Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Dying Forests Package, Page 2

Enviado por

The Salt Lake TribuneTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Dying Forests Package, Page 2

Enviado por

The Salt Lake TribuneDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

F 2 > O U R D Y I N G F O R E S T S S U N D A Y , S E P T E M B E R 25, 2011

A forest under siege Whitebark pines, like these near Jackson Hole, are dying so rapidly that they qualify as an endangered species. But government cannot afford to fully protect them.

THE SALT LAKE TRIBUNE

Warming winters have allowed waves of beetles to gnaw their way through millions of acres of forests in Utah and across the West.

The Salt Lake Tribune

Fading to gray

which has swept through neighboring ranges almost since he settled here in 1994. They say theyre working on it, DuChane sneered, remembering his pleas with Gallatin National Forest rangers. Its the government. It aint doing anything. His is a complaint echoed by Western politicians, who think government land managers heaped disaster on the region by letting forests grow so thick that the trees cannot get enough water and sunlight to defend themselves from the pests. But what if something larger than the federal bureaucracy is at work? What if the real culprit isnt a faltering Uncle Sam but a changing Mother Nature? A rogue wave of insects riding on a decade of drought and ever-warmer winters is now cresting here, where DuChane believes his perch is threatened: the elk he hunts, the view and the trout that brought him west from Wisconsin, and, in case of re, even the home he built for himself. You wont see this in my lifetime, DuChane said, tilting his cowboy hat at the few patches of green that remain but will fade by next summer. The replacement trees, if they grow, will take a century to mature. Its gone. Americas alpine climate has changed dramatically in recent decades, warming enough for university and government researchers to state atly that nothing will ever be the same. Not the widely spaced natural cycle of beetle kills. Not the small fires that routinely thinned and rejuvenated forests. Not the trees themselves, which may shift to new species better adapted to a changing habitat. Across the continents spine, the forests that dened the Marlboro Mans high West are dead, dying or so choked with combustible life that they inspire more fear than wonder. High-elevation trees that shade and anchor snowbanks through spring are most susceptible, perhaps leading to earlier runoff, greater flooding and dirtier rivers. A millennium-spanning species whose pine nuts fatten Yellowstone grizzlies is startlingly on the brink, bug-struck and sun-bleached into alpine skeletons of incomprehensible body counts. Mountain pine beetles are flying in new territories previously thought too cold, such as northern British Columbia or just under the thinair crags of western Wyomings Tetons. Utahs dominant tree of commercial value, the Engelmann spruce, is under attack and, by Forest Service estimates, may survive only in the High Uintas by centurys end. ive years ago, Jesse Logan retired to Paradise Valley, a 20-minute drive north of Yellowstone, after leading the Forest Services bark-beetle studies. He wanted to sh and ski, but he also keeps busy documenting the loss of old trees on nearby mountaintops the ones he likes to ski between and the ones that regulate water ows and temperatures by holding snow into summer. Without them, the native cutthroat trout he stalks will suffer. These forests are enchanting places, Logan said. [Yellowstone] just captured my imagination and my heart,

By BRANDON LOOMIS

Bozeman Pass, Mont. A gray-whiskered former flyshing guide waded through a horse pasture whacking weeds for his neighbor, the rumbling machine in his hands slicing thistles and sparing a robust tangle of grass and wildflowers, while on mountain ridges all around him, the trees silently died. Beetles. Here, along the pine-scented exurban glory of Trail Creek, Lester DuChane and his sparse neighbors are the latest Westerners to watch their green valley turn red and fade to gray as swarms of rice-grain-size beetles eat the Rocky Mountain forest. He cannot figure out why the government never launched an aggressive counterattack against an epidemic,

Ring masters chart climate change Reporter Judy Fahys tells how tree rings tell the tale of our warming climate. > sltrib. com. See more photos and video More photo galleries, stories and video about the state of our forests. > sltrib.com. Interviews with experts in the eld Watch the video that accompanies this story at bit.ly/killingforests or scan this QR code with your mobile device.

F

Tree Fight volunteers march through a meadow in early August searching for surviving whitebark pine above Togwotee Pass, Wyo. They will attach chemical patches to protect the trees.

BRANDON LOOMIS | The Salt Lake Tribune

and it breaks my heart to see whats happening in these high-elevation, old-growth forests. Part of foresters diagnosis reflects a cold reckoning of facts known for a generation: A century of Smokey Bear fire suppression and decades of timber-industry decline primed thick forests for giant blazes and for drought stress, which invites tree-killing insects. The other part is new: Warming winters and longer growing seasons have ignited a 14-year beetle explosion like none ever documented. Brighton Ski Resort southeast of Salt Lake City, topping out at 10,500 feet, has warmed its average nightly winter lows by more than 5 degrees Fahrenheit over four decades, according to the Utah Climate Center at Utah State University. It doesnt feel so different through puffy gloves when youre skiing under the lights, but it represents fewer bugkilling deep freezes. Mountain pine beetles have sapped acres of the gnarly old limber pine that defined the ridge, a sad thing because some of those are hundreds of years old, ski area Manager Randy Doyle said. Employees have tacked synthetic anti-beetle pheromones on the remaining 200 or so limber pines. Spruce beetles spilling over the crest from American Fork Canyon form a second front at Brighton, forcing the resort to selectively cut pockmarked spruce a couple of hundred last year in hopes of removing the insects before the next generation emerges. Unlike pine beetles, spruce beetles so far have evaded efforts to produce a synthetic pheromone repellent. Brighton plants and shelters seedlings for the next generation, hoping for a hospitable landscape. Since 1997, a host of native beetle species has chewed through more than 40 million acres of Western forests,

Você também pode gostar

- Upper Basin Alternative, March 2024Documento5 páginasUpper Basin Alternative, March 2024The Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- Teena Horlacher LienDocumento3 páginasTeena Horlacher LienThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- Salt Lake City Council text messagesDocumento25 páginasSalt Lake City Council text messagesThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- Richter Et Al 2024 CRB Water BudgetDocumento12 páginasRichter Et Al 2024 CRB Water BudgetThe Salt Lake Tribune100% (4)

- Goodly-Jazz ContractDocumento7 páginasGoodly-Jazz ContractThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- Unlawful Detainer ComplaintDocumento81 páginasUnlawful Detainer ComplaintThe Salt Lake Tribune100% (1)

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers LetterDocumento3 páginasU.S. Army Corps of Engineers LetterThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- NetChoice V Reyes Official ComplaintDocumento58 páginasNetChoice V Reyes Official ComplaintThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- Park City ComplaintDocumento18 páginasPark City ComplaintThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- Opinion Issued 8-Aug-23 by 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in James Huntsman v. LDS ChurchDocumento41 páginasOpinion Issued 8-Aug-23 by 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in James Huntsman v. LDS ChurchThe Salt Lake Tribune100% (2)

- Settlement Agreement Deseret Power Water RightsDocumento9 páginasSettlement Agreement Deseret Power Water RightsThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- Wasatch IT-Jazz ContractDocumento11 páginasWasatch IT-Jazz ContractThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints Petition For Rehearing in James Huntsman's Fraud CaseDocumento66 páginasThe Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints Petition For Rehearing in James Huntsman's Fraud CaseThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- Spectrum Academy Reform AgreementDocumento10 páginasSpectrum Academy Reform AgreementThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- Gov. Cox Declares Day of Prayer and ThanksgivingDocumento1 páginaGov. Cox Declares Day of Prayer and ThanksgivingThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- Superintendent ContractsDocumento21 páginasSuperintendent ContractsThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- David Nielsen - Memo To US Senate Finance Committee, 01-31-23Documento90 páginasDavid Nielsen - Memo To US Senate Finance Committee, 01-31-23The Salt Lake Tribune100% (1)

- Employment Contract - Liz Grant July 2023 To June 2025 SignedDocumento7 páginasEmployment Contract - Liz Grant July 2023 To June 2025 SignedThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- US Magnesium Canal Continuation SPK-2008-01773 Comments 9SEPT2022Documento5 páginasUS Magnesium Canal Continuation SPK-2008-01773 Comments 9SEPT2022The Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- PLPCO Letter Supporting US MagDocumento3 páginasPLPCO Letter Supporting US MagThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- HB 499 Utah County COG LetterDocumento1 páginaHB 499 Utah County COG LetterThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- 2023.03.28 Emery County GOP Censure ProposalDocumento1 página2023.03.28 Emery County GOP Censure ProposalThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- SEC Cease-And-Desist OrderDocumento9 páginasSEC Cease-And-Desist OrderThe Salt Lake Tribune100% (1)

- US Magnesium Canal Continuation SPK-2008-01773 Comments 9SEPT2022Documento5 páginasUS Magnesium Canal Continuation SPK-2008-01773 Comments 9SEPT2022The Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- Final Signed Republican Governance Group Leadership LetterDocumento3 páginasFinal Signed Republican Governance Group Leadership LetterThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- US Magnesium Canal Continuation SPK-2008-01773 Comments 9SEPT2022Documento5 páginasUS Magnesium Canal Continuation SPK-2008-01773 Comments 9SEPT2022The Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

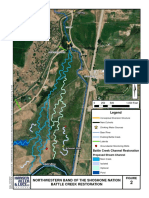

- EWRP-035 TheNorthwesternBandoftheShoshoneNation Site MapDocumento1 páginaEWRP-035 TheNorthwesternBandoftheShoshoneNation Site MapThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- Utah Senators Encourage Gov. DeSantis To Run For U.S. PresidentDocumento3 páginasUtah Senators Encourage Gov. DeSantis To Run For U.S. PresidentThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- Ruling On Motion To Dismiss Utah Gerrymandering LawsuitDocumento61 páginasRuling On Motion To Dismiss Utah Gerrymandering LawsuitThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- Proc 2022-01 FinalDocumento2 páginasProc 2022-01 FinalThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Gis Sols For AgricultureDocumento8 páginasGis Sols For Agriculturethirumangai6100% (1)

- NE VisionDocumento633 páginasNE VisionAyush BidawatkaAinda não há avaliações

- Bolivian Food Primer: 10 Essential Dishes and DrinksDocumento9 páginasBolivian Food Primer: 10 Essential Dishes and DrinksMario Zárate FabiánAinda não há avaliações

- Short Course BrochureDocumento2 páginasShort Course Brochuresrija.kAinda não há avaliações

- Pruning and training apple treesDocumento9 páginasPruning and training apple treesgheorghiud100% (1)

- PosterDocumento1 páginaPosterWartono TonoAinda não há avaliações

- Afa M1L2Documento24 páginasAfa M1L2Hb HbAinda não há avaliações

- 2002 Comprehensive Rules On Land Use ConversionDocumento7 páginas2002 Comprehensive Rules On Land Use ConversionKuthe Ig TootsAinda não há avaliações

- Development and Testing of Solar Operated Paddy WinnowerDocumento3 páginasDevelopment and Testing of Solar Operated Paddy WinnowerAbdullahi Abdul-semi'i AderojuAinda não há avaliações

- Restaurant dialogue and food quizDocumento3 páginasRestaurant dialogue and food quizDonny HermawanAinda não há avaliações

- Coperative Management Ritesh and GroupDocumento22 páginasCoperative Management Ritesh and GrouppankajkubadiyaAinda não há avaliações

- Red MapleDocumento2 páginasRed MapleTakako Kobame KobayashiAinda não há avaliações

- Sheep Farms in AragonDocumento17 páginasSheep Farms in Aragonnpotocnjak815Ainda não há avaliações

- Excavation ProcedureDocumento3 páginasExcavation Proceduresudarsancivil100% (1)

- NestleDocumento5 páginasNestleEllaine MorenoAinda não há avaliações

- Man Who Guarded Franklin Roosevelt Lived in Zumbrota: Two From The Area Are State ChampsDocumento14 páginasMan Who Guarded Franklin Roosevelt Lived in Zumbrota: Two From The Area Are State ChampsKristina HicksAinda não há avaliações

- Glycemic Index Food ListDocumento12 páginasGlycemic Index Food Listparacelsus5Ainda não há avaliações

- The Kitchen Herb Garden - A Seasonal Guide To Growing, Cooking and Using Culinary Herbs PDFDocumento248 páginasThe Kitchen Herb Garden - A Seasonal Guide To Growing, Cooking and Using Culinary Herbs PDFsdpml100% (2)

- Chitosan Application in Maize (Zea Mays) To Counteract The Effects of Abiotic Stress at Seedling LevelDocumento8 páginasChitosan Application in Maize (Zea Mays) To Counteract The Effects of Abiotic Stress at Seedling LevelRamadi WiditaAinda não há avaliações

- Bombay Deccan and KarnatakDocumento245 páginasBombay Deccan and KarnatakAbhilash MalayilAinda não há avaliações

- Post Office MuralsDocumento35 páginasPost Office MuralsnextSTL.comAinda não há avaliações

- Report QuailDocumento15 páginasReport Quailpoppye1942Ainda não há avaliações

- Soil Genesis Survey and ClassificationDocumento13 páginasSoil Genesis Survey and ClassificationrameshAinda não há avaliações

- AdlaiDocumento2 páginasAdlaiJoresel Coronado100% (5)

- Economics Class 11 Unit 7-AgricultureDocumento0 páginaEconomics Class 11 Unit 7-Agriculturewww.bhawesh.com.np0% (1)

- 5 OdishaDocumento21 páginas5 OdishaGAinda não há avaliações

- Historical Places & Tourist Spots of Davao RegionDocumento7 páginasHistorical Places & Tourist Spots of Davao RegionJp DescAinda não há avaliações

- 2808 Bcs XG Slugs 2012 v5 PDFDocumento26 páginas2808 Bcs XG Slugs 2012 v5 PDFDare SpartuAinda não há avaliações

- Model Based Yield Gap Analysis and Constraints of Rainfed Sorghum Production in Southwest EthiopiaDocumento15 páginasModel Based Yield Gap Analysis and Constraints of Rainfed Sorghum Production in Southwest EthiopiaEndale AmdekiristosAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment 1-Why The Mechanization Endevour Has Not Been A Smooth One For KenyaDocumento4 páginasAssignment 1-Why The Mechanization Endevour Has Not Been A Smooth One For KenyaBRUCE OYUGIAinda não há avaliações