Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

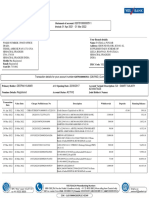

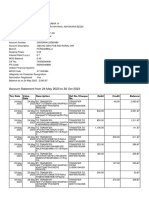

Banking Sector

Enviado por

Harsha Vardhan KambamDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Banking Sector

Enviado por

Harsha Vardhan KambamDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

http://www.businessandeconomy.org/10112011/storyd.asp?

sid=6489&pageno=5

Are Indian Banks Ready for Crisis Part II?

At a time when the global economy is heading towards another financial crisis, perhaps even worse than the one that hit the world in 2008, Indian banks are grappling with issues like moderating credit growth, rising slippage ratio and mounting credit cost. can they weather the rising storm?

Issue Date - 10/11/2011

Indian banks, the dominant financial intermediaries in the country, have evolved dramatically over the last few years. And it is evident from several parameters, including credit growth, profit margins, and trend in gross non-performing assets (NPAs). While the annual rate of credit growth clocked 23% during the last five years, profitability (average return on net worth) was maintained at around 15% during the same period. Even gross NPAs fell from 3.3% as on March 31, 2006 to 2.3% as on March 31, 2011. Good internal capital generation, reasonably active capital markets, and governmental support also locked up better capitalization for most banks during the period, with overall capital adequacy touching 14% as on March 31, 2011. At the same time, high levels of public deposits ensured that most banks had a comfortable liquidity profile, so much so that they even weathered the 2008 global financial comfortably. So far, so good. But, at a time when the US is grappling with serious debt issues (US public debt stands at a whopping $14.618 trillion, about 103% of its GDP), and the nations in the Eurozone are bowing to sovereign debt crisis, one by one (first Ireland, then Greece and Portugal), can Indian banks remain afloat? What about factors like moderating credit growth, rising slippage ratio and mounting credit costs? Arent these enough to derail the Indian banking system and place it alongside its European counterparts that are finding it hard to stay grounded in an environment which is perhaps even worse than that of 2008, courtesy the sovereign debt crisis? For the uninitiated, the Indian financial sector (including banks, non-banking financial companies, or NBFCs, and housing finance companies, or HFCs) reported a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 19% over the last three years and their credit portfolio stood at close to Rs.49 trillion (around 62% of FY2010-11 GDP) as on March 31, 2011. While NBFCs accounted for about 10% of the total credit, and HFCs for around 4%, those were banks that dominated the scene accounting for nearly 86% of the total credit. In fact, total banking credit stood at close to Rs.39 trillion as on March 31, 2011 and reported a strong 21.4% growth in FY2010-11, led by credit to the infrastructure sector and to NBFCs. But, as the global environment turns grim and the Indian economy too starts feeling the pinch (Indias real GDP moderated for the third consecutive quarter, rising 7.7% yoy in Q2 2011, down from a 7.8% yoy rise in Q1 2011), Indias so-far-insulated banking system is about to face several challenges in the near future, which include increase in interest rates on saving deposits, a tighter monetary policy, a large government deficit and implementation of Basel III norms. In fact, the deceleration of the Indian economy in the context of the global financial turmoil and an increasingly bleak economic outlook coupled with rising delinquency rates (number of past-due loans divided by the total number of current loans), has highlighted the potential for a weakening in the asset quality of Indian banks.

The biggest problem is that with higher interest rates, companies, particularly SMEs, and individuals are finding it difficult to repay loan installments. This adds to the bad loans or nonperforming assets (NPAs) of lenders. In fact, this is exactly what Moodys, a global rating agency, had cited as the reason when it recently downgraded Indias leading lender State Bank of Indias (SBI) rating by one notch to D+ from C- (as per Moodys definition, banks rated C have adequate intrinsic financial strength, while those rated D have modest intrinsic financial strength, potentially requiring some outside support at times). According to Moodys Investors Service, non-performing loans at SBI rose to a three-year high of 3.5% ($5.6 billion on an absolute basis) in June 2011. Even worse, NPA as a percentage of the banks Tier 1 capital (SBI reported a Tier 1 capital ratio of 7.60% as of June 30, 2011 against 8% Tier 1 ratio that the government has committed to maintain in PSBs) is now about 43%. Although other banks seem to be in a better position than SBI in India, the situation is not really good when one compares them with their Asian counterparts. As per Moodys, for all Indian financial institutions NPAs as a percentage of total assets stand at around 2.3% at present, relatively higher when compared with Chinese, Taiwanese and Australian banks, which have nonperforming loans estimated at around 2% of total lending.

Further, the spill-over from restructuring window, which RBI opened in FY2008-09, is not over yet. To recall, in December 2008, the RBI had allowed a second time restructuring of corporate advances and a one-time restructuring of commercial real estate advances. As part of this exercise, banks had allowed deferment of principal repayment to eligible borrowers by 6-12 months. And its because of this process that the restructured advances accounted for about 4% of scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) total advances as on March 31, 2011.

In fact, for PSBs, restructured advances were higher at 4.5% in March 2011 because of their higher lending to the corporate sector, while for private banks, such advances were lower at around 1% of their credit portfolio. Interestingly, while some of these restructured accounts have already slipped into the NPA category over the last two years (in the range of 820% for various banks), with the operating environment further deteriorating, the slippages from restructured advances could continue into FY2011-12 as well. Agrees Matthew Circosta, the Sydney based Economist at Moodys Analytics, as he tells B&E, Bad loans bear watching because they could lead to bank failure and ultimately a credit crunch. However, he is quick enough to add that such loans still represent only a small share of lending in India and across Asia. But then, not to forget, every big fire starts with a small spark!

Even IDBI Capital, the investment banking and securities arm of IDBI Bank, factors a stress case assumption of 25% increase in restructured assets and 15% delinquencies from those restructured assets apart from high normal slippages going forward. This is above the historical trend of 80-85% success in restructured assets and 10-15% slippage in those restructured assets. And the bad news doesnt end here. After factoring in increases in slippages ratio, credit cost and reduced margins, IDBI Capital estimates 11.7% CAGR in profit after tax (PAT) for PSBs and 15.3% CAGR in private sector banks during FY2011-13, the lowest over the last 5 years.

Apart from rising slippages, exposure to state utilities remains an area of concern for Indian banks. In fact, the exposure of banks to the power sector has increased from Rs.602 billion as in March 2006 (around 4% of total banking credit) to Rs.2,692 billion as in March 2011 (around 7% of total banking credit). Banking credit to the power sector as a percentage of banks total net worth has also increased from 33% in March 2006 to 56% in March 2011. And within these, loans given to fund the cash losses of state utilities are estimated at 30-40% of the total power-sector exposures. Since the financial health of state power utilities remains poor, it is likely that they will find it difficult to service debt on time, and this could be a problem for banks unless power sector reforms gain pace.

No doubt, to absorb any shocks from rising bad loans, the government is providing financial support to banks. For instance, during FY2010-11, the government had infused Rs.165 billion in PSBs to improve their Tier 1 capital to 8% and take up its stake in the PSBs to at least 58%. After this, the Tier 1 capital of most of the PSBs has improved. Therefore, these banks (apart from SBI) may not require significant Tier 1 capital in the short term. In case they do, the government has budgeted for Rs.60 billion for them in FY2011-12. But then, how long can PSBs rely on continued government support given the countrys large government debt burden (Indias budget deficit could widen to 5.8% of GDP in FY2012 as against the government target of 4.8%)? They definitely need to set aside more cash to ensure that bad loans dont grow; i.e. they are in a position to write off bad loans as and when required. As far as private banks are concerned, they seem to be well capitalized to meet the medium term needs, although some may need equity to fund their growth plans. At an aggregate level, Indian banks fare well against the Basel III requirement for capital too. However, some may appear inferior on comparison. For instance, nine banks had Tier 1 capital of less than 8.5% as on March 31, 2011. Considering the stricter deductions from Tier 1 and the fact that some of the existing perpetual debt (around Rs.250 billion) would become ineligible for inclusion under Tier 1, some banks may need to infuse core capital (equity capital) in the near future. Additional capital may also be required to support a growth rate that exceeds the internal capital generation rate, which is likely.

Another factor that might further erode the profitability of Indian banks in the near future is the rising cost of deposits. The reason is simple. In recent periods, the spread between the savings bank (SB) deposit and term deposit rates has widened significantly. This is thanks to RBI, which in May 2011, raised the SB deposit interest rate from 3.5% to 4.0%. At the systemic level, SB deposits are estimated to account for 22-23% of total bank deposits (as of March 31, 2011). Thus, even a slight increase of 0.5% in interest rate on SB deposits could raise the cost of deposits by around 13 basis points (bps) at the systemic level. If banks do not pass on this additional cost to borrowers, their net interest margins (NIMs) could be diluted by 10 bps. This translates into a dent of 100 bps on the return on equity. In fact, the impact would be higher for banks with a large proportion of SB deposits (for example SBI, Punjab National Bank, ICICI Bank and HDFC Bank) than for those with a smaller share of such deposits (which includes UCO Bank, Oriental Bank of Commerce). Overall, the impact on NIMs for various banks ranges from 5 to 15 bps, which even if not very significant per se, would certainly add to the pressures on profitability of banks.

So, whats the way out? As far as the immediate measures are concerned, the only thing that Indian banks need to ensure is that they have adequate capital to support short term growth. Although a temporary slack in credit growth and adjustment in the lending rate may lead to a dip in the NIM of Indian banks in the first half of FY2011-12, the situation is likely to recover in H2 FY2011-12 (depending on the credit off-take). Overall, the Indian banks continue to enjoy a comfortable capitalisation, as per the existing RBI norms (8%), with their Tier 1 capital close to 9% (this even fulfills the Basel III requirement of Tier 1 capital at 8.5%) and, apart from a few, none of them may need significant Tier I capital in the short term. However, if the Indian banking industry wants to sustain itself in the long run, a coordinated effort between the various entities is certainly required to enable positive action. This will not only stimulate the performance of the sector, but will also make the Indian banking sector immune to global financial crisis, which happens to be an imminent danger at present. In fact, the policymakers need to shape a superior industry structure in a phased manner through managed consolidation and by enabling capital availability. This would create 4-5 global sized banks controlling 40-45% of the market in India; 7-8 national banks controlling 25-30% of the market; 4-6 foreign banks with 15-20% share in the market. Interestingly, at present the average asset size of commercial banks in India stands at $0.77 billion (average of total assets of 81 scheduled commercial banks and 82 regional rural banks at present conversion rate), as compared to an average assets size of $1.93 billion for all commercial banks in the US (6,413). For that matter, even the biggest of the Indian banks are quite small on a global platform. For instance, the size of largest bank of China Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) is five times the size of the entity formed by combining five largest banks of India. Thus, consolidation is unavoidable if Indian banks are to become a force to reckon with in the near future. Last but not least, policymakers certainly need to create a unified regulator for the industry, distinct from the central bank of the country, in a phased manner. This will not only help the industry as well as policymakers to overcome supervisory difficulties, but will also reduce compliance costs. To conclude, despite the expected increase in slippages in the short term, the Indian banks (barring a few) are well-equipped with a good overall solvency profile and a comfortable provision cover to absorb any shocks in the near term. In fact, the ongoing global crisis may fast-track long-pending banking reforms, which are, in any case, critical to sustaining the long-term growth, not only of the industry, but also of the Indian economy.

Você também pode gostar

- BSE Sensex Status: World IndicesDocumento28 páginasBSE Sensex Status: World IndicesHirendra PatilAinda não há avaliações

- All India Mobile SeriesDocumento12 páginasAll India Mobile Seriesajitkumar150% (2)

- 01 Apr 2021 - 31 Mar 2022Documento27 páginas01 Apr 2021 - 31 Mar 2022Deepak KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Gurgaon CorporatesDocumento27 páginasGurgaon CorporatesKautilya KalyanAinda não há avaliações

- Corporate Database22Documento126 páginasCorporate Database22Dhiren PatilAinda não há avaliações

- Management Entrepreneurship and Development Notes 15ES51Documento142 páginasManagement Entrepreneurship and Development Notes 15ES51Amogha b94% (18)

- Navi Mumbai MidcDocumento214 páginasNavi Mumbai MidcVishal Salve72% (32)

- BC Details UK DistrictDocumento3 páginasBC Details UK DistrictNisa ArunAinda não há avaliações

- NonPerforming Assets of Indian BanksDocumento3 páginasNonPerforming Assets of Indian BanksselvamuthukumarAinda não há avaliações

- Dilemma of Indian BankingDocumento7 páginasDilemma of Indian BankingAnubhav JainAinda não há avaliações

- Macro-Economics Assignment: Npa of Indian Banks and The Future of BusinessDocumento9 páginasMacro-Economics Assignment: Npa of Indian Banks and The Future of BusinessAnanditaKarAinda não há avaliações

- The Prospect of Indonesian Banking Industry in 2010Documento8 páginasThe Prospect of Indonesian Banking Industry in 2010DoxCak3Ainda não há avaliações

- Balacesheet Analysis: Sbi Bank and Axis Bank: Vinay V. PatilDocumento16 páginasBalacesheet Analysis: Sbi Bank and Axis Bank: Vinay V. PatilVinay PatilAinda não há avaliações

- Banking Sector - Backing On Demographic DividendDocumento13 páginasBanking Sector - Backing On Demographic DividendJanardhan Rao NeelamAinda não há avaliações

- Today, You Will Read General Awareness Topic: BASEL III in India and ImpactDocumento3 páginasToday, You Will Read General Awareness Topic: BASEL III in India and ImpactNikhil BorawakeAinda não há avaliações

- Corporate Bond MKT FDDocumento6 páginasCorporate Bond MKT FDTejeesh Chandra PonnagantiAinda não há avaliações

- Equity: Read More: Under Creative Commons LicenseDocumento7 páginasEquity: Read More: Under Creative Commons Licenseyogallaly_jAinda não há avaliações

- Causes of NPADocumento7 páginasCauses of NPAsggovardhan0% (1)

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocumento9 páginasNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentgauravgorkhaAinda não há avaliações

- Outlook For Banks 2010Documento6 páginasOutlook For Banks 2010khabis007Ainda não há avaliações

- Determinants of Return On Assets of Public Sector Banks in India: An Empirical StudyDocumento6 páginasDeterminants of Return On Assets of Public Sector Banks in India: An Empirical StudytamirisaarAinda não há avaliações

- Future of Indian Banking IndustryDocumento8 páginasFuture of Indian Banking IndustrymbashriksAinda não há avaliações

- Crisis in Banking SectorDocumento7 páginasCrisis in Banking SectorShrujan SinhaAinda não há avaliações

- LOW RATE OF SBI Moody'sDocumento3 páginasLOW RATE OF SBI Moody'sVs RanaAinda não há avaliações

- 6 Banking and Financial ServicesDocumento5 páginas6 Banking and Financial ServicesSatish MehtaAinda não há avaliações

- It's A Double Whammy For Vietnam's Banks: Bad Loans Are Rising As Economic Growth FaltersDocumento6 páginasIt's A Double Whammy For Vietnam's Banks: Bad Loans Are Rising As Economic Growth Faltersapi-227433089Ainda não há avaliações

- Banking: Last Updated: July 2011Documento4 páginasBanking: Last Updated: July 2011shalini26Ainda não há avaliações

- Q3 and 9M, FY2012 Performance Review and OutlookDocumento19 páginasQ3 and 9M, FY2012 Performance Review and OutlookpvinayakamAinda não há avaliações

- Interest Rate Risk: Get QuoteDocumento5 páginasInterest Rate Risk: Get Quoterini08Ainda não há avaliações

- Industry Profile: Excellence in Indian Banking', India's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Growth Will Make TheDocumento27 páginasIndustry Profile: Excellence in Indian Banking', India's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Growth Will Make TheNekta PinchaAinda não há avaliações

- India Banking Outlook 2011: Stability Ahead, But Some Headwinds RemainDocumento10 páginasIndia Banking Outlook 2011: Stability Ahead, But Some Headwinds RemainVijaydeep SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Challenges and Coners of RbiDocumento17 páginasChallenges and Coners of RbiParthiban RajendranAinda não há avaliações

- NPA Levels Highest in 2011-12 During Last 5 Years: RBI: Non-Performing Assets in Indian BanksDocumento2 páginasNPA Levels Highest in 2011-12 During Last 5 Years: RBI: Non-Performing Assets in Indian Banksglo6riaAinda não há avaliações

- Posted: Sat Feb 03, 2007 1:58 PM Post Subject: Causes For Non-Performing Assets in Public Sector BanksDocumento13 páginasPosted: Sat Feb 03, 2007 1:58 PM Post Subject: Causes For Non-Performing Assets in Public Sector BanksSimer KaurAinda não há avaliações

- Banks: The Sri Lankan Banking SectorDocumento14 páginasBanks: The Sri Lankan Banking SectorRandora LkAinda não há avaliações

- ShambhaviDocumento4 páginasShambhaviShambhavi DoddawadAinda não há avaliações

- Executive Summary: A. The Macro Financial EnvironmentDocumento5 páginasExecutive Summary: A. The Macro Financial EnvironmentSajib DasAinda não há avaliações

- White Simple Illustration Business Financial PresentationDocumento19 páginasWhite Simple Illustration Business Financial Presentationshivansh.dwivedi1976Ainda não há avaliações

- Indian Banks Note (Revised)Documento19 páginasIndian Banks Note (Revised)zainab bharmalAinda não há avaliações

- Business Line - Sept 2013Documento3 páginasBusiness Line - Sept 2013Himadri SAinda não há avaliações

- ICRA Indian Mortgage FinanceDocumento18 páginasICRA Indian Mortgage FinancemarinemonkAinda não há avaliações

- Risk Management of Banking SystemDocumento12 páginasRisk Management of Banking Systemabhinav choudhuryAinda não há avaliações

- Financials Result ReviewDocumento21 páginasFinancials Result ReviewAngel BrokingAinda não há avaliações

- DEMONETISATIONDocumento26 páginasDEMONETISATIONMoazza Qureshi50% (2)

- Indian Banking Industry-1253Documento37 páginasIndian Banking Industry-1253ch.nagarjunaAinda não há avaliações

- Banking Sector ReformsDocumento15 páginasBanking Sector ReformsKIRANMAI CHENNURUAinda não há avaliações

- Financial Sector and Economic Growth in IndiaDocumento5 páginasFinancial Sector and Economic Growth in IndiaAnshuman DasAinda não há avaliações

- A Crisis of Banking SectorDocumento3 páginasA Crisis of Banking SectorMithesh PhadtareAinda não há avaliações

- Banking Industry OverviewDocumento14 páginasBanking Industry OverviewyatikkAinda não há avaliações

- Chinas WholesaleDocumento9 páginasChinas WholesaleNavin RajagopalanAinda não há avaliações

- Bhopal Branch of CIRC of ICAI: This Ediition SpecialDocumento26 páginasBhopal Branch of CIRC of ICAI: This Ediition SpecialShrikrishna DwivediAinda não há avaliações

- ANZ Why PBOC Has Not Been Able To Smooth Money Market RatesDocumento15 páginasANZ Why PBOC Has Not Been Able To Smooth Money Market RatesrguyAinda não há avaliações

- P PP P PP GPPP: Key Points Financial Year '10 Prospects Sector Do's and Dont'sDocumento7 páginasP PP P PP GPPP: Key Points Financial Year '10 Prospects Sector Do's and Dont'sTeja YellajosyulaAinda não há avaliações

- ProposalDocumento34 páginasProposalAli JafferyAinda não há avaliações

- Banking System in India Non Performing AssetsDocumento12 páginasBanking System in India Non Performing AssetssrikarAinda não há avaliações

- Indian Banks Loan Growth RateDocumento4 páginasIndian Banks Loan Growth RateKabilanAinda não há avaliações

- Impact of Banking Sector Npa'S On Indian EconomyDocumento9 páginasImpact of Banking Sector Npa'S On Indian EconomyKaran Veer SinghAinda não há avaliações

- 5.1 Role of Commercial BanksDocumento5 páginas5.1 Role of Commercial Banksbabunaidu2006Ainda não há avaliações

- A Critical Review of NPA Management: Challenge For Public Sector BanksDocumento7 páginasA Critical Review of NPA Management: Challenge For Public Sector Banksswati singhAinda não há avaliações

- Bank Merger: Why Merger Is Good? - Benefits For Various StakeholdersDocumento5 páginasBank Merger: Why Merger Is Good? - Benefits For Various StakeholdersAnirban RoyAinda não há avaliações

- Growth of Indian Banking Sector: Presented byDocumento26 páginasGrowth of Indian Banking Sector: Presented bylovleshrubyAinda não há avaliações

- Final Main Pages ProjectDocumento103 páginasFinal Main Pages ProjectJeswin Joseph GeorgeAinda não há avaliações

- Indonesia's Banking Industry: Progress To DateDocumento5 páginasIndonesia's Banking Industry: Progress To DateZulfadly UrufiAinda não há avaliações

- 5 A Critical Review of Basel-Iii Norms For Indian Psu Banks PDFDocumento8 páginas5 A Critical Review of Basel-Iii Norms For Indian Psu Banks PDFDhiraj MeenaAinda não há avaliações

- Swot Analysis Indian Banking: From The Selectedworks of Yogendra SisodiaDocumento6 páginasSwot Analysis Indian Banking: From The Selectedworks of Yogendra SisodiasamdhathriAinda não há avaliações

- Macroeconomic and Financial Sector BackgroundDocumento25 páginasMacroeconomic and Financial Sector BackgroundTejashwi KumarAinda não há avaliações

- SWOT Analysis of Banking SectorDocumento6 páginasSWOT Analysis of Banking SectorMidhun RajAinda não há avaliações

- EIB Working Papers 2019/07 - What firms don't like about bank loans: New evidence from survey dataNo EverandEIB Working Papers 2019/07 - What firms don't like about bank loans: New evidence from survey dataAinda não há avaliações

- Protection and Switchgear by U.a.bakshi and M.v.bakshiDocumento397 páginasProtection and Switchgear by U.a.bakshi and M.v.bakshiRajesh DharamsothAinda não há avaliações

- Sales All FNL SS06Documento1 páginaSales All FNL SS06Harsha Vardhan KambamAinda não há avaliações

- Globalization Is Anti PoorDocumento6 páginasGlobalization Is Anti PoorHarsha Vardhan KambamAinda não há avaliações

- MR. & MS. Amaze: BY Aparna Das Mary Priya Harsha Vardhan Naveen Kumar Sandeep Sunil DamodharDocumento16 páginasMR. & MS. Amaze: BY Aparna Das Mary Priya Harsha Vardhan Naveen Kumar Sandeep Sunil DamodharHarsha Vardhan KambamAinda não há avaliações

- Rural and Women EnterpreneurshipDocumento60 páginasRural and Women Enterpreneurshipgurudarshan100% (1)

- CJ-21577106-M H M ADHIL-international Trade, Finance and Investment ReportDocumento23 páginasCJ-21577106-M H M ADHIL-international Trade, Finance and Investment ReportAdhil HarisAinda não há avaliações

- GST-CHALLAN (13) KPDocumento2 páginasGST-CHALLAN (13) KPacpandey.lawfirmAinda não há avaliações

- INTERVIEW Material PNB PromotionDocumento68 páginasINTERVIEW Material PNB PromotionKuNal RehlanAinda não há avaliações

- Nodal Bank Brach Code NosDocumento43 páginasNodal Bank Brach Code Nospravin0921Ainda não há avaliações

- 2019 SX GN ObcDocumento40 páginas2019 SX GN ObcPoodari VenkateshAinda não há avaliações

- J 1 B T1 Y8 GPSspxdoyDocumento16 páginasJ 1 B T1 Y8 GPSspxdoyanandabrh567Ainda não há avaliações

- Impact of MNCs On Indian Economy-688Documento39 páginasImpact of MNCs On Indian Economy-688Jatin Kharbanda100% (1)

- Summer Internship Report On LenovoDocumento74 páginasSummer Internship Report On Lenovoshimpi244197100% (1)

- Companies Near IndoreDocumento1 páginaCompanies Near IndoreTarun GAinda não há avaliações

- Impact of DemonetizationDocumento30 páginasImpact of DemonetizationKomal Pal100% (1)

- JEE Main 2022 June 24 Question Paper KeysDocumento66 páginasJEE Main 2022 June 24 Question Paper Keyslakshya rautelaAinda não há avaliações

- BFSC PDFDocumento20 páginasBFSC PDFSindhanaa AndavanAinda não há avaliações

- DOMS401Documento345 páginasDOMS401vsimanpalliAinda não há avaliações

- Statement 1581241871570Documento13 páginasStatement 1581241871570RJ Rishabh TyagiAinda não há avaliações

- India-From Emerging To SurgingDocumento23 páginasIndia-From Emerging To Surgingdipty.joshi3709Ainda não há avaliações

- RRB Po & Asst. Mains 2023 BoltDocumento204 páginasRRB Po & Asst. Mains 2023 BoltKar ThikAinda não há avaliações

- Placement ADGITM 31st March 2022Documento28 páginasPlacement ADGITM 31st March 2022Hritik SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Programmes of Employment Generation and Poverty Alleviation in IndiaDocumento7 páginasProgrammes of Employment Generation and Poverty Alleviation in IndiaVijayalakshmi AmrutheshaAinda não há avaliações

- Three Months Economy ImpDocumento21 páginasThree Months Economy ImpskumarAinda não há avaliações

- Microeconomics: Market Analysis of Sugar Industry in IndiaDocumento10 páginasMicroeconomics: Market Analysis of Sugar Industry in IndiaSimran KaurAinda não há avaliações

- Icici 3852 19-25Documento15 páginasIcici 3852 19-25bilal lekhaAinda não há avaliações