in favourable, flat terrain? (Not, of course, while "thundering down the Khyber Pass"!) Foray into linguistics Mercifully, Rajaram has spared us, this time, his usual assaults on the "pseudoscience" of linguistics, and instead tries his own hand at it, and teaches us some Dravidian: kudirai `horse,' which should prove that the horse has been native to South India forever. However, his foray into linguistics is incomplete and misleading. First, Tamil kutirai, Kannada kudire, Telugu kudira, etc. have been compared by linguists, decades ago, with ancient Near Eastern words: Elamite kutira `bearer', kuti `to bear.' The Drav. words Brahui (h)ullii `horse' and Tam. ivuLi are derived from `half-ass, hemion' (T. Burrow in 1972). Both words, far from being `native South Indian', thus were coming in from the northwest.

Second, other Indian language families have such `foreign' words as seen in Munda (Koraput) kurtag, (Korku) gurgi, kurki, (Sabara/Sora) kurtaa, (Gadaba) krutaa, which are all derived from Tibeto-Burmese, for example Tsangla (Bhutan) kurtaa, Tib. rta. We know that Himalayan ponies have always been brought southwards by salt traders and with them, of course, their names. There also is the independent and isolated Burushaski (in N. Pakistan) with ha-ghur, cf. Drav. gur- in Telugu guRRamu, Gondi gurram, etc., and the Austro-Asiatic Khasi (in Shillong) kulai, Amwi kurwa', etc., all of which again point to a northern origin. (For details see: EJVS 5-1, Aug. 1999, http://users.primushost.com/india/ejvs, or: International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics, 2001). Far from magically proving, with one Dravidian word, that the "native Indian horse" has been found in the South since times immemorial, the "man made theory" of linguistics --just as the hard facts of palaeontological science rather indicate that the words for `horse' were imported, along with the animal, from the (north)western (Iranian) and northern (Tibetan) areas. Genetics now add another facet. The domesticated horse seems to have several (steppe) maternal DNA lines (Science 291, 2001, 474-477; Science 291, 2001, 412; cf. Conservation Genetics 1, 2000, 341-355), which fits in very well with the several northern Eurasian words for it mentioned above. The Eastern Central Asian words must be added; they all probably derive from Proto-Altaic *mori (as in Mongolian morin, Chinese ma, Japanese uma, and as surprisingly also found in Irish marc, English mare). The Harappan "Sarasvati" The case of the Vedic Sarasvati river (the modern Sarsuti-Ghagghar-Hakra) is complex and cannot be dealt with in detail (see, rather, EJVS 7-3, section 25). It must be pointed out, however, that the Rigvedic Sarasvati is a river on earth, a `river' in the sky (Milky Way), and a goddess, and as such Sarasvati is described in superlative terms, once as flowing `from the mountains to the sea' (samudra). However, this word has several meanings that must be kept apart: `confluence, lake, mythical ocean surrounding the earth'; the sky, too, is called a `pond'! To commingle all of this as samudra `Indian Ocean' is bad philology. In addition, far from emptying into the Rann of Kutch then, the Harappan Sarasvati (`having lakes'), disappears as Hakra in the dunes around and beyond Ft. Derawar in Bahawalpur, after showing signs of a delta (playa) and of terminal lakes, just like its Iranian namesake in the Afghani desert, the Haraxvaiti (Helmand) with its Hamun lakes. Further, simple satellite photographs also do not show when a river dried up, as the Ghagghar-Hakra has indeed done several times in its different sections in recent millennia. This was shown in detail for the Indus and Vedic periods by the former director of Pakistani archaeology, Rafique Mughal, in his book Ancient Cholistan (1997). Rajaram again is simply wrong as a scientist in asserting that the river conveniently "dried up completely by 1900 BC." Reality is much more complex. Actually, much of this has been known since Oldham and Raverty (1886, 1892). (Thus, I myself have printed a Sarasvati map, based on a lecture of 1983, before the overquoted satellite photos of Yash Pal et al. were published in 1984). However, we need many more close observations such as Mughal's, with archaeologically vouched

dates for the individual settlements along the various sections and several courses of the river. Finally, the "oceanic descriptions" of the Rigveda imagined by Rajaram and many other rewriters of history (such as S.P. Gupta, Bh. Singh, D. Frawley) are based, again, on bad philology: their "data" are taken from Vedic mythology, floating in the night time sky, and the like! Or was Bhujyu abducted on another first, a Vedic airship? MICHAEL WITZEL Harvard University

The Hindu Open Page Tuesday, Mar 12, 2002 There is an urgent need to jettison from our textbooks the unproved statements on Indian civilisation and consign them to academic polemics, and keep the power mongering self-seeking Taliban politicians out of educational field.

THE READERS have been following closely the debate on Harappan civilisation, published in The Hindu in its Open Page. The latest article by Michael Witzel (March 5) seems to be taking a partisan view. Archaeologists have found certain artefacts and scholars are trying to infer the meaning of the findings and in the process express divergent views. Such debates are welcome to advance our knowledge academically, no matter where it comes from. Unfortunately, Witzel's present article reads personal rather than an academic presentation. For example, he ridicules the other writer N.S. Rajaram personally by repeating his name time and again, with personal digs in every mention. Witzel is not free from the same fault that he attributes to Rajaram, as in the example of horse in Harappan sites. He states the horse bones found in the early excavations at Mohenjodaro and Harappa do not come from secure levels, and such horse bones "found their way into deposits through erosion cutting and refilling, disturbing the archaeological layers." Neither does he say how he arrived at this conclusion nor has he cited any report in support of his view. What ever the case may be, it only shows that horse bones were actually found in the excavations at Harappan sites. In order to justify his stand he writes that Marshal's Harappan data are "dubious and decades old." One cannot throw away the data presented by Marshal as it is the earliest available archaeological report and it is not possible at this point of time to say suddenly that Marshal has not reported that layers that were eroded and disturbed in places where horse bones have been found. One may ask Witzel to state on what basis he says that the layers that yielded horse bones in more than one site as at Mohenjodaro and Harappa were eroded and disturbed and the bones got mixed up? Does he want us to believe that in both the sites, the same layers yielding horse bones got mixed up in eroded layers? There are

three major excavations conducted at Mohenjodaro and Harappa namely by Marshal, Mackey and Mortimer Wheeler. Reports of excavations George F Dales, who was the last in the series to investigate the sites, published his findings "Some unpublished, forgotten or misinterpreted features on Mohenjodaro" in the book Harappan Civilisation, published by the American Institute of Indian Studies, 1982. He has stated that the reports of all the three great excavations including that of Wheeler are "incomplete and suffer from serious losses." Dales states that there is "no end to speculation that these claims have aroused but it is impossible to reach objective conclusions with the published details." It is not at all possible to assess that the layers were disturbed unless other factual evidences are shown to approve the disturbed conditions. Michael Witzel also states that conclusions cannot be arrived at with incomplete bones. Yes. However there cannot be two sets of standards in dealing with the matter. For example, he questions the views of Rajaram, but does not show whether R. Meadow, whose conclusions he supports, based his views on "a full skeleton or full sets of onager, donkey, or horse skeletons." Further it is known that there are very rare examples where the full skeletons of animals have been found in excavations. Are we not aware that most of the reconstructions of dinosaurs are based not on full skeletons? Archaeologists reconstruct several cultures with broken pottery. At one place he admits that clear examples of horse bones are found in Harappan civilisation after 1800 BCE, which still falls in the late Harappan period. Witzel has a dig at archaeologists that they are not zoologists or palaeontologists to comment on animal bones. This would apply equally to Witzel who is not a trained archaeologist to comment on this science. No archaeologist is expert in all fields but certainly consults experts before expressing his comments on which he has no expertise. Problems are complex To sum up Witzel's arguments proceed on the following lines: (1) No horse bone has been found in Harappan sites. (2) When pointed out that they are found in some instances, it is said they are only fragments and not full skeletons. (3) When pointed out they were found in more than one site it is said the layers in which they were found ought to have been eroded ones or disturbed. (4) When pointed out that the reports of horse bones were not by present day archaeologists but by the early pioneers it is said that those are dubious and decades old. (5) When pointed out they were reported by archaeological excavators then comes the argument that archaeologists are not trained zoologists and palaeontologists to comment on horse bones (though by the same argument no credence can be placed on Witzel's opinion as he is neither an archaeologist nor a palaeontologist). Such arguments are brought under reductio ad absurdum by logicians. More examples of wilful rejections of points can be cited throughout the article but suffice to say that for an unbiased reader, the whole article reads purely a personal attack on an individual writer and exhibits certain amount of impatience to listen to other view. This does not mean that I agree with either of the views on the Aryan problem except stating that we are yet not in a position to go with either of the views for lack of evidence and would prefer to wait for further discoveries.

The debate has undoubtedly focused on one aspect of Harappan civilisation: the problems are complex and the data available are inadequate to come to any conclusion. The vital question that is not in the debate by the general reader is that in the past 50 years of India's independence, the unproved inferential views of these scholars, some of which have been proved totally wrong as in the case of "the total massacre of the Harappans by the invading barbaric Aryans", are fully incorporated in our school textbooks, right from the third or fourth standards. Wheeler dramatised this theory vehemently that invading Aryans destroyed the Harappan civilisation and within ten years he was proved totally wrong by new finds of several Harappan sites spread in space and time. And yet millions of children of India have been indoctrinated and brainwashed with these views for the past five decades, and that has caused immense damage to scientific knowledge. Is there any one party in India today which will repent for this incalculable damage? Are we justified in continuing to brainwash our generations of children? Is it not time that we remove these from school books and confine such debates to post-graduate community of the country and our children are told only the factual history. A perusal of the books would show enormous imbalances in representing regional and dynastic histories. It may be seen, for example, that South Indian history receives inadequate representation. The rule of the Pallavas, Cholas or Chalukyas that lasted for over four hundred years each and had glorious achievements in all fields gets summary representation, when compared with Mughal rule and the Colonial rule that did not last even half that period. South India has witnessed exemplary democratic institutions at the village level for several centuries in the medieval period that is yet to be brought to the notice of the children. Surely there is no proportionate representation. While the Western history gets exalted position in all fields, the history of South East Asia like Indonesia, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam and even China does not even get a cursory mention. There is clearly an urgent need to jettison from the books the unproved statements on Indian civilisation and consign them to academic polemics, keep the power-mongering self-seeking Taliban politicians out of educational field, and seek a proportionate place for Indian civilisation in our textbooks. In fact Witzel has agreed to the need to revise Indian history in his earlier article, which should be entrusted to a body of unbiased and balanced academic body free from racial, religious or political bias. R. NAGASWAMY

Former Director of Archaeology, Tamil Nadu

The Hindu Open Page Tuesday, May 21, 2002 Horses, logic and evidence MICHAEL WITZEL We can certainly agree to rewrite sections of ancient Indian history, but this has to be done on the basis of new facts, not of new myths or of incomplete archaeological or zoological data. It is the duty of scholars to point out such new myths before they enter the new textbooks.

The recent discussions (Open Page, January-March 2002) on the supposed total overlap, or rather, the incidental connections between the Harappan (Indus) Civilisation and the Vedic texts have been submerged by current political events. However, one grand claim follows another with regard to India's ancient past, and these are frequently supported by certain politicians. This ranges from the Gulf of Cambay finds (where one piece of wood, found in swift currents, is used to date the site to 7500 BCE!) to the usefulness of the study of astrology, now introduced at many universities. Most recently, the Ministry of Defence has approved a study of India's Machiavelli (Kautilya's Arthas'aastra, a multi-layered text of c. 300 BCE to 100 CE) for matters of conventional, biological and chemical warfare. In this intellectual climate it is not futile to add my notes of late March on the Harappan/Vedic question (see http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/witzel/Harveda.htm), now slightly updated. Rewriting craze This certainly is not the end of the important discussion of the current ethnocentric "rewriting" craze, a phenomenon that has begun already with the "reinterpretation" of Vedic texts by Dayanand Sarasvati in the 19th century (s'veta dhuuma `white smoke' = locomotive). Indeed, the phenomenon should be studied in much more detail, and also comparatively, by drawing in similar developments in other cultures, Asian (http://www.umass.edu/wsp/methodology/antiquity/index.html), or other. However, to conclude the interrupted discussion on imaginary Indus horses, I resubmit the following contribution. The vexed question of the `Harappan horse' does not seem to go away. I am glad to see that my last paper in Open Page (March 5, 2002) has elicited a strong reaction, this time (March 12) from a professional archaeologist, R. Nagaswamy, the former Director of Archaeology, Tamil Nadu. He has narrowed down the long debate about the Indus and Vedic civilisations to the question of horses in the archaeological record, about which more below. To begin with, Nagaswamy and I certainly agree about the need of `rewriting' ancient Indian history from time to time. This is a normal procedure in historiography when new data have been discovered that result in the need for new interpretations.

I also agree that this "should be entrusted to an unbiased and balanced academic body free from racial, religious or political bias" as well as to individual, well prepared scholars who can contribute their insights. Certainly, we can also agree that "South Indian history has received inadequate representation" so far. However, it will be difficult to "confine such debates to post-graduate community of the country and our children are told only the factual history." What is factual history? And how does one decide this? Obviously, interpretation of various types of data is involved here, and the results of such discussions printed in history books will be based on extensive debate and a certain amount of scholarly consensus. Interpretations We both would also agree that such interpretations should not be long discarded ones, e.g., those of M. Wheeler ("Indra stands accused" referring to the destruction of the Indus cities). However, they should also not be such as the recent fantasies of N.S. Rajaram (et al.), whose "decipherment" of the Indus script and all interpretations that flow from this are a priori wrong because he uses the wrong direction of the script, a direction that was securely established decades ago by the former Dir. Gen. of Archaeology, B.B. Lal (see I. Mahadevan, at the Indian History Congress, Dec. 2001, and in EJVS 8-1, http://users.primushost.com/india/ejvs/issues.html). "Digs" at the writings of persons such as Rajaram thus have their well-justified reasons. Especially so, as he had recently been appointed by the Minister of HRD as a member of the ICHR, a position he turned down after strong disapproval in the Indian press. Such appointments spell the end of scientific history writing and open the door to Raamraaj fantasies galore. Second, there is the vexed question of the "Harappan horse". Though merely being a philologist and something of a linguist, I have read the relevant scientific literature, and I have additionally asked some scientist colleagues, just to be 100 per cent sure. For my last piece in Open Page I consulted archaeologists and archaeozoologists, upon whose advice I have changed two or three sentences. I showed my piece, for example, to my colleague at Harvard, R. Meadow. He is both an archaeologist and an archaeozoologist (one who studies animal bones from archaeological sites). In addition, he happens to be a Director of the Harappa Archaeological Research Project, where he has been digging for more than a decade; he also knows first hand many other early sites, e.g., Mehrgarh and Pirak in Baluchistan. Amusingly, it is exactly the very sentence that the archaeologist Nagaswamy criticised that I changed based on input from the Harappan archaeologist R. Meadow, namely that horse bones are likely to have "found their way into deposits through erosion cutting and refilling, disturbing the archaeological layers." Nagaswamy complains that "neither does he say how he arrived at this conclusion nor has he cited any report in support of his view." Unfortunately my references for this were cut by editors; here are the details: R. Meadow in: The Review of Archaeology, 19, 1998, 12-21; R. Meadow in: D.R. Harris (ed.) The Origins and Spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia.1996, 390-41. UCL Press, London; R. Meadow and A. Patel in: South Asian Studies,13, 1997, 308-315. Here for Nagawamy then are the references to the still elusive "Harappan horse." If Nagaswamy had read such relevant technical literature himself he would have seen why the archaeozoological situation is as bad as I described it. But since he has

not, he perfectly exemplifies the case I made, namely that archaeologists do not necessarily know enough of archaeozoology, and their judgments thereof can be flawed. For example, the volume edited by G.M. Pande, The Dawn of Indian Civilisation (Delhi 1999) mentions many times just "horses," without any further specification of equid type or any discussion. But, this kind of statement is believed at face value, as I have seen, by both the general and scholarly public. Unfortunately Nagaswamy has also not checked the archaeological sources well enough. When he says that "there are three major excavations conducted at Mohenjodaro and Harappa namely by Marshal, Mackey and Mortimer Wheeler... George F. Dales, who was the last in the series to investigate the sites..." (1982), apart from contradicting himself within a few words, he simply overlooks decades of excavations at Harappa (and elsewhere!), excavations that have been reported in archaeological publications and even in a recent generally available synthesis by J. M. Kenoyer, Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilisation, Oxford University Press 1998. All of this should perhaps not surprise. As far as I can see, R. Nagaswamy has proficiently published on Tamil literature, culture, and archaeology, including even one excavation report (about Vasavasamudram), written together with Abdul Masjeed in 1978. This lacuna may be the reason why he resorts to a discussion of "logic" instead. However, the evaluation of archaeological/archaeozoological detail cannot be reduced to "logic" by comparing various sentences from my paper, as he does: "Such arguments are brought under reductio ad absurdum by logicians". Instead, to state it clearly one more time: what we need is absolute security (to the degree scientifically possible) with regard to identification of the bones themselves, radiocarbon dates directly on the bones in question, and a detailed understanding of the archaeological context from which they come. It is evidence that counts, not a "logic game". Nagaswamy even distils from my paper that "it only shows that horse bones were actually found in the excavations at Harappan sites." But, this is precisely what was and still is under discussion! Even if we accept the identifications as true horse of material from the old excavations (and this still needs to be rechecked by specialists using the original material), we lack the other two pieces of information context and direct date that are necessary to securely interpret the cultural meaning of those identifications. Context and stratification As scholars know, archaeology just as palaeontology (or linguistics) is all about location, context, and stratification. An isolated horse skeleton, complete or not, just shows that a horse was present in that location at some time in the past. As an example, a nearly complete camel bone (humerus) was found at Harappa about a metre below the surface together with artifactual remains that could be assigned by archaeologists to the last part of the "mature" Harappan period (ca. 2200-1900 BC). A direct radiocarbon date on the bone itself, however, came out to be 690 CE, more than two thousand years later (Meadow 1996 & 1998): a clear case of a deposit effected "through erosion cutting and refilling." If, in addition, that find is not recorded in detail and actually reported in print (a common lack in Indian archaeology of the past few decades, as recently bemoaned by officials and in the press a few weeks ago) it is almost worthless just as in linguistics a modern

Sanskrit word like kendra "centre" could go back to a formation based on the modern English `centre' or could be derived from a Greek word (kentron), which is the case, as it is already attested by Varahamihira at 550 CE. The levels are clear here. But bones from old and not well recorded excavations (Nagaswamy himself quotes some doubts in Dales' review of Indus excavations!), bones that in addition have not been radiocarbon dated and may not have been correctly identified through comparison with modern specimens, just do not provide suitable evidence. The alleged find of a horse or camel bone at Harappa without details of the identification, the context, and a direct date then is open to question: yesterday's Afghan or Sikh sipahi's half-horse can be turned into tomorrow's full Harappan horse... In sum, in the sciences we cannot work with data that do not conform to strict procedures and methods, such as those delineated above. Third, as for the discussion of various equids (true horse, ass, half-ass/onager), Nagaswamy complains that I do "not show whether R. Meadow ... based his views on a full skeleton or full sets of onager, donkey, or horse skeletons." Again Meadow (and I, quoting him) has explained fully in his 1996-1998 papers why such detailed comparison is necessary, and that good collections of modern specimens, necessary to compare such finds, are only just now being established in South Asia itself. Fourth, when true horses are indeed found, finally, in the Kachi Plain of East Baluchistan (part of the Indus Valley) at c. 1800 BCE, this does not make them Harappan, as Nagaswamy maintains: "...1800 BCE, which still falls in the late Harappan period". A study of the Pirak data would show that these sites are postmature-Harappan and have a very different material culture inventory than the earlier Harappan sites in the same area. To lump all cultures from 3500 to 1500 BCE together as "Harappan" (or even as "Sarasvati" well before its actual first naming in Sanskrit!) is not correct, and opens the door to all sorts of unscholarly rewritings of ancient history, in other words, to new myth making. In sum, in my recent Open Page article, I intentionally preferred to err on the side of caution: Advised by specialists, I specified the conditions that are necessary to identify horses, and I did not simply follow the conclusions of various writers as to the nature of one set of bones or the other. To repeat it one final time: we need the bones in contention (1) to come from well stratified deposits the formation of which is understood, (2) to be carefully identified with the reasons for their identification published in detail, and (3) to be directly radiocarbon dated if possible. At the present time, these conditions have not been met well, and all conclusions must be explicitly preliminary or else they can only be called speculative or misleading. If this stance is called "taking a partisan view", then I may gladly be called partisan. This certainly is better than to find, with Rajaram et al., horses (or "fire altars") all over the early subcontinent (see Frontline, Oct./Nov. 2000). Such writers see horses everywhere. To sum it up once more, we can certainly agree to rewrite sections of ancient Indian history, but this has to be done on the basis of new facts, not of new myths or of incomplete archaeological or zoological data. It is the duty of scholars to point out such new myths before they enter the new textbooks. MICHAEL WITZEL (assisted by Richard Meadow) Harvard University

The Hindu Open Page Tuesday, Jun 18, 2002 Vedic literature and the Gulf of Cambay discovery It is sad to note how intellectuals in India are quick to denigrate the extent and antiquity of their history, even when geological evidence like the Sarasvati River or archaeological evidence like the Harappan and Cambay sites are so clear.