Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

A Competency-Based Model of Sustainable Competitive Advantage

Enviado por

Huda Kouka0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

462 visualizações15 páginasArticle examines concept of sustainable competitive advantage in context of two theoreticalframeworks. Environmental determinsm and "strategic selection" frameworks are used. An alternative conceptualization is offered from a resource-based perspective.

Descrição original:

Direitos autorais

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoArticle examines concept of sustainable competitive advantage in context of two theoreticalframeworks. Environmental determinsm and "strategic selection" frameworks are used. An alternative conceptualization is offered from a resource-based perspective.

Direitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

462 visualizações15 páginasA Competency-Based Model of Sustainable Competitive Advantage

Enviado por

Huda KoukaArticle examines concept of sustainable competitive advantage in context of two theoreticalframeworks. Environmental determinsm and "strategic selection" frameworks are used. An alternative conceptualization is offered from a resource-based perspective.

Direitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 15

I6h Journal of Management

~ 1992. Vol. IS. No. 1, TI-91

A Competency-Based Model of

Sustainable Competitive Advantage:

Toward a Conceptual Integration

Augustine A. Lado

Cleveland State University

Nancy G. Boyd

University ofNorth Texas

Peter Wright

Memphis State University

This article examines the concept ofsustainable competitive advan-

tage in the context oftwo theoreticalframeworks: environmental deter-

minism (which encompasses microeconomic and industrial organiza-

tion traditions) and "strategic selection" (which incorporates

Schumpeterian economic and strategic choice perspectives). It is ar-

gued that by ascribing competitive advantage to industrylmarket im-

peratives, the YO-based model apparently overlooks the idiosyncratic

competencies that potentially generate a sustainable competitive ad-

vantage for the firm. An alternative conceptualization of sustainable

competitive advantage from a resource-based perspective is offered.

Specifically, a systems model that integrally linksfour components ofa

firm's "distinctive competencies" (managerial competencies and

strategic focus. resource-based. transfonnation-based. and output-

based competencies) is proposed.

The concept of competitive advantage drives business strategy and has re-

ceived considerable treatment in the literature. Within the strategic management

literature, we have two competing models of sustainable competitive advantage.

One is grounded in neoclassical economics (Chamberlin, 1933; Friedman, 1953)

and more explicitly dealt with in the industrial organization literature (Bain, 1956;

Hill, 1988; Porter, 1980, 1981, 1985). The other is rooted in a resource-based

view of the fIrm (Barney, 1986c, 1988; Dierickx & Cool, 1989; Lippman &

Rumelt, 1982; Reed & DeFillippi, 1990).

The I/O model views competitive advantage as a position of superior perfor-

mance that a fum achieves through offering no-frills products at low prices or of-

fering differentiated products for which customers are willing to pay a price pre-

mium (e.g. Porter, 1980, 1985). The underlying premise is that the market or

industry imposes selective pressures to which the fum must respond. Firms that

Address all COITespondence to Augustine A. Lado. Department of Management and Labor Relations. College

of Business. Cleveland Stale University, Cleveland, OH44115.

Copyright 1992 by the Southern Management Association 0149-20631921$2.00.

77

Copyright 2001. All Rights Reserved.

78 LADO, BOYD, AND WRIGHT

can successfully adapt to those industry/market requirements will survive and

grow, whereas those that fail to adapt are doomed to failure and exit from the in-

dustry/market. Thus, in the neoclassical economic and industrial organization tra-

ditions, competitive advantage is ascribed to external characteristics rather than to

the ftrm's idiosyncratic competencies and resource-based deployments.

In the resource-based model, competitive advantage is viewed from the per-

spective of the "distinctive competencies" that give a ftrm an edge over its rivals

(Barney, 1986a, 1986b; Day & Wensley, 1988; Fahey, 1989; Ghemawat, 1986;

Hitt & Ireland, 1985; Lippman & Rumelt, 1982; Reed & DeFillippi, 1990). These

studies have entertained the view of an organization as a nexus or bundle of spe-

cialized resources that are deployed to create a privileged market position (see

e.g., Barney, 1986c, 1988; Dierickx & Cool, 1989; Rumelt, 1984, 1987; Werner-

felt, 1984). Unequivocally, these works have enriched our understanding of the

concept of sustainable competitive advantage. Perhaps their greatest contribution

has been in generating alternative concepts that may serve as building blocks for

developing a theory of the ftrm" (Rumelt, 1984). In this article, the con-

cept of sustainable competitive advantage is extended in the context of resource-

based competencies. Our discussion of the concept of sustainable competitive ad-

vantage is based on the premise that ftrm-speciftc competencies are potential

rent-yielding strategic assets (Barney, 1986c, 1988; Dierickx & Cool, 1989;

Itami, 1987; Rumelt, 1987; Winter, 1987).

Our analysis assumes that these competencies do not merely "accrue" to the

fmn (from a good "ftt" with industry/environmental requirements), but may con-

sciously and systematically be developed by the willful choices and actions of the

fmn's strategic leaders (see e.g., Bourgeois, 1984; Child, 1972; Smircich & Stub-

bart, 1985; Weick, 1979). Thus, a voluntaristic (as opposed to a deterministic)

philosophical stance is adopted in our discussion of the concept of sustainable

competitive advantage. An overview of the theoretical perspectives of neoclassi-

cal economics and industrial organization economics is ftrst presented under the

rubric "environmental determinism." Then, the topic of strategic selection is dis-

cussed. The concept of sustainable competitive advantage is examined within

each of these perspectives. Subsequently, a competency-based model of sustain-

able competitive advantage is proposed.

Environmental Determinism and Competitive Advantage

Deterministic models depicting the relationship of fmns to their environments

may be found throughout the strategy-related literature. These models are influ-

enced by theoretical frameworks supplied by such disciplines as neoclassical eco-

nomics and industrial organization economics.

Neoclassical economic theory is predicated on the logic of economic efficiency

as a selective force that determines the long run survival of a fmn (e.g., Friedman,

1953). In this view, fmns are assumed to be rational with an overriding objective

of allocating scarce resources to alternative ends in such a way as to maximize

proftts. These proftts would be partly reinvested to expand productive capacity

and increase the volume of goods and services produced. Managerial competen-

cies are implicitly reduced to elements of labor input whose value is realizable

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT, VOL. 18, NO.1, 1992

Copyright 2001. All Rights Reserved.

SUSTAINABLECOMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE 79

only in combination with the other factors of production. Managerial proactive-

ness based on competencies (or limitations) are not given any serious considera-

tion. The neoclassical theory fails to provide a basis for understanding fIrm-level

strategic behavior, as it assumes away such phenomena as transaction costs, limits

on rationality, technological uncertainty, constraints on factor mobility, informa-

tional asymmetries, consumer and producer learning, and dishonest or foolish be-

havior of the fIrms' key actors (Rumelt, 1984).

Similarly, Classical industrial organization scholars have typically assumed that

the fmn can neither influence industry conditions nor its own performance. This

view, reflected by such works as Bain (1956) and Mason (1939), maintains that

"because [industry] structure determines performance, we could ignore conduct

and look directly at industry structure in trying to explain performance" (porter,

1981: 611). In this context, competitive advantage is industry driven (Le., deter-

mined by industry characteristics such as concentration ratio and cost structure)

rather than proactively created by fmns through accumulation of unique, valu-

able, and imperfectly imitable resources.

The modifIed framework advanced by a new group of I/O theorists recognizes

the role of fIrmconduct in influencing the relationship between industry structure

and fIrm performance. According to Porter (1981), "there are some fundamental

parameters of industry dictated by the basic product characteristics and technol-

ogy, but ... within those parameters, industry evolution can take many paths, ...

depending [among other things] on the strategic choices fmns actually make that

follow from their [strategic goals]" (P616). The normative implications of the

I/O-based model for strategic management are that a fmn should carefully ana-

lyze the industry in terms of its structural parameters (power of buyers, power of

suppliers, entry barriers, etc.) to assess its profItability potential (porter, 1980).

Once this is achieved, a strategy that can effectively align the fmn to the industry

and generate superiot perfonnance. pe se1ecte<i an<l.implemented. Again,

the contention here is that competitNe, determined by the in-

dustry's 1?80).

In Porter's VIew, competItIve advantage can l>esustamed by erecting bamers to

entry by potential competitors, such iSCOpe economies, experience or

learning curve effects, product requirements, and buyer

switching costs. Accordingly, flfllis i continue to raise these barriers

through reinvestment of earnings if they deter entry by poten-

tial competitors and mobility by existing:competitors across the industry's strate-

gic groups (Caves & Porter, 1977; Porter, 1980, 1985). Porter's framework also

recognizes the threat of substitute products as well as the bargaining power of

buyers and suppliers as potential moderators in achieving competitive advantage.

However, emphasis should be made that, in the context of industry structure, fmn

reinvestment may prove disadvantageous beyond a certain point when dis-

economies of scale begin to set in or when product differentiation reaches a point

of saturation.

In summary, the neoclassical and industrial organization theories tend to offer

littleunderstanding of the proactive structuring of sustainable competitive advan-

tage. By consigning competitive advantage to the imperatives of industry/market

JOURNAL OFMANAGEMENT, VOL. 18, NO. I, 1992

Copyright 2001. All Rights Reserved.

80 LADO, BOYD, AND WRIGHT

structure, these theories apparently overlook the idiosyncratic fIrm competencies

elicited from managerial volition, organizational routines, reputation, and culture

that are potential sources of sustainable competitive advantage. In the modifIed

110 version, the concept of competitive advantage is recognized and discussed

with respect to creating barriers to entry by potential competitors as well as creat-

ing mobility barriers (Caves, 1984; Caves & Porter, 1977; Porter, 1980). The

issue of how unique fIrm competencies that generate quasi-rents can be protected

from imitation by competitors has not been closely examined. Unique fmn com-

petencies have been examined by other scholars as detailed next.

Strategic Selection and Competitive Advantage

An alternative view of competitive advantage has been provided by a strategic

selection perspective. The term strategic selection is used in contradistinction to

the natural selection view to emphasize the fact that it is the pattern of strategic

decisions and actions that determines organizational survival and renewal. Al-

though "luck" may playa role in generating earnings for the fmn (Barney, 1986c;

Mancke, 1974), we argue that what constitutes good fortune or luck may alterna-

tively be conceived as the point at which stochastic opportunity and acquired/cul-

tivated fIrm-specifIc resources meet.

The strategic selection view is consistent with Schumpeterian economics of in-

novation and entrepreneurship (Barney, 1986b; Rumelt, 1984, 1987) and with se-

lect views in strategic management (Jauch & Kraft, 1986; Mintzberg & Waters,

1985; Smircich & Stubbart, 1985; Yvette & Mintzberg, 1988). It is also consistent

with interpretive sociology (Morgan, 1983, 1986; Morgan & Ramirez, 1984),

cognitive psychology (Argyris & Shon, 1978; Dutton & Jackson, 1987; Hurst,

Rush, & White, 1989; Weick, 1979), and behavioral economics (penrose, 1952;

Simon, 1947, 1984).

Emphasis should be made that the concept of strategic selection is more proac-

tive than "strategic choice." That is, the notion ofstrategic choice (Child, 1972;

Hrebiniak & Joyce, 1985) is limiting in that it implies choosing from given alter-

natives. Strategic selection, on the other hand, embraces a broader perspective to

include the capacity to create and grasp opportunities internal and external to the

fIrm. Moreover, strategic selection focuses attention on organizational variables

that are important for creating and sustaining competitive advantage. This ap-

proach to fIrm analysis explicitly recognizes managerial proactiveness in influ-

encing business performance.

The Schumpeterian premise of entrepreneurially driven "creative destruction"

(Schumpeter, 1934, 1950) has provided impetus to the resource-based model of

strategy and competitive advantage. For example, Rumelt (1984: 560) has stated:

"corporate entrepreneurship is intimately connected with the appearance and ad-

justment of unique and idiosyncratic resources." He has further argued: "En-

trepreneurs are seen to possess special information, to be unique, to create pure

profIt, and to act as the essential indivisibilities governing the size distribution of

fIrms" (1984: 561). Similarly, Leibenstein (1968, 1987) has observed that en-

trepreneurs perform special roles of "gap fIlling" and "input completion"; the for-

mer refers to identifying unmet customer needs and responding to them with a

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT, VOL. 18,NO. 1, 1992

Copyright 2001. All Rights Reserved.

:,-'------------------------

SUSTAINABLECOMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE 81

unique product offering, and the latter to the special talents (or unique competen-

cies) of organizing, leading, and motivating people to accomplish desired ends.

Additionally, Barney (1986b: 796) has stated that:

certain fIrms in an industry may have the unique skills required to be

the source of revolutionary changes in industry. '" Other fIrms may

have the unique ability to rapidly adapt to whatever revolutionary

changes might occur. ... Firms that possess either of these organiza-

tional capabilities may have a greater likelihood of survival in indus-

tries threatened by revolutionary Schumpeterian changes than fIrms

without these capabilities.

In summary, the strategic selection view provides a compelling theoretical

framework for sustainable competitive advantage. The recognition by this frame-

work that idiosyncratic competencies are created and developed by a fIrm's

agents (or entrepreneurs) suggests the need to focus on organizational phenomena

(such as informational asymmetries, organizational routines, histories, and repu-

tation) that go beyond techno-economic considerations in assessing competitive

advantage. Put in other words, implicit in the strategic selection philosophy is the

concept of unique or distinctive competencies (Selznick, 1957). An overview of

the concept of distinctive competencies and its relationship to sustainable com-

petitive advantage is presented in the following section. This information pro-

vides the background upon which our proposed model of sustainable competitive

advantage is structured.

Distinctive Competencies and Competitive Advantage

Selznick (1957) fIrst coined the term distinctive competencies to describe the

leadership capabilities that were responsible for transforming a public organiza-

tion into a successful operation. The concept was incorporated into the Learned,

Christensen, Andrews, and Guth (1969) business policy framework, which

placed emphasis on assessing internal organizational capabilities (strengths and

weaknesses) and matching these with environmental opportunities and threats.

Additionally, Ansoff (1965, 1976) discussed the concept as an integral compo-

nent of corporate strategy and subsequently argued that an organization's distinc-

tive competencies are essential to identifying and responding to weak environ-

mental signals. Hofer and Schendel (1978) have defIned distinctive competencies

as the unique competitive position that a firm achieves through its resource de-

ployment. They have also viewed competencies as an integral part of organiza-

tional strategy.

Reed and DeFillippi (1990) have further developed the concept of distinctive

competencies by relating it to sustainable competitive advantage and causal ambi-

guity. Causai ambiguity is defIned as the "basic ambiguity concerning the nature

of the causal connections between actions and results" (Lippman & Rumelt,

1982: 420). It describes the fum-specific resources and competencies (or vulnera-

bilities) that have the potential to generate superior (or inferior) performance.

Reed and DeFillippi have argued that achieving a sustainable competitive advan-

tage requires reinvestment in causally ambiguous organizational competencies

that are characterized by tacitness, complexity, and specifIcity. Tacit knowledge

JOURNALOFMANAGEMENT, VOL. 18, NO. I, 1992

Copyright 2001. All Rights Reserved.

82 LADO, BOYD, ANDWRIGHT

describes information and competencies that are non-codifiable and non-explic-

itly replicable (polanyi, 1967). Complexity describes the range of interrelation-

ships among skills and other knowledge-based competencies (Winter, 1987).

Specificity describes the extent to which resources and skills are idiosyncratic to

the firm (i.e., not easily transferrable to alternative use without substantial costs)

and can be advantageously channeled toward particular customers (Reed & De-

Fillippi, 1990; Williamson, 1985). Thus, the conceptualization of distinctive com-

petencies encompassing these and other attributes provides a rationale for view-

ing firm-specific competencies as sources of sustainable competitive advantage.

A Competency-Based Model of Sustainable Competitive Advantage

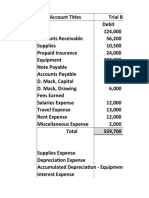

Figure I presents a systems model which integrally links four sources of com-

petencies: managerial competencies and strategic focus, input-based, transforma-

tion-based, and output-based competencies. These competencies may be valuable

to the firm and their interlinkage may lead to a unique competitive advantage that

is not subject to imitation. The basic premise of the model is that managerial com-

petencies and strategic focus are largely responsible for attracting specialized re-

sources that are synergistically combined, transformed, and channeled to select

clients in such ways as to generate a sustainable competitive advantage to the

firm. Although the components of the model are discussed individually for eluci-

dation purposes, a holistic construal of the concept of competitive advantage is

presumed.

Managerial Competencies and Strategic Focus

Ultimately, managerial values and competencies delineate the strategic focus

of the organization (Guth & Tagiuri, 1965; Hambrick & Mason, 1984). For exam-

ple, Westley and Mintzberg (1989) argue that leaders create a strategic vision,

Mllnllgerllll Competencies

lind Strllteglc Focus

Transformlltlon-Bllsed

Competencies

Figure I.

ACompetency Based Model ofSustainable Competitive Advantage

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT. VOL. 18. NO. I, 1992

Copyright 2001. All Rights Reserved.

SUSTAINABLECOMPETITIVEADVANTAGE 83

communicate it throughout the organization, and empower employees to realize

that vision. In their view, strategic vision is achieved through repetition (or exper-

imentation and improvisation), representation (or articulation of core values), and

assistance (or acceptance and legitimation of the vision by key stakeholders).

Thus, the articulated strategic vision becomes the fulcrum around which the

fIrm's unique competencies may be developed.

Effective implementation of such vision will depend crucially on the extent to

which a fIrm's managers acquire and mobilize specialized strategic resources that

may yield superior returns relative to competitors. Barney (1986c) argues that

fIrms may obtain above normal returns from the acquisition of strategic resources

by exploiting informational and expectational asymmetries in the strategic factor

markets. Thus, it takes unique managerial competencies to evaluate the expected

earnings streams accruing from strategic resources that are vital to implementa-

tion of a fIrm's strategy. Hence the arrow in Figure 1 that connects managerial

competencies and strategic focus with resource-based competencies portrays

managerial effects on specialized strategic resource acquisition and mobilization.

The influence of strategic leadership on specifIc outcomes such as organiza-

tional performance has been the subject of controversy. For example, the results

of a longitudinal study conducted by Lieberson and O'Connor (1972) indicate

that environmental factors account for more variance in organizational perfor-

mance than leadership factors. On the other hand, a subsequent replication of this

study found that the amount of variation in performance attributed to leadership

factors substantially increased when the order in which the independent variables

were entered into the analysis was changed (Weiner & Mahoney, 1981). Our

model suggests that strategic leadership (through managerial competencies) will

have a signifIcant impact on organizational strategy and performance and be a

source of sustainable competitive advantage insofar as such leadership exhibits

characteristics of uniqueness in exploiting f"mn-specific competencies.

The contention that strategy and performance are ultimately a reflection of top

managers or the dominant coalition (Cyert & March, 1963; Hambrick, 1987,

1989; Hambrick & Mason, 1984) underscores the importance of managerial com-

petencies as a source of sustainable competitive advantage. Managers are respon-

sible for developing "an overall sense of purpose and direction that guide[s] inte-

grated strategy formulation and implementation in organization" (Shrivastava &

Nachman, 1989: 51). As is evident, managerial volition is assumed in this con-

text. The deterministic alternative view (not adopted in this article) argues for the

need to match, align, or "fIt" managers to strategy (Kerr & Jackofsky, 1989; Szi-

lagyi & Schweiger, 1984).

As indicated in Figure 1, managerial competencies and strategic focus assume

a central position in creating resource-based, transformation-based, and output-

based competencies. In other words, organizational distinctive competencies may

be generated by the decisions and actions of top managers. Thus, managerial

competencies may be viewed as influencing the interaction among resource-

based, transformation-based, and output-based components of the system.

Furthermore, top managers are viewed as capable of imposing order on the en-

vironment through the selective identifIcation of strategic issues (Dutton & Jack-

JOURNAL OFMANAGEMENT, VOL 18, NO. 1,1992

Copyright 2001. All Rights Reserved.

84 LADO, BOYD, AND WRIGHT

son, 1987; Miles & Snow, 1978). That is, top managers may generate unique in-

formation that enables them to effectively interpret the firm's environment with

respect to opportunities and threats. Hence, in Figure 1, the linkages between

managerial competencies and the environment are depicted by two arrows. One

denotes the potential managerial influence on the environment and the other indi-

cates the feedback flow of information (from the environment) that is necessary

to further develop managerial competencies and strategic focus. Managerial com-

petencies are developed via cognitive and behavioral characteristics that are

unique toeach decision maker or to the top management teamof a particular firm

(Hambrick, 1989). Schoemaker (1990) has offered persuasive arguments suggest-

ing how "behavioral friction forces" can, when properly exploited, yield quasi-

rents and provide a source of sustainable competitive advantage. Specifically,

these managerial competencies may be generated through the gathering of infor-

mation, framing of problems, reaching conclusions, and learning from experience

(See Russo & Schoemaker, 1989; and Schoemaker, 1990 for a detailed treabnent

of this line of thought).

Resource-Based Competencies

Wernerfelt (1984) broadly defines a resource as "anything which could be

thought of as a strength or weakness of a given firm" (p172). More specifically,

resource-based competencies consist of core human and nonhuman assets, both

tangible and intangible, that allow a firm to outperform rival firms over a sus-

tained period of time (Oster, 1990; Wernerfelt, 1984).

In Figure 1, resource-based competencies are linked to transformation-based

competencies and to output-based competencies to suggest the synergistic inter-

actions among them. For example, a firm's innovative capabilities are dependent

upon its unique competencies for acquiring and mobilizing specialized resources.

Innovative outputs require investments in idiosyncratic transformation processes.

Subsequently, the firm's technological breakthroughs may generate desirable out-

comes that may reinforce its resource-based, transformation-based, and output-

based competencies and elicit further internal and external support for the firm's

volition (e.g., Wernerfelt, 1984). If and when an industry's structural barriers

break down as a result of Schumpeterian revolutions, those firms that have ac-

quired, mobilized, and nurtured unique and idiosyncratic skills and capabilities

may survive and grow. These resource-based competencies potentially influence

the ability of the firms to develop transformation-based and output-based compe-

tencies (Irvin & Michaels, 1989).

In order for resource-based competencies to generate quasi-rents and be a

source of sustainable competitive advantage, they must be causally ambiguous

(Lippman & Rumelt, 1982; Reed & DeFillippi, 1990). That is, they would exhibit

complex relationships with other firm-specific resources and capabilities. The

tacitness of intangible input/skill-based competencies would also enhance the dif-

ficulty of competitor imitation.

The acquisition and mobilization of resource-based competencies that poten-

tially generate a sustainable competitive advantage not only require managerial

competencies in information gathering, but also accurate expectations about the

JOURNAL OFMANAGEMENT, VOL. 18, NO. 1, 1992

Copyright 2001. All Rights Reserved.

SUSTAINABLECOMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE 85

future earning streams from these resources. This may be linked to what Barney

(1986c) has considered to be imperfections in strategic factor markets that occur

due to informational and expectational asymmetries among buyers and sellers of

strategic resources. Thus, a ftrm that has unique skills and capabilities and/or that

is lucky may earn above normal returns by buying resources that are undervalued

in the market and using these resources to implement its strategy, or by not buying

resources that are overvalued in the market. Hence, in Figure 1, the flow of inputs

from the environment to the ftrm is depicted by the arrow connecting the environ-

ment to the resource-based competencies. These inputs are subsequently syner-

gistically combined with other fmn-speciftc competencies to generate a sustain-

able competitive advantage.

Transformation-Based Competencies

Transformation-based competencies may be conceived as those organizational

capabilities that are required to advantageously convert inputs into outputs (Day

& Wensley, 1988). The notion of transformation-based competencies is also

closely linked to the "value chain" concept ftrst developed by McKinsey and Co.

and subsequently adopted as an analytical tool for strategic management by

Porter (1985). Essentially, an organization's value chain embraces discrete but re-

lated sets of activities concerned with designing, developing, producing, and mar-

keting outputs to customers. These activities may be divergently related to each

other, depending on the interlinkage of the organization's idiosyncratic competen-

cies (Gluck, 1980; Porter, 1985). As shown in Figure 1, transformation-based

competencies are interrelated with managerial competencies and strategic focus,

resource-based competencies, and output-based competencies.

Transformation-based competencies may encompass both innovation and or-

ganizational culture. Innovation (including technological, marketing, and man-

agerial, among others) provides an organization with the capability to generate

new products/processes faster than competitors (lwai, 1984; Nelson & Wmter,

1982; Wmter, 1984). Organizational culture may enhance the capacity for organi-

zationallearning and adaptation (Fiol & Lyles, 1985).

The I/O based model suggests that a fmn can achieve a low-cost competitive

advantage primarily through learning effects, economies of scale, economies of

scope, and capita1l1abor substitution (BCG, 1976; Hill, 1988; Porter, 1980, 1985).

Learning effects are usually viewed as the operations economies resulting from

repetition of activities that lead to greater learning and efficiency in production

(Hayes & Wheelwright, 1984). Scale economies are expected decreases in long-

run average costs due to capacity expansion and factor intensity. Economies of

scope result from sharing of resources among organizational units (Teece, 1980).

Capita1l1abor substitution involves substituting capital for labor or vice versa in

order to enhance efficiencies.

However, it has been argued that any low-cost position gained through learning

effects, scale/scope economies, and capita1l1abor substitution might not necessar-

ily constitute a sustainable competitive advantage (Alberts, 1989; Amit & Fersht-

man, 1989). Such efficiency gains may be imitable and consequently are likely to

be eroded over time (Amit & Fershtman, 1989; Hill, 1988; Reed & DeFillippi,

JOURNAL OFMANAGEMENT, VOL. 18, NO. 1,1992

Copyright 2001. All Rights Reserved.

86 LADO, BOYD, AND WRIGHT

1990), Furthennore, cost economies do not merely accrue from such factors as

learning effects and scale/scope economies, but also from behavioral considera-

tions that make low-cost operations possible. In a rebuttalof the "experience

curve doctrine," it has been argued that a cost advantage due to experience-curve

effects is realizable only when three behavioral traits are present in an organiza-

tion or unit: (a) volition, or the will to innovate; (b) imaginativeness, or creative

intelligence; and (c) drive, or the ability to vigorously pursue a desired goal (Al-

berts, 1989: 41). In other words, cost economies do not just accrue from techno-

economic factors; they are driven down through managerial, group, and operator

volitions. This argument implies that sustainability of a low-cost position may be

achieved through managerial and personnel efforts directed at "harnessing voli-

tion, imaginativeness and drive" to push production and operations costs below

those of competitors (Alberts, 1989: 47). Transfonnation-based competencies,

however, must be idiosyncratic to the firm in order for the ftnn to achieve a sus-

tainable competitive advantage.

Similarly, the I/O-based analysis of competitive advantage with respect to dif-

ferentiation efforts has concentrated on techno-economic variables (Buzzell &

Gale, 1987; Hill, 1988; Porter, 1985). For example, Porter (1985) lists an array of

factors that are likely to generate competitive advantage through differentiation.

These include investment in product development, facility design and layout, in-

creased advertising and promotional efforts, and customized service. Again there

is no reason to suggest that these activities cannot be imitated by competitors. As

argued previously, reinvestment in differentiation efforts, though necessary, is not

sufficient to insure sustainability of a fmn's competitive advantage.

Thus, the 1I0-based analysis of competitive advantage has not heavily empha-

sized the managerial and organizational components of competition that may play

crucial roles in creating and sustaining competitive advantage. It has been empiri-

cally shown that economic factors account for only about 15-40% of ftnn perfor-

mance (Hansen & Wemerfelt, 1988); the rest of the variance may be explained by ~

such factors as managerial competencies and organizational culture or climate.

Although the role of organizational culture in achieving a superior level of perfor-

mance has long been recognized in the organizational behavior literature (Smir-

cich, 1983; Tichy, 1983; Wilkins & Ouchi, 1983), strategy researchers have paid

relatively little attention to this important factor until recently (Barney, 1986a;

Weigelt & Camerer, 1988).

It has been recognized that for an organizational culture to provide a sustain-

able competitive advantage, it must be valuable, rare, and difficult to imitate by

competitors (Barney, 1986a). A strong organizational culture unleashes human

creative potential to generate a continuous stream of ideas that may be translated

into new products and processes. At the same time it permits realization of scale

economies and incremental learning by encouraging and rewarding "volition,

imaginativeness and drive" in the implementation of efficiency- and innovation-

enhancing strategies (Alberts, 1989).

Output-Based Competencies

Output-based competencies not only refer to a ftnn's physical outputs that de-

JOURNAL OFMANAGEMENT, VOL. 18, NO. 1, 1992

Copyright 2001. All Rights Reserved.

SUSTAINABLECOMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE 81

liver value to customers, but also to the "invisible" outputs (ltarni, 1987), such as

reputation for product and service quality, brand name, and dealer networks that

provide value to customers. A fIrm's long-run survival and growth largely de-

pends on how well value is delivered to its most important constituents--the cus-

tomers (Anderson, 1983; Day & Wens1ey, 1988). The link between output-based

competencies and the environment, as depicted in Figure 1, reflects the unique

competencies that are advantageously channeled toward creating value for cus-

tomers and that subsequently may generate a sustainable competitive advantage

for the fIrm.

The 110 paradigmhas conventionally focused on market share or relative mar-

ket share and profItability as measures of a fIrm's performance and as indicators

of strategic advantage (Gale & Buzzell, 1990). A large market share, it is argued,

indicates market power, which provides a barrier to entry for the fIrm. For exam-

ple, Schmalensee (1985) has empirically shown that industry or market factors

account for almost all the explained variance in fIrm performance, suggesting that

a larger market share is indicative of the extent to which the fIrm adapts to indus-

try forces. Accordingly, a high market share enables a fIrm to appropriate superior

returns from its investments relative to competitors (BCG, 1976; Buzzell, Gale, &

Sultan, 1976). However, in order for market share to be a source of competitive

advantage, it must be gained in such a way that it is not easily imitated by com-

petitors, and it must have stable, defmable boundaries (Day & Wensley, 1988).

In order to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage, fIrms may need to de-

liver value via service, quality, reliability, among others. For example, concern

with customer service as a competitive thrust has received much attention in

academia (Buzzell & Gale, 1987) and in the popular press (phillips, Dunkin, &

Treece, 1990). Companies such as American Express, American Airlines, and 3M

have had an enduring reputation for superior customer service that has earned

them higher returns than competitors (Phillips et al., 1990). These companies

have built unique competencies for producing and delivering quality products and

services that effectively meet customer tastes and preferences relative to competi-

tors. Thus, they earn above-normal profIts in the short run and an image for relia-

bility and dependability in dealing with customers and other clients that promote

their long-run prosperity. The reputation so earned takes time to cultivate and

replicate and so becomes a source of sustainable competitive advantage (Ghe-

mawat, 1986; Milgrom & Roberts, 1982; Weigelt & Camerer, 1988).

Concern for customers also promotes close relationships between the fIrm and

its clients (Peters & Waterman, 1982). These relationships benefIt the frrm in

gaining timely market information and brand loyalty that will generate high sales

and returns relative to competitors. Thus, the frrm earns its present reputation

through its previous relationships with customers, dealers, suppliers, and other

stakeholders. Additionally, the present quality of the frrm's relationships with its

stakeholders provides the basis for its future reputation.

Reputation building is achieved through specification of consistent product

quality and customer service requirements, provision of unconditional service

guarantees, and empowerment of employees to solve customer problems as they

arise (Hart, 1989; Irvin & Michaels, 1989). But reputation building must be a pri-

JOURNAL OFMANAGEMENT, VOL. 18, NO. 1,1992

Copyright 2001. All Rights Reserved.

88 LADO, BOYD, ANDWRIGHT

ority of top management if it is to earn a sustainable competitive advantage. Top

management contributes to the ongoing delivery of value by specifying standards

of perfonnance, communicating these clearly and unambiguously to employees,

establishing appropriate hiring, training, motivation, and reward systems for de-

veloping core skills, and boosting employee morale (Irvin & Michaels, 1989).

Conclusion

In this article, the concept of sustainable competitive advantage has been ex-

amined. Contrary to the I10-basedpropositions that ascribe competitive advan-

tage to market/industry imperatives, this study has extended the resource-based

research that places emphasis on distinctive competencies as sources of sustain-

able competitive advantage. These competencies are proactively created and

tured through the pattern of strategic decisions and actions of the fInn's agents.

This article has proposed a systems model within which the concept of sustain-

able competitive advantage can be examined. The importance of an integrative

framework for strategy research has been previously recognized (Jemison, 1981;

Mitroff & Mason, 1982). This article has incorporated such

propositions as the importance of organizational culture (Barney, 1986a; Hansen

& Wernerfelt, 1989), reputation (Weigelt & Camerer, 1988), entrepreneurship

(e.g., Rumelt, 1987), and managerial cognitive and behavioral characteristics

(Schoemaker, 1990). The presentation of sustainable competitive advantage with

respect to four sources of distinctive competencies (managerial, re-

transfonnation-based, and output-based), that are synergistically

related, allows for a holistic resource-based theoretical development. The extent

to which these four theoretical sources of distinctive competencies generate a sus-

tainable competitive advantage for a frrm is, of course, an empirical question.

The message conveyed here is that achieving and sustaining a competitive ad-

vantage position require that managers focus on developing and nurturing their

frrms' idiosyncratic competencies that inhibit imitability. Thus, frrms should con-

tinually invest in skills and capabilities that are causally ambiguous (Lippman &

Rumelt, 1982; Reed & DeFillippi, 1990), are not easily tradeable in the market

for strategic factors (Dierickx & Cool, 1989), or when acquired from such a

ket, have the potential to generate above nonnal returns (Barney, 1986c).

References

Alberts, W. W. 1989. The experience curve doctrine reconsidered. Journal ofMarketing, 53: 36-49.

Amit, R., & Fershtman, C. 1989. Avoiding some pitfalls in cost leadership strategies. In L. Fahey

(Ed.), The strategic planning management reader: 171-177. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-

Hall.

Anderson, P. F. 1983. Marketing, strategic planning and the theory of the firm. Journal ofMarket-

ing, 46(Spring): 15-26.

Ansoff, I. 1965. Corporate strategy. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Ansoff, I. 1976. Managing strategic surprise by response to weak signals. California Management

Review, 18(2): 21-33.

Argyris, C., & Shon, D. A. 1978. Organizational learning: A theory ofaction perspective. Reading,

MA: Addison:'Wesley.

Bain, J. S. 1956. Barriers to new competition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Barney, J. B. 1986a. Organizational culture: Can it be a source of sustained competitive advantage?

Academy ofManagement Review, 1l(3): 656-665.

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT, VOL. 18, NO.1, 1992

Copyright 2001. All Rights Reserved.

SUSTAINABLECOMPEI'ITIVE ADVANTAGE 89

Barney, J. B. 1986b. Types of competition and the theory of strategy: Toward an integrative frame-

work. Academy ofManagement Review, 11(4): 791-800.

Barney, J. B. 1986c. Strategic factor markets, expectations, luck, and business strategy. Manage-

ment Science, 42(10): 1231-1241.

Barney, 1. B. 1988. Returns to bidding firms in mergers and acquisitions: Reconsidering the related-

ness hypothesis. Strategic Management Journal, 9: 71-78.

Boston Consulting Group, Inc. 1976. Perspectives on experience. Boston, MA: Boston Consulting

Group.

Bourgeois, L. J. 1984. Strategic management and determinism. Academy ofManagement Review,

9(4): 586-5%.

Buzzell, R., & Gale, B. 1987. The PIMSprinciples. New York: Free Press.

Buzzell, R. D., Gale, B. T., & Sultan, R. G. M. 1976. Market share: A key to profitability. Harvard

Business Review, January-February: 97-106.

Caves, R. E. 1984. Economic analysis and the quest for competitive advantage. AEA Papers and

Proceedings, May: 124-132.

Caves, R. E., & Porter, M. E. 1977. From entry barriers to mobility barriers: Conjectural decisions

and contrived deterrence to newcompetition. Quarterly Journal ofEconomics, 91: 241-262.

Chamberlin, E. H. 1933. The theory ofmonopolistic competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univer-

sity Press.

Child, 1. 1972. Organizational structure, environment and performance: The role of strategic choice.

Sociology, 6: 2-22.

Cyert, R., & March, 1. 1963. A behavioral theory ofthefirm. Englewood-Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Day, R. H., & Wensley, R. 1988. Assessing advantage: Aframework for diagnosing competitive su-

periority. Journal ofMarketing, 52: 1-20.

Dierickx, I., & Cool, K. 1989. Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive advan-

tage. Management Science, 35(12): 1504-1511.

Dutton, J. E., & Jackson, S. E. 1987. Categorizing strategic issues: Links to organizational action.

Academy ofManagement Review: 12(1): 76-90.

Fahey, L. 1989. Discovering your firm's strongest competitive advantages. In L. Fahey (Ed.), The

strategic planning management reader: 18-22 Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Fiol, C. M., & Lyles, M. A. 1985. Organizationalleaming. Academy ofManagement Review, 10(4):

803-813.

Friedman, M. 1953. The methodology of positive economics. In M. Friedman (Ed.). Essays in posi-

tive economics: 3-43. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Gale, B. T., & Buzzell, R. D. 1990. Market position and competitive strategy. In G. S. Day, B. Weitz,

& R. Wensley (Eds.), The interface of marketing and strategy: 193-229. Greenwich, CT: JAI

Press. '

Ghemawat, P. 1986. Sustainable advantage. Harvard Business Review, September-October: 53-58.

Gluck, R. W. 1980. Strategic choice and resource allocation. The McKinsey Quarterly, Wmter: 22-

33.

Guth, W. D., & Tagiuri, R. 1%5. Personal values and corporate strategy. Harvard Business Review,

September-October: 123-132.

Hambrick, D. C. 1987. Top management teams: Key to strategic success. California Management

Review, 30(Fall): 88-108.

Hambrick, D. C. 1989. Guest editor's introduction: Putting top managers back in the strategy pic-

ture. Strategic Management Journal, 10: 5-15.

Hambrick, D. C., & Mason, P. A. 1984. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top

managers. Academy ofManagement Review, 9(2): 193-206.

Hansen, G. S., & Wernerfelt, B. 1989. Determinants of firm performance: The relative importance

of economic and organizational factors. Strategic Management Journal, 10: 399-411.

Hart, C. W. L. 1989. The power of unconditional service guarantees. The McKinsey Quarterly,

Summer: 72-87.

Hayes R. H., & Wheelwright, S. C. 1984. Restoring our competitive edge: Competing through man-

ufacturing. New York: John Wiley.

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT, VOL. 18,NO. 1,1992

Copyright 2001. All Rights Reserved.

90 LADO, BOYD, AND WRIGHT

Hill, C. W. L. 1988. Differentiation versus low cost or differentiation and low cost: A contingency

frarnework. Academy ofManagement Review, 13(3): 401-412.

Hitt, M. A., & Ireland, R. D. 1985. Corporate distinctive competence, strategy, industry and perfor-

mance. Strategic Management Journal, 6: 273-293.

Hofer, C. W., & Schendel, D. 1978. Strategyformulation: Analytical concepts. St. Paul, MN: West.

Hrebiniak, L. G., & Joyce, W. F. 1985. Organizational adaptation: Strategic choice and environmen-

tal determinism. Administrative Science Quarterly, 30: 336-349.

Hurst, D. K., Rush, J. C., & White, R. E. 1989. Top management teams and organizational renewal.

Strategic Management Journal, 10: 87-105.

Irvin, R. A., & Michaels, E. G., III. 1989. Core skills: Doing the right things right. The McKinsey

Quarterly, Summer: 4-19.

Itami, H. 1987. Mobilizing invisible assets. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Iwai, K. 1984. Schumpeterian dynamics: Technological progress, firm growth and 'economic selec-

tion.' Journal ofEconomic Behavior and Organization, 5: 321-351.

Jauch, L. R., & Kraft, K. L. 1986. Strategic management of uncertainty. Academy ofManagement

Review, 1l(4): 777-790.

Jemison, D. B. 1981. The importance of an integrative approach to strategic management research.

Academy ofManagement Review, 6: 601-608.

Kerr, J. L. & Jackofsky, E. F. 1989. Aligning managers with strategies: management development

versus selection. Strategic management Journal, 10: 157-170.

Learned, E. P., Christensen, C. R., Andrews, K. R., & Guth, W. 1969. Business Policy. Homewood,

IL: Irwin.

Leibenstein, H. 1968. Entrepreneurship and development. American Economic Review, 58(May):

72-83.

Leibenstein, H. 1987. Entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial training, and X-efficiency theory. Journal

ofEconomic Behavior and Organization, 8: 191-205.

Lieberson, S., & O'Connor, J. F. 1972. Leadership and organizational performance: A study of

larger corporations. American Sociological Review, 37: 117-130.

Lippman, S. A., & Rumelt, R. P. 1982. Uncertain imitability: An analysis of interfirm differences in

efficiency under competition. The Bell Journal ofEconomics, 13: 418-438.

Mancke, R. B. 1974. Causes of interfirm profitability differences: A new interpretation of the evi-

dence. Quarterly Journal ofEconomics, 88: 181-193.

Mason, E. S. 1939. Price and production policies of large-scale enterprises. American Economic Re-

view, 29(March): 61-74.

Miles, R. E., & Snow, C. C. 1978. Organizational strategy, structure, andprocess. New York: Mc-

Graw-Hill.

Milgrom, P., & Roberts, J. 1982. Predation, reputation, and entry deterrence. Journal ofEconomic

Theory, 27: 280-312.

Mintzberg, H., & Waters, J. A. 1985. Of strategies, deliberate and emergent. Strategic Management

Journal, 6: 257-272.

Mitroff, I. I., & Mason, R. O. 1982. Business policy and metaphysics: Some philosophical consider-

ations. Academy ofManagement Review, 7(3): 361-371.

Morgan, G. 1983. Rethinking corporate strategy: A cybernetic perspective. Human Relations, 36:

345-360.

Morgan, G. 1986. Images oforganization. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Morgan, G., & Ramirez, R. 1984. Action learning: A holographic metaphor for guiding social

change. Human Relations, 37: 1-28.

Nelson, R. R., & Winter, S. 1982. An evolutionary theory of economic change. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Oster, S. M. 1990. Modem competitive analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

Penrose, E. T. 1952. Biological analogies in the theory of the firm. American Economic Review, 5:

504-519.

Peters, J. T., & Waterman, R. H. 1982. In search ofexcellence. New York: Warner.

Phillips, S., Dunkin, A., & Treece, J. B. 1990. King customer: At companies that listen hard and re-

spond fast, bottom lines thrive. Business Week, March 12: 88-94.

JOURNAL OFMANAGEMENT, VOL. 18,NO. 1,1992

Copyright 2001. All Rights Reserved.

SUSTAINABLECOMPETITIVEADVANTAGE 91

Polanyi, M. 1967. The tacit dimension. Garden City, NY: Anchor.

Porter, M. E. 1980. Competitive strategy. New York: Free Press.

Porter, M. E. 1981. The contributions of industrial organization to strategic management. Academy

ofManagement Review, 6(4): 609-620.

Porter, M. E. 1985. Competitive advantage. New York: Free Press.

Reed, R., & DeFillippi, R. 1990. Causal ambiguity, barriers to imitation, and sustainable competi-

tive advantage. Academy ofManagement Review, 15(1): 88-102.

Rumelt, R. P. 1984. Toward a strategic theory of the finn. In R. Lamb (Ed.), Competitive strategic

management: 556-570. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Rumelt, R. P. 1987. Theory, strategy, and entrepreneurship. In DJ. Teece (Ed.), The competitive

challenge: 139-158. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger.

Russo, J. W., &Schoemaker, P. J. H. 1989. Decision traps: Ten barriers to brilliant decision making

and how to overcome them. Doubleday: New York.

Schoemaker, P. J. H. 1990. Strategy, complexity and economic rent. Management Science, 36(10):

1178-1192.

Schmalensee, R. 1985. Do markets differ much? American Economic Review, 75: 341-351.

Schumpeter, J. A. 1934. The theory ofeconomic development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Schumpeter, J. A. 1950. Capitalism, socialism, anddemocracy (3rd ed). New York: Harper & Row.

Selznick, P. 1957. Leadership in administration: A sociological interpretation. New York: Harper &

Row.

Shrivastava, P., & Nachman, S. A. 1989. Strategic leadership patterns. Strategic Management Jour-

nal, 10: 51-66.

Simon, H. A. 1947. Administrative behavior. New York: MacMillan.

Simon, H. A. 1984. On the behavioral and rational foundations of economic dynamics. Journal of

Economic Behavior and Organization, 5: 35-55.

Smircich, L. 1983. Concepts of culture and organizational analysis. Administrative Science Quar-

terly, 28: 339-358.

Smircich, L., & Stubbart, C. 1985. Strategic management in an enacted world. AcademyofManage-

ment Review, 10: 724-736.

Szilagyi, A., & Schweiger, D. M. 1984. Matching managers to strategies: A review and suggested

framework. Academy ofManagement Review, 9(4): 626-637.

Teece, D. J. 1980. Economies of scope and the scope of the enterprise. Journal ofEconomic Behav-

iorand Organization. 1: 223-247.

Tichy, N. 1983. Managing strategic change: Technical, political, and cultural dynamics. New York:

John Wiley.

Weick, K. E. 1979. The social psychology oforganizing. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Weigelt, K., & Camerer, C. 1988. Reputation and corporate strategy: Areview of recent theory and

applications. Strategic Management Journal, 9: 443-454.

Weiner, N., & Mahoney, T. A. 1981. A model of corporate performance as a function of environ-

mental, organizational, and leadership influences. Academy ofManagement J o u r n a ~ 24(3): 453-

470.

Wernerelt, B. 1984. Aresource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5: 171-180.

Westley, E, & Mintzberg, H. 1989. Visionary leadership and strategic management. Strategic Man-

agement Journal, 10: 17-32.

Wilkins, A., & Ouchi, W. 1983. Efficient cultures: Exploring the relationship between culture and

organizational performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28: 468-481.

Williamson, O. E. 1985. The economic institutions of capitalism. New York: Free Press.

Winter, S. G. 1984. Schumpeterian competition in alternative technological regimes. Journal of

Economic Behavior and Organization, 5: 287-320.

Winter, S. G. 1987. Knowledge and competence as strategic assets. In D. J. Teece, (Ed.), The com-

petitive challenge: 159-184. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger.

Yvette, M., & Mintzberg, H. 1988. Strategy making as craft. In K Urabe, J. Child, & T. Kagono

(Eds.), Innovation and management: International comparisons: 167-196. New York: Walter de

Gruyter.

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT, VOL. 18, NO.1, 1992

Copyright 2001. All Rights Reserved.

Você também pode gostar

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- 1.a. Taxi Articles of IncorporationDocumento6 páginas1.a. Taxi Articles of IncorporationNyfer JhenAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Top Activist Stories - 5 - A Review of Financial Activism by Geneva PartnersDocumento8 páginasTop Activist Stories - 5 - A Review of Financial Activism by Geneva PartnersBassignotAinda não há avaliações

- Letter of Appointment ArchitectDocumento4 páginasLetter of Appointment ArchitectPriyankAinda não há avaliações

- International Human Resource ManagementDocumento42 páginasInternational Human Resource Managementnazmulsiad200767% (3)

- Maharashtra Blacklisted Engineering CollegesDocumento3 páginasMaharashtra Blacklisted Engineering CollegesAICTEAinda não há avaliações

- Standard Operating Procedure For Customer ServiceDocumento8 páginasStandard Operating Procedure For Customer ServiceEntoori Deepak ChandAinda não há avaliações

- Leadership Case Study 8Documento6 páginasLeadership Case Study 8shakeelsajjad100% (1)

- Mega Cities ExtractDocumento27 páginasMega Cities ExtractAnn DwyerAinda não há avaliações

- A Guide To Business PHD ApplicationsDocumento24 páginasA Guide To Business PHD ApplicationsSampad AcharyaAinda não há avaliações

- IT project scope management, requirements collection challenges, defining scope statementDocumento2 páginasIT project scope management, requirements collection challenges, defining scope statementYokaiCOAinda não há avaliações

- Balance Sheet Analysis FY 2017-18Documento1 páginaBalance Sheet Analysis FY 2017-18AINDRILA BERA100% (1)

- History of JollibeeDocumento8 páginasHistory of JollibeeMailene Almeyda CaparrosoAinda não há avaliações

- Spentex Industries LTD 2011Documento10 páginasSpentex Industries LTD 2011rattanbansalAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Taxpayer Identification Number (TIN) 2 RDO Code 3 Contact Number - 4 Registered NameDocumento3 páginas1 Taxpayer Identification Number (TIN) 2 RDO Code 3 Contact Number - 4 Registered NameRose O. DiscalzoAinda não há avaliações

- 21 Cost Volume Profit AnalysisDocumento31 páginas21 Cost Volume Profit AnalysisBillal Hossain ShamimAinda não há avaliações

- New User ManualDocumento2 páginasNew User ManualWilliam Harper LanghorneAinda não há avaliações

- FNVBDocumento26 páginasFNVBpatrick hughesAinda não há avaliações

- Business Practices of CommunitiesDocumento11 páginasBusiness Practices of CommunitiesKanishk VermaAinda não há avaliações

- Digital Finance and Its Impact On Financial InclusDocumento51 páginasDigital Finance and Its Impact On Financial InclusHAFSA ASHRAF50% (2)

- Leadership: Chapter 12, Stephen P. Robbins, Mary Coulter, and Nancy Langton, Management, Eighth Canadian EditionDocumento58 páginasLeadership: Chapter 12, Stephen P. Robbins, Mary Coulter, and Nancy Langton, Management, Eighth Canadian EditionNazish Afzal Sohail BhuttaAinda não há avaliações

- Trial Balance Accounting RecordsDocumento8 páginasTrial Balance Accounting RecordsKevin Espiritu100% (1)

- Strategic Change ManagementDocumento38 páginasStrategic Change ManagementFaisel MohamedAinda não há avaliações

- Human Resource Department: Subject: General PolicyDocumento19 páginasHuman Resource Department: Subject: General PolicyAhmad HassanAinda não há avaliações

- Developing Lean CultureDocumento80 páginasDeveloping Lean CultureJasper 郭森源Ainda não há avaliações

- Tax Invoice SummaryDocumento1 páginaTax Invoice SummaryAkshay PatilAinda não há avaliações

- Clause 35 30062010Documento8 páginasClause 35 30062010Dharmesh KothariAinda não há avaliações

- Economic Growth of Nepal and Its Neighbours PDFDocumento12 páginasEconomic Growth of Nepal and Its Neighbours PDFPrashant ShahAinda não há avaliações

- 26Documento31 páginas26Harish Kumar MahavarAinda não há avaliações

- 70 Important Math Concepts Explained Simply and ClearlyDocumento41 páginas70 Important Math Concepts Explained Simply and ClearlyDhiman NathAinda não há avaliações

- Shankara Building Products Ltd-Mumbai Registered Office at Mumbai GSTIN Number: 27AACCS9670B1ZADocumento1 páginaShankara Building Products Ltd-Mumbai Registered Office at Mumbai GSTIN Number: 27AACCS9670B1ZAfernandes_j1Ainda não há avaliações