Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

A LMX Model Relating Multi-Level Antecedents To The LMX Relationship and Citizenship Behavior Grean & Uhl Bien 1995

Enviado por

shafiudinomarDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

A LMX Model Relating Multi-Level Antecedents To The LMX Relationship and Citizenship Behavior Grean & Uhl Bien 1995

Enviado por

shafiudinomarDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

A LMX Model: Relating Multi-level Antecedents to the LMX Relationship and Citizenship Behavior

SeungYong Kim University of Memphis Fogelman College of Business & Economics Memphis, TN 38152 901-678-7541 voice 901-678-2685 fax skim1@memphis.edu

Robert R. Taylor University of Memphis Fogelman College of Business & Economics Memphis, TN 38152 901-678-4551 voice 901-678-2685 fax rrtaylor@cc.memphis.edu

This paper is submitted to the Organizational Behavior & Organizational Theory track of the Midwest Academy of Management Association Conference, 2001.

INTRODUCTION Leader-member exchange refers to the differentiated relationship between a leader and a subordinate (Martin, Taylor, O'Reilly, & McLaurin, 1999). Unlike traditional leadership theories, leader-member exchange (LMX) theory maintains that a leader would develop differentiated relationships with different subordinates because of several situational and personal factors posed on the leader and the members (Deluga, 1998; Dienesch & Liden, 1986; Graen & UhlBien, 1995). Since first proposed by Graen and his colleagues (Dansereau, Cashman, & Graen, 1976; Dansereau, Graen, & Haga, 1975; Graen, 1976), intensive research attention has been devoted to the study of various facets of LMX (Gestner & Day, 1997) and the LMX development process (Bauer & Green, 1996; Dienesch & Liden, 1986; Sparrowe & Liden, 1997). Two literature reviews by Dienesch & Liden (1986) and Graen & Uhl-Bien (1995) well summarize the then current status of LMX studies. While the first review by Dienesch & Liden (1986) primarily discussed the LMX construct per se, especially with respect to the development process of LMX and dimensionality, Graen and Uhl-Biens (1995) review focused on the relationships between LMX and other organizational variables. They summarized the history of LMX studies into four stages: (a) work socialization and vertical dyad linkage, where the focus was on the discovery of differentiated dyads, (b) LMX studies focusing on the relationship and its outcomes, (c) description of dyadic partnership building for prescriptive purposes, and (d) expansion of dyadic partnership to group and network levels. These literature reviews revealed that at least two important factors are not fully incorporated into the LMX literature. The first deals with the fact that since the latter two categories are a fairly recent development (Gerstner & Day, 1997), some important group level variables (e.g., group cohesion and work-group task type) have rarely been incorporated into LMX studies. For example, the antecedents of LMX, which have been studied in many empirical studies, have not gone beyond the category of individual level and/or personal characteristics, such as personality (Deluga, 1998; Murphy & Ensher, 1999), liking (Engle & Lord, 1997), similarities (Bauer & Green, 1996; Engle & Lord, 1997; Murphy & Ensher, 1999; Sparrowe & Liden, 1997), trust (Deluga, 1994; Martin, Taylor, O'Reilly, & McLaurin, 1999), and personal characteristics (Dienesch & Liden, 1986). Similarly, many of the conceptual LMX models are also limited to the personal characteristic variables (e.g., Bauer & Green, 1996; Dienesch & Liden, 1986). Although some models included contextual factors, such as organizational policy, leaders power, organizational culture, work group composition (Dienesch & Liden, 1986), and the effect of social networks (Sparrowe & Liden, 1997), those factors were not clearly and fully explained. This tendency to focus on individual level variables is also shown in the LMX studies that examined the outcome of LMX. For example, although a number of studies suggested and found positive relationships between LMX relationship and OCB, which is one of the important outcome variables of LMX relationship (Deluga, 1994, 1998; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Paine, Bachrach, 2000; Wayne, Shore, & Liden, 1997; Wayne & Green, 1993), the effect of group-level variables on the relationship between LMX and OCB has not been considered. This gap in the literature led Podsakoff, et al. (2000) to call for studies that incorporate some important grouplevel variables, such as work-group task type and group cohesions. Another avenue that has had only little research attention in LMX studies is the effect of job characteristics on LMX. Since the development of LMX is based on the characteristics of the working relationship (Graen & Uhl-Bein, 1995), it is intuitively obvious that the nature of these -1-

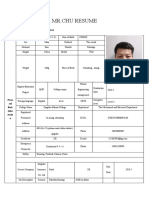

work may have some influence on the development of LMX (Dunegan, Duchon, & Uhl-Bien, 1992) and then ultimately on various outcomes. However, only very few LMX studies have dealt with job characteristic variables (Dunegan, Duchon, & Uhl-Bien, 1992; Graen & Ginsburgh, 1977; Graen & Novak, 1982; Seers & Graen, 1984). Even these studies focused on whether there was a moderating effect between a given quality of LMX and given task characteristics, rather than the direct effect of task characteristics on the quality of LMX. The consideration of group-level variables and job characteristic variables as the antecedents of LMX can not only broaden the understanding of the sources of the differentiated relationship, but can also provide both a leader and a subordinate with more opportunities for developing a better leader-member relationship in the working environment. Unlike the current LMX literature, which suggests that primarily the individual characteristics highly determine the quality of LMX, a more expanded model will allow a researcher to take a broader configurational perspective that the same quality of LMX can be developed through a different combination of various antecedents. Therefore, the purpose of the current paper is to propose a new LMX model that incorporates some group level variables and job characteristic variables into the current understanding of the LMX relationship and at least one important outcome variable, OCB. While a comprehensive model is always desirable, discussing all relevant variables is obviously beyond the scope of one paper. As the first step for incorporating group level variables and job characteristic variables into the LMX literature, this paper will propose a LMX model, in which only some selected variables are incorporated. More specifically, the model will incorporate group cohesion and work-group task type as representative group-level variables, along with job characteristics and individual perception of similarity as the antecedents of LMX, which in turn mediates the relationships between those antecedents and organizational citizenship behaviors (see Figure 1). In following section, each construct and the relationships specified in the model will be discussed, and specific propositions based on the model will be developed. -----------------------------------------------------Insert Figure 1 about here. ------------------------------------------------------

LEADER-MEMBER EXCHANGE AND OCB ORGANIZATIONAL CITIZENSHIP BEHAVIORS

Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) LMX theory is based on two primary theories: role theory and social exchange theory (Dienesch & Liden, 1986; Graen, 1976; Sparrowe & Liden, 1997). According to role theory, work in the organizational context is thought to be accomplished through the development and exchange of roles (Graen, 1976), more specifically through the series of participant exchanges of role episodes (Graen & Scandura, 1987). In Graen & Scanduras (1987) model, it was suggested that the exchange process consists of three stages: role taking, role making, and role routinization. These stages have been evolved into many LMX development process models

-2-

(e.g., Bauer & Green, 1996; Dienesch & Liden, 1986; Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995; Sparrowe & Liden, 1997). While role theory provides LMX studies with one part of the theoretical grounding by describing how leader-member relationships can be developed, social exchange theory provides yet more another theoretical ground work for LMX studies by explaining why leaders and members try to initiate and continue the relationship (Sparrowe & Liden, 1997). This theory suggests that people in an organizational context exchange not only physical materials but also psychological and emotional support and favors in their relationship (Yukl, 1989). Based on social-exchange theory, LMX theory suggests that "each party must offer something the other party sees as valuable and each party must see the exchange as reasonably equitable or fair" (Graen & Scandura, 1987: 182). Something being exchanged between a leader and a member can vary from more specific material resources and information to even emotional support (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). The greater the perceived value of the tangible and intangible commodities exchanged, the higher the quality of the LMX relationship. With high quality of LMX, dyad members are expected to experience a greater perception of reciprocal contribution and affective attachment to their counterparts. Consequently, they are more likely to develop a professional respect toward their counterparts and become more loyal to each other (Dienesch & Liden, 1986; Liden & Masyln, 1998). Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) Organizational citizenship behavior can be defined as individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and that in the aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization (Organ, 1988). OCB can be a vital factor for an organization or a group to be successful, because all business activities required for an organization to be successful cannot be anticipated and stated in job descriptions. (George & Brief, 1992). Five categories of OCB have been associated with organizational effectiveness, including courtesy, altruism, conscientiousness, civic virtue, and sportsmanship (Graham, 1986; Organ, 1988). Courtesy involves behaviors directed at the prevention of future problems, whereas altruism refers to optional contributions that help a specific coworker with a particular issue. Conscientiousness describes subordinate activity that exceeds minimum job role standards. In comparison to altruism, in which assistance is provided to a coworker, the impact of conscientiousness is more general (Organ, 1988). Next, civic virtue includes subordinate involvement in the political life of the organization (Graham, 1986). Finally, sportsmanship characterizes subordinates who pleasantly endure the aggravations that are an unavoidable element of nearly any organizational setting (Organ, 1988). LMX OCB & Work-Group Task Type as a Moderator In the current LMX literature, LMX has been hypothesized to lead to more OCB, and this relationship has been supported by a number of studies (e.g., Dansereau et al., 1975; Deluga, 1994, 1998; Liden & Graen, 1980; Settoon et al., 1996; Vecchio & Gobdel, 1984; Wayne & Ferris, 1990; Wayne, Shore, & Liden, 1997). The rationale for this relationship is that subordinates in a high LMX relationship become loyal to a leader and experience an obligation to reciprocate the leaders support. This experience, in turn, leads to more OCB (Wayne & Green, 1993). Also, although OCB is not formally rewarded, OCB may be informally rewarded -3-

with more resources and emotional support through the higher quality LMX (Deluga, 1998; Wayne & Green, 1993). Since subordinates perceive these as advantages, they are motivated to keep the advantages. With this rationale, most of LMX studies have assumed that higher LMX would have a linear relationship with OCB. However, the relationship may be more complex. As briefly stated earlier, OCB has been categorized into five groups: courtesy, altruism, conscientiousness, civic virtue, and sportsmanship (Graham, 1986; Organ, 1988). While three of them (i.e., courtesy, civic virtue, and sportsmanship) were defined in more general terms, the other two categories (i.e., altruism and conscientiousness) were more specifically defined with relation to given jobs. That is, the behaviors falling into those two categories are those helping other members work (altruism) or doing more of their own work (conscientiousness). Since these behaviors are related to given jobs, they are more likely to be subject to work-group task types. In other words, the natures of the work may be more likely to affect certain kinds of OCBs than others. Steiners (1972) typology of group tasks is helpful for further discussion. He classified group tasks into three different categories: additive, disjunctive, and conjunctive. Additive tasks are highly divisible into minimal units and easily transferred from one person to another. With additive tasks, group performance depends on each members input, combined in a simple summative fashion. Disjunctive tasks are those that cannot be dividable to sub-units. In other words, the task cannot be divided and assigned to group members. Only one member should and/or can do the entire task. The product of this type of task is actually an individual product yet sanctioned by the group. With disjunctive tasks, group performance depends on the performance of its best member. For example, the performance a high school in a nationwide math competition will be determined by the performance of a student who represents the school. Conjunctive tasks are similar to additive tasks in that they can be divisible into minimum units. However, conjunctive tasks involve a bottleneck task. Thus, with conjunctive tasks, group performance depends on the performance of the member working on the bottleneck task. These group task characteristics have important implications with relation to OCB. For example, if the given jobs were highly divisible to minimal units and could be transferred from one person to another and conducted with no difficulty (additive tasks), the chance for altruistic and conscientiousness types of OCB would be increased, since one person can easily help another persons work. It would be the same case, if the given tasks were conjunctive, since other individuals would be able to help the person who works on the bottleneck task. However, if the task is highly disjunctive, then the case would be either that the extent to which each member can help other members would be highly restricted (altruistic OCB) or that there is no need for more input (conscientiousness type OCB) per person. For instance, in contrast to single discipline work groups, multidisciplinary team members may not be able to cover the work of other team members, since they do not have the technical backgrounds in all discipline areas which are represented on the cross-functional team (Uhl-Bien & Graen, 1992). However, even in this case, other types of OCB (i.e., courtesy, civic virtue, and sportsmanship) can be done by other members and valued both by members and the leader. Therefore, the following proposition can be suggested. Proposition 1a: With additive and conjunctive tasks, high quality of LMX will lead to more OCB in all OCB types. Proposition 1b: With disjunctive tasks, high quality of LMX will lead to more OCB but only the courtesy, civic virtue, and sportsmanship types.

-4-

GROUP COHESION, LMX, & OCB Group Cohesion & OCB With two theoretical backgrounds (i.e., role theory and social exchange theory) providing justification, typical LMX models have focused on vertical dyadic relationships (e.g., supervisor subordinate), based on the assumption that a persons immediate supervisor will be the most influential in determining employee behavior (Dienesch & Liden, 1986). However, as many researchers (Dunegan, Tierney, & Duchon, 1992; Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995; Katz & Khan, 1978) have pointed out, this assumption may be spurious in a complex organizational context. Rather, the relationship is often characterized by complicated leader-member and/or member-member interactions in conducting group-tasks (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). There may be limits to eithers influence. With respect to leader-member interaction, while a manager may be empowered to make hiring, firing, and transferring decisions, once a person is in a certain division, the idiosyncratic characteristics of employees are a relatively stable given. This means that a leaders behavior with relation to his or her subordinates would be restricted by the given set of subordinates. This restricted leaders behavior is further restricted by the interactions emerging among work group members, who are mutually influenced by each others personalities, needs, and motivations. While a manager is not powerless to affect work group dynamics, most of what he/she can do is limited to indirect strategies (i.e., redesigning tasks, changing group member membership through hiring, firing, transferring, etc.) (Dunegan, Tierney, & Duchon, 1992). It should be obvious that a leader-member relationship will thus be influenced not only by the immediate supervisor but also by group level interactions. Among various group-level variables that may affect the leader-member relationship, the level of group cohesion may be one of the most important (Hackman, 1992). Group cohesion can be defined as the extent to which group members have an affinity for one another and desire to remain part of the group (Kidwell, Mossholder, & Bennett, 1997). In cohesive work groups, individuals tend to be more sensitive to others and are more willing to aid and assist them (Schachter, Ellertson, McBride, & Gregory, 1951). Cohesiveness has been shown to lead to greater intra-group communication, stronger group influence, and more favorable interpersonal evaluations within groups (Cartwright, 1968). Group cohesiveness has been identified as an important situational antecedent to affiliative/promotive behaviors (Van Dyne, Cummings, & Parks, 1995) like OCB. The higher group cohesiveness, the more the group members are likely to experience positive mood (Gross, 1954; Marquis, Guetzkow, & Heynes, 1951), which is in turn more likely to induce altruistic behaviors towards others (Isen & Baron, 1991). One study found that group cohesiveness explains more variance in OCB than individual job satisfaction (Kidwell, Mossholder, & Bennett, 1997). Therefore, Proposition 2a: group cohesion will be positively related to the amount of OCB exhibited by group members. Group Cohesion & LMX With respect to LMX, group cohesion functions in two ways. First, group cohesion can serve as one of the primary substitutes for leadership in an organizational context (Gordon, -5-

1994). In other words, group cohesion can lead to and facilitate an important source of performance feedback and provide behavioral standards based on group norms (Hackman, 1992). If the cohesive group can provide some necessary resources of information and performance guidelines (e.g., feedback, support, and behavioral guidelines) that a leader usually does, then the need for developing higher LMX relationship may be diminished. In their study, Dobbins & Zaccaro (1986) examined the effect of group cohesion on leaders behavior and found that group cohesion moderates the relationship between leader behavior and subordinate satisfaction. Second, high group cohesion may prevent subordinates from attempting to develop a high quality of LMX. Since high group cohesion entails the perception of strong ties among group members (Krackhardt, 1992), anything perceived as a threat to those ties perception might be systematically resisted by group members. LMX theory suggests that a high quality of LMX would lead to higher performance, because a subordinate would get more resources from a leader. This means that a leader differentiates the relationships with his or her subordinates not only in terms of emotional support but also physical resource distribution (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). However, this differentiated distribution of resources and benefits can be perceived by other subordinates as something unfair or as a threat (e.g., rate-busting) to reduce group cohesiveness (Scandura, 1999). If so, the subordinates who benefit from the high quality of LMX may experience some peer group pressure to refrain from maintaining a high quality exchange relationship with a supervisor (Dunegan, Duchon, & Uhl-Bien, 1992). Although no empirical study that has directly examined this relationship is available, some studies based on social network theory appear to support this reasoning. Krackhardt (1992, 1995:6) argued that social networks that are composed of densely connected, strongly tied relationships may function to reduce individuality and individual power, and that individuals within these groups experience less freedom and are more constrained by the groups norms than people who are only part of a strong dyadic relationship. Therefore, Proposition 2b: Group cohesion will be negatively related to the quality of LMX JOB CHARACTERISTICS AND LMX Since the development of LMX is based on the characteristics of the working relationship (Graen & Uhl-Bein, 1995), some job characteristics can be thought to have influence on the development of LMX to some extent (Dunegan, Duchon, & Uhl-Bien, 1992). However, only few studies have examined the relationship between job characteristics and LMX (Aldag & Brief, 1977; Dunegan, Duchon, & Uhl-Bien, 1992; Ferris & Rowland, 1981; Graen & Ginsburgh, 1977; Graen, Novak, & Sommerkamp, 1982; Seers & Graen, 1984). Most of these studies were based on a dual attachment model suggested by Graen & Ginsburgh (1977), in which both job characteristic variables (e.g., task analyzability, skill variety, autonomy, feedback, etc.) and leader-member relationship affect important organizational effectiveness variables, such as job satisfaction and performance. The results of related empirical studies (Dunegan, Duchon, & UhlBien, 1992; Graen, Novak, & Sommerkamp, 1982; Seers & Graen, 1984) are not consistent. While Seers & Graens (1984) study reported that both job characteristics and LMX had a main effect on productivity with no interaction between them, Graen, et als (1982) study found that only LMX was significantly related to job satisfaction and productivity. Noting the inconsistent findings, Dunegan, et al. (1992) hypothesized that job characteristics (i.e., task analyzability and task variety) would moderate the relationship between LMX and performance. Although the -6-

result of their study supported the hypothesis, the interaction was clearly not overwhelming (R2 = .025). The exact relationship between job characteristics and LMX is still left unclear by the research. A closer look is warranted. The basic premise of LMX theory is that developing and maintaining a high quality exchange with subordinates consumes a leaders time, effort, and emotional resources. Since those resources are limited, there will be constraints on the number of high quality dyads a leader can feasibly sustain. Therefore, supervisors will be very cautious about initiating a leader-member relationship (Dansereau, Graen, & Haga, 1975). The LMX studies have been focused on individual factors that affect the relationship development, such as personality (Deluga, 1998; Murphy & Ensher, 1999), liking (Engle & Lord, 1997), similarities (Bauer & Green, 1996; Engle & Lord, 1997; Murphy & Ensher, 1999; Sparrowe & Liden, 1997), trust (Deluga, 1994; Martin, Taylor, O'Reilly, & McLaurin, 1999), personal characteristics (Dienesch & Liden, 1986). The untested assumption underlying these studies is that work environment does not have any restrictive effect on both parties (i.e., supervisor and subordinates) in initiating the relationship based on the personal variables. However, there are several reasons to believe that this assumption does not seem to be reasonable. First, there are a tremendous number of studies showing how work environment affects workers behaviors and attitudes. Strong evidence from empirical studies (e.g., Brain & Raymond, 1985; Brief & Aldag, 1975; Hackman & Lawler, 1971; Hackman & Oldham, 1975, 1976; Lawler, 1970; McCormick, Jeanneret, & Mecham, 1972; Renn & Vandenberg, 1995) based on the job characteristic model supports the idea that job characteristics can directly affect employee attitudes and behavior at work. If job characteristics affect employee attitudes and behaviors at work, LMX, which is said to be initiated based on individuals perception (Engle & Lord, 1997; Sparrow & Liden, 1997), should also be affected by job characteristics. Second, considering the effect of job characteristics on LMX is consistent with a socio-technical system perspective that recognizes that social subsystems (e.g., interrelationship among employees) and technical subsystem (e.g., job design and work environment) are interrelated (Pasmore, 1982). Finally, leadership substitution literature explicitly suggests that some task characteristics can reduce the need of specific types of leadership (Gordon, 1994). Thus, task characteristics may be affecting leadermember relationships. Therefore, considering the effect of job characteristic variables on LMX will enhance our understanding about those situations within which LMX can be facilitated or restricted. In the following subsection, the Hackman & Oldhams (1975) job characteristics typology will be utilized to suggest some possible relationships between job characteristics and LMX. Skill Variety Skill variety refers to the degree to which a job requires a variety of different activities in carrying out the work (Hackman & Oldham, 1976). The effect of skill variety can be considered from both subordinate and supervisors perspectives. If a job requires a subordinate to master various skills, then the subordinate needs more resources (e.g., information, training) and support (e.g., emotional motivation, feedback) from his or her supervisor. This implies that a leader would have more opportunity to exercise his or her influence on the subordinate. As LMX theory suggests, both leaders and subordinates are motivated to invest additional time and effort in the relationship, only if they believe they will receive something of value in the exchange (Dansereau, Cashman, & Graen, 1973; Dansereau, Graen, & Haga, 1975), In the higher skill -7-

variety exchange the member gets help in facilitating ease of job activity and the leader gets higher quality work something of value for each. In addition, the subordinate who get much more resources and support from a leader may feel an obligation to reciprocate for the leaders support (Wayne & Green, 1993) through initiation of more positive interactions. Therefore, Proposition 3: The skill variety of a job will be positively related to the quality of LMX. Task significance & Task Identity Task Significance refers to the degree to which the job has a substantial impact on the lives or work of other people, whether in the immediate organization or in the external environment. Task identity refers to the degree to which the job requires completion of a whole and identifiable piece of work. These two job characteristic dimensions are discussed together here, because the same reasoning seems to be applicable to both of them with relation to LMX. It is expected that if the task significance and/or task identity of a subordinates job is higher, subordinates will be more likely to develop a higher quality of LMX. This speculation is based on two reasons. First, because of the limited resources supervisors cannot keep tack of all their subordinates work. Given that fact, they would not only develop differentiated relationships with different employees, but also be more likely to rely on those subordinates whose jobs are important than others (Dunegan, Duchon, and Uhl-Bien, 1992). Even though this does not negate the possibility of the high quality of LMX between a supervisor and a subordinate whose job is minor in the workgroup, the possibility of high quality LMX development between a supervisor and a focal subordinate doing an important job is more likely just given the attention and concern devoted to that person and job. Second, from a subordinate perspective, if his or her job is important and has significant impact on other people in the same work group or in the organization, or the result of the work is highly identifiable because of high task identity, then the subordinate is more likely to be motivated to perform better (Hackman & Oldham, 1975, 1876). To perform better, the subordinate will try to get more information and resources from all possible sources, including his or her immediate supervisor. Consequently, the subordinate is more likely to communicate with his or her supervisors than other subordinates whose jobs are not significant with this communication facilitating a higher quality LMX relationship. Therefore, Proposition 4: The task significance and task identity of a job will be positively related to the quality of LMX Autonomy Autonomy here refers to the degree to which the job provides substantial freedom, independence, and discretion to the individual in scheduling the work and in determining the procedures to be used in carrying it out (Hackman & Oldham, 1976). With relation to LMX, it is expected that if the autonomy of a job is high, the quality of LMX would be low. The autonomy LMX relationship can best be thought of primarily from the subordinates perspective. If a subordinate is already given enough autonomy by job design, then the supervisor may not be able to give extra autonomy to the subordinate as a job perk. Even if the supervisor could do so, the extra autonomy provided by the supervisor may not be valued or as valued by the subordinate. For example, employees working in flextime system, where they are allowed to set their own working schedule (Ronen, 1981), are less likely to seek extra autonomy through a high quality of LMX relationship than employees working in a traditional work schedule system. This -8-

reasoning is consistent with the underlying logic of LMX, in that subordinates are motivated to develop a high quality LMX with their supervisors, only if they believe they will receive something of value in the exchange (Dansereau, et al., 1973, 1975). If they do not value the extra amount of autonomy given by supervisors, then the need for high quality of LMX is more likely to be low. Furthermore, Autonomy implies, by its very nature, less need for supervision. Employees decides how to do things on their own, so contact with the supervisor is less required. Less contact means fewer opportunities for communication and relationship development. Therefore, Proposition 5: The autonomy embedded in a job will be negatively related to the quality of LMX. Feedback Feedback here refers to the degree to which carrying out the work activities required by the job results in the individual obtaining direct and clear information about the effectiveness of his or her performance (Hackman & Oldham, 1976). With respect to LMX, if a job provides enough feedback about the performance, then the quality of LMX is less likely to be high. The underlying logic of this expectation is similar to that of the autonomy LMX relationship. Since high-feedback subordinates are given enough feedback about their performance from the job itself, then extra feedback from supervisors would be unnecessary. Even if a leader did provide extra feedback, the leaders feedback may not be valued or valued as highly by subordinates, since people tend to value information from objective sources more than that coming from subjective sources (Taylor, Fisher, & Ilgen, 1991). Some leadership substitution research suggests that if a task is clearly defined and well designed with respect to feedback, then employees may neither need nor want social support from the leader (Gordon, 1994). If a job consists of ambiguous tasks with little or no specific feedback imbedded in the task itself, then the employees need the leader's support and feedback. Therefore, Proposition 6: The degree of feedback inherent within a job will be negatively related to the quality of LMX. PERCEIVED SIMILARITY AND LMX As mentioned earlier, most of the antecedents of LMX studied to this point are individual level variables, such as personality (Deluga, 1998; Murphy & Ensher, 1999), liking (Engle & Lord, 1997), similarities (Bauer & Green, 1996; Sparrowe & Liden, 1997), trust (Deluga, 1994; Martin, Taylor, O'Reilly, & McLaurin, 1999), and personal characteristics (Dienesch & Liden, 1986). Although the constructs used in those studies differ from study to study, the bottom line is that the more both parties of a dyad share some similarities, the greater likelihood they will develop a high quality LMX relationship. One question in this area concerns whether or not the similarity should be actual or can be simply a perceived one. Although some studies reported the positive relationship between actual similarities and the quality of LMX, Murphy & Enshers (1999) study, in which both perceived similarity and actual similarity were tested, found that perception of similarity was more important to LMX quality than actual demographic similarity. Several reasons for this relationship between perceived similarity and the quality of LMX have been suggested. First, perceived similarity increases the extent of the mutual affection that the members of the dyad have for each other; thus, the quality of LMX is increased (Liden & Maslyn, 1998). Second, with shared perception of similarities, the possibility that the members -9-

of a dyad may validate each others views of the organization, share a common fate, and enjoy interpersonal comfort would increase. These enhanced factors would in turn increase the chances for a high quality of LMX (Graen & Cashman, 1975). Third, perceived similarity may reduce potential risk related to the development of high quality of leader-member exchange through reduced role uncertainty. Leaders and members in perceived similar situations may be able to more readily infer the expectations that the counterpart might have than those who perceive less similarity. All these explanations appear to be consistent with reinforcement theory, which suggests that people are attracted to those individuals with whom they associate receiving rewards, one of which is similarity (Lott & Lott, 1961, 1974). That is, an individual will be attracted to another person who shares common attitudes and beliefs, because attitude similarity provides evidence of the correctness of the individuals interpretation of social reality (Boyd & Taylor, 1998) perceived similar. Therefore, the perceived similar dyad is more likely to develop a better LMX relationship (Deluga, 1998). From this reasoning, it can be expected that, Proposition 7a: The perception of similarity will be positively related to the quality of LMX. While combining proposition 7a with proposition 1a and 1b suggests that the effect of similarity perception on OCB is mediated by LMX, this does not necessarily exclude the possibility of the direct relationship between perceived similarity and OCB. Some theoretical connections for the direct relationship between perceived similarity and OCB can be drawn from self-categorization theory and from some of the OCB literature. According to self-categorization theory, individuals seek to maintain a positive social identity through self-categorization (Tajfel & Turner, 1986), which may encompass such personal characteristics as age, sex, personality, and the like. This self-categorization leads to the categorization of other people either into the in-group or into the out-group depending on similarity and the focal persons self-identity is anchored within the in-group, which is composed of members with individual characteristics similar to his or her own (Prithviraj, 1999). Since people are motivated to maintain desired positive social identity that is anchored to the in-group, they are motivated to achieve or maintain perceptions of superiority of the in-group over the outgroup (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). This motivation would then be expected to lead the in-group to more OCBs toward in-group members than out-group members, since OCB is a vital factor in maintaining for an organization or a group and making it successful (George & Brief, 1992). Therefore, Proposition 7b: The higher degree of perceived similarity, the more OCB that will be exhibited within the group. CONCLUSION LMX theory has been evaluated to explain the variances in the effect of leadership style on the reactions of subordinates (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). However, LMX may have devalued the effect of work environment, by focusing primarily on the effect of personal variables on the dyadic relationship and by not addressing the role of group dynamics. This conceptual paper has attempted to incorporate two group level variables, group cohesion and work-group task type, as well job characteristics, into the current LMX literature. First, group cohesion is proposed to have two different effects on OCB. While group cohesion has direct positive effect on OCB, it also has an indirect negative effect on OCB through LMX. That is, high group cohesion may actually reduce the quality of LMX, and - 10 -

eventually reduce the OCB. Second, different job characteristics are also expected to have differential effects on LMX and OCB, depending on the type of the dimensions. While skill variety, task significance, and task identity are expected to increase the quality of LMX, and thus increase OCB, autonomy and feedback may decrease both LMX and OCB. Third, perceived similarity is expected to increase LMX and OCB both in direct and indirect ways. Finally, the effect of the quality of LMX on OCB is moderated by work-group task types rather than having a direct linear effect. The relationships between the antecedents of LMX, LMX, and OCB, hypothesized here have several implications. First, the different effects of the antecedents on LMX imply different configurational situations. With the current perspective adopted in LMX literature, in which only perceived personal similarities are considered, it is implied that managers might be highly restricted in developing high quality of LMX relationships to few subordinates whose personal attributes are similar. However, recognizing the effects of job characteristics and group cohesion, managers may have alternative ways to improve the quality of LMX with a focal person who is not similar in personal attributes, for example, by assigning the focal person to a unstructured job, which also requires various skills, and for which task significance and identity is high. Second, since group cohesion may have a negative effect on LMX, while it is expected to have positive effect on OCB, a manager is required to pay attention to the characteristics of group cohesion, especially to the group norms and rules that influence on the members. This implies that if a leader can exercise some influence over the group norms, perhaps by acting as a group member, then the negative effect of group cohesion on LMX can be minimized, if not totally removed. One study shows that if leaders attend to the cohesiveness of their groups, subordinates will value leaders exercise of influence on the group structure, even when the group cohesion is high (Dobbins & Zaccaro, 1986). Third, unlike the current LMX literature that does not consider work-group task type, the recognition of work-group task type provides leaders with one more useful criterion for distributing his or her limited resources in developing LMX. Since high quality of LMX does not always lead to more OCB in all situations, a leader should sense under which work situations his or her resources invested in the development of LMX would bring effective OCB, then employ different LMX development strategies. For example, a strategy whereby a leader tries to develop a high quality of LMX with as many subordinates as he or she can, would be more effective under additive work type situations, than under disjunctive work-type situations. A leader should invest his or her resources in developing high quality LMX with those few subordinates who can do more OCB under a conjunctive work-group task situation. This paper attempts to incorporate several heretofore unexplored but important variables into the current LMX literature as an exploratory step in broadening that literature. Nevertheless, it is obvious that a more comprehensive model incorporating even more variables that affect LMX may be desirable. Also, the current paper includes, for reasons of parsimony only one outcome of LMX that being OCB. However, this does not negate the effect of LMX on other important dependent variables at all. As other studies show, LMX has been shown to have significant effect on various organizational effectiveness variables, such as performance, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, performance appraisal, empowerment, and career progress (see Graen & Uhl-Bein (1995) for detailed references). The only reason that these variables are not included in the current model is that they do not seem to have as strong a relationship with LMX as does OCB. For example, the job characteristic model suggests that job - 11 -

characteristics would have a direct effect on performance as well as an indirect impact through LMX. Also, group cohesion may have a direct or indirect effect on performance, while personal similarity may not have any effect on performance. These different possible relationships imply more complicated models. Future research efforts and theoretical conjecture are required to develop more comprehensive and broader models. It is believed that the current model may facilitate the broadening of theory and ultimately research and practice in this area.

- 12 -

REFERENCE Aldag, R. J., & Brief, A. P. (1977). Relationships between leader behavior variability indices and subordinate responses. Personnel Psychology, 30(3), 419. Bauer, T. N., & Green, S. G. (1996). Development of leader-member exchange: a longitudinal test. Academy of Management Journal, 39(6), 1538-1567. Boyd, N. G., & Taylor, R. R. (1998). A developmental approach to the examination of friendship in leader-follower relationships. Leadership Quarterly, 9(1), 1-25. Brain, T. L., & Raymond, A. N. (1985). A meta-analysis of the relation of job characteristics to job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 70(2), 280-289. Brief, A. P., & Aldag, R. J. (1975). Employee reactions to job characteristics: A constructive replication. Journal of Applied Psychology, 182-186. Cartwright, D. (1968). The nature of group cohesiveness under breaking. In Cartwright, D.; Zander, A., Group Dynamics: Research and Theory (3rd ed., 91-109). New York: Harper & Row. Dansereau, F., Cashman, J., & Graen, G. B. (1973). Instrumentality theory and equity theory as complementary approaches in predicting the relationship of leadership and turnover among managers. Organizational Behavior & Human Performance, 10, 184-200. Dansereau, F., Graen, G. B., & Haga, W. J. (1975). A vertical dyad linkage approach to leadership within formal organizations: A longitudinal investigation of the role making process. Organizational Behavior & Human Performance, 13, 46-78. Deluga, R. J. (1994). Supervisor trust building, leader - member exchange and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 67(4), 315-326. Deluga, R. J. (1998). Leader-member exchange quality and effectiveness ratings: the role of subordinate-supervisor conscientiousness similarity. Group & Organization Management, 23(2), 189-216. Dienesch, R. M., & Liden, R. C. (1986). Leader-member exchange model of leadership: a critique and further development. Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 618-634. Dobbins, G. H., & Zaccaro, S. J. (1986). The Effects of Group Cohesion and Leader Behavior on Subordinate Satisfaction. Group & Organization Management, 11(3), 203-219. Dunegan, K. J., Duchon, D., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1992). Examining the link between leader-member exchange and subordinate performance: the role of task analyzability and variety as moderators. Journal of Management, 18(1), 59-76. - 13 -

Dunegan, K. J., Tierney, P., & Duchon, D. (1992). Perceiving of an innovative climate: Examining the role of divisional affiliation, work group interaction, and leader/subordinate exchange. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 39(3), 227-236. Engle, E. M., & Lord, R. G. (1997). Implicit theories, self-schemas, and leader-member exchange. Academy of Management Journal, 40(4), 988-1010. George, J. M., & Brief, A. P. (1992). Feeling good - doing good: A conceptual analysis of the mood at work-organizational spontaneity relationship. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 310329. Gerstner, C. R., & Day, D. V. (1997). Meta-analytic review of leader-member exchange theory: correlates and construct issues. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(6), 827-844. Gordon, R. F. (1994). Substitutes for leadership. Supervision, 55(7), 17. Graen, G. B. (1976). Role-making processes within complex organizations. In Dunnette, M. D., Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology (Ed., 1201-1245). Chicago, IL: Rand McNally. Graen, G. B., & Cashman, J. (1975). A role-making model of leadership in formal organizations: A developmental approach. In Hunt, J. G.; Larson, L. L., Leadership Frontiers (143165). Kent, OH: Kent State University Press. Graen, G. B., & Ginsburgh, S. (1977). Job resignation as a function of role orientation and leader acceptance: A longitudinal investigation of organizational assimilation. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 19, 1-17. Graen, G. B., & Scandura, T. A. (1987). Toward a psychology of dyadic organizing. In Cummings, L. L.; Staw, Barry M., Research in Organizational Behavior (9, 175-208). Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multilevel multi-domain perspective. Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219-247. Graen, G., Novak, M. A., & Sommerkamp, P. (1982). The effects of leader-member exchange and job design on productivity and satisfaction: Testing a dual attachment model. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 30(1), 109-131. Graham, J. W. (1986). Organizational citizenship informed by political theory Chicago: (Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of Management) Gross, E. (1954). Primary functions of the small group. American Journal of Sociology, 60, 2430. - 14 -

Hackman, J. R. (1992). Group influences on individuals in organizations. In Dunnette, M. D.; Hough, L. M., Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology (2nd Ed. Vol. 3, 199-267). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Hackman, J. R., & Lawler, E. E. (1971). Employee reactions to job characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 55, 259-286. Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1975). Development of the job diagnostic survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, 159-170. Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior & Human Performance, 16, 250-279. Isen, A. M., & Baron, R. A. (1991). Positive affect as a factor in organizational behavior. Research in Organizational Behavior, 13, 1-54. Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1978). The social Psychology of Organizations. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Kidwell, R. E., Mossholder, K. W., & Bennett, N. (1997). Cohesiveness and organizational citizenship behavior: A multilevel analysis using work group and individuals. Journal of Management, 23(6), 775-793. Krackhardt, D. (1992). The strength of strong ties: The importance of philos in organizations. In Eccles, R.; Nohria, N., Networks and Organizations: Structure, Form, and Action (216239). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School. Lawler, E. E., III, Hall, D.T. (1970). Relationship of job characteristics to job involvement, satisfaction, and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 54, 305-312. Liden, R. C., & Graen, G. (1980). Generalizability of the Vertical Dyad Linkage Model of Leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 23(3), 451-465. Liden, R. C., & Maslyn, J. M. (1998). Multidimensionality of Leader-Member Exchange: an empirical assessment through scale development. Journal of Management, 24(1), 43-72. Lott, A. J., & Lott, B. E. (1961). Group cohesiveness, communication level, and conformity. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 62, 408-412. Lott, A. J., & Lott, B. E. (1974). The role of reward in the formation of interpersonal attitudes. In Hutton, T. L., Foundations of Interpersonal Attraction (Ed., 171-192). New York: Academic Press.

- 15 -

Marquis, D. G., Guetzkow, H., & Heynes, R. W. (1951). A social psychological study of the decision-making conference. In Guetzkow, H., Groups, Leadership, and Men (Eds., 5567). Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Press. Martin, D. F., Taylor, R. R., O'Reilly, D., & McLaurin, R. J. (1999). The effect of trust on leader-member exchange relationships in two national contexts. Presented at the Southern Academy of Management Conference. Atlanta, GA. McCormick, E. J., Jeanneret, P. R., & Mecham, R. C. (1972). A study of job characteristics and job dimensions as based on the Position Analysis Questionnaire (PAQ). Journal of Applied Psychology, 56, 347-368. Murphy, S. E., & Ensher, E. A. (1999). The effects of leader and subordinate characteristics in the development of leader-member exchange quality. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(7), 1371-1394. Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome. Lexington, MA: Lexington. Pasmore, W. (1982). Sociotechnical systems: A north American reflection of studies of the seventies. Human Relations, 35, 1179-1204. Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Paine, J. B., & Bachrach, D. G. (2000). Organizational citizenship behaviors: A critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. Journal of Management, 26, 513-564. Prithviraj, C. (1999). Beyond direct and symmetrical effects: The influence of demographic dissimilarity on organizational citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 42(3), 273-287. Renn, R. W., & Vandenberg, R. (1995). The critical psychological states: An underrepresented component in job characteristics model research. Journal of Management, 21(2), 279303. Ronen, S. (1981). Flexible Working Hours. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Book Company. Scandura, T. A. (1999). Rethinking leader-member exchange: An organizational justice perspective. Leadership Quarterly, 10(1), 25-40. Schachter, S., Ellertson, J., McBride, D., & Gregory, D. (1951). An experimental study of cohesiveness and productivity. Human Relations, 4, 229-238. Seers, A., & Graen, G. B. (1984). The dual attachment concept: A longitudinal investigation of the combination of task characteristics and leader-member exchange. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 33(3), 283-306.

- 16 -

Settoon, R. P., Bennett, N., & Liden, R. C. (1996). Social exchange in organizations: perceived organizational support, leader-member exchange, and employee reciprocity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(3), 219-227. Sparrowe, R. T., & Liden, R. C. (1997). Process and structure in leader-member exchange. Academy of Management Review, 22(2), 522-552. Steiner, I. D. (1972). Group Process and Productivity. New York, NY: Academic. Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Worchel, S.; Austin, W., Psychology of intergroup relations (Eds., 7-24). Chicago, IL: Nelson Hall. Taylor, S. M., Fisher, C. D., & Ilgen, D. R. (1991). Individuals' reactions to performance feedback in organizations: A control theory perspective. In Rowland, K. M.; Ferris, G. R., Research in Personnel and Human Resource Management (Eds, 73-120). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press Inc. Uhl-Bien, M., & Graen, G. B. (1992). Self-management and team-making in cross-functional work teams: Discovering the keys to becoming an integrated team. Journal of High Technology Management, 3, 225-241. Van Dyne, L., Cummings, L. L., & Parks, J. M. (1995). Extra-role behaviors: In pursuit of construct and definitional clarity. Research in Organizational Behavior, 17, 215-285. Vecchio, R. P., & Gobdel, B. C. (1984). The vertical dyad linkage model of leadership: Problems and Prospects. Organizational Behavior & Human Performance, 34, 5-20. Wayne, S. J., & Ferris, G. (1990). Influence tactics, affect, and exchange quality in supervisorsubordinate interactions: A laboratory experiment and field study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 487-499. Wayne, S. J., & Green, S. A. (1993). The effects of leader-member exchange on employee citizenship and impression management behavior. Human Relations, 46(12), 1431-1440. Wayne, S. J., Shore, L. M., & Liden, R. C. (1997). Perceived organizational support and leadermember exchange: a social exchange perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 40(1), 82-111. Yukl, G. (1989). Leadership in Organization (2nd Ed.). Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall.

- 17 -

APPENDIX A

Group Group Cohesions Cohesions

Job Characteristics Characteristics Skill Variety Skill Task Significance Task Identity Task Identity Autonomy Feedback Feedback

Group Group Task Type Task Type

OCB OCB

Courtesy Courtesy Altruism Altruism Conscientiousnes Conscientiousnes Civic Virtue Civic Virtue Sportsmanship Sportsmanship

LMX

Perceived Perceived Similarity

Figure 1. A Model of The Antecedents of LMX, LMX, Group Task Type, and OCB

- 18 -

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5795)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Sample Qualitative Research ProposalDocumento6 páginasSample Qualitative Research Proposaltobiasnh100% (1)

- Louis Trolle Hjemslev: The Linguistic Circle of CopenhagenDocumento2 páginasLouis Trolle Hjemslev: The Linguistic Circle of CopenhagenAlexandre Mendes CorreaAinda não há avaliações

- The Glass of Vision - Austin FarrarDocumento172 páginasThe Glass of Vision - Austin FarrarLola S. Scobey100% (1)

- Literacy Term 3 PlannerDocumento10 páginasLiteracy Term 3 Plannerapi-281352915Ainda não há avaliações

- France Culture EssayDocumento3 páginasFrance Culture Essayapi-267990745Ainda não há avaliações

- Grade 8 Pearl Homeroom Guidance Q1 M2 Answer Sheet 2021Documento3 páginasGrade 8 Pearl Homeroom Guidance Q1 M2 Answer Sheet 2021Era Allego100% (2)

- The Science of ProphecyDocumento93 páginasThe Science of ProphecyMarius Stefan Olteanu100% (3)

- 1 IBM Quality Focus On Business Process PDFDocumento10 páginas1 IBM Quality Focus On Business Process PDFArturo RoldanAinda não há avaliações

- Annotated BibliographyDocumento6 páginasAnnotated Bibliographyapi-389874669Ainda não há avaliações

- Love Hans Urs Von Balthasar TextDocumento2 páginasLove Hans Urs Von Balthasar TextPedro Augusto Fernandes Palmeira100% (4)

- What Are The Main Responsibilities of Managers - TelegraphDocumento5 páginasWhat Are The Main Responsibilities of Managers - Telegraphulhas_nakasheAinda não há avaliações

- Practice Test (CH 10 - Projectile Motion - Kepler Laws)Documento7 páginasPractice Test (CH 10 - Projectile Motion - Kepler Laws)Totoy D'sAinda não há avaliações

- Malayalam InternationalDocumento469 páginasMalayalam InternationalReshmiAinda não há avaliações

- Mse 600Documento99 páginasMse 600Nico GeotinaAinda não há avaliações

- Mr. Chu ResumeDocumento3 páginasMr. Chu Resume楚亚东Ainda não há avaliações

- "A Wise Man Proportions His Belief To The Evidence.".editedDocumento6 páginas"A Wise Man Proportions His Belief To The Evidence.".editedSameera EjazAinda não há avaliações

- To The Philosophy Of: Senior High SchoolDocumento25 páginasTo The Philosophy Of: Senior High SchoolGab Gonzaga100% (3)

- Walter Murch and Film's Collaborative Relationship With The AudienceDocumento6 páginasWalter Murch and Film's Collaborative Relationship With The AudiencemarknickolasAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson Plan Cot2 PPST RpmsDocumento2 páginasLesson Plan Cot2 PPST RpmsRhine Crbnl100% (5)

- Integrated Operations in The Oil and Gas Industry Sustainability and Capability DevelopmentDocumento458 páginasIntegrated Operations in The Oil and Gas Industry Sustainability and Capability Developmentkgvtg100% (1)

- A Qabalistic Key To The Ninth GateDocumento70 páginasA Qabalistic Key To The Ninth GateDavid J. Goodwin100% (3)

- LifeDocumento36 páginasLifeMelodies Marbella BiebieAinda não há avaliações

- Yoga Sutra PatanjaliDocumento9 páginasYoga Sutra PatanjaliMiswantoAinda não há avaliações

- Abbreviated Lesson PlanDocumento5 páginasAbbreviated Lesson Planapi-300485205Ainda não há avaliações

- Lesson Plan PbiDocumento7 páginasLesson Plan PbiAzizah NoorAinda não há avaliações

- Operation Research SyllabusDocumento3 páginasOperation Research SyllabusnirmalkrAinda não há avaliações

- Review Desing ThinkingDocumento9 páginasReview Desing ThinkingJessica GomezAinda não há avaliações

- Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan Biograph1Documento3 páginasSarvepalli Radhakrishnan Biograph1Tanveer SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Scarlet LetterDocumento2 páginasScarlet Letterjjcat10100% (1)

- Essay Writing in SchoolsDocumento3 páginasEssay Writing in Schoolsdeedam tonkaAinda não há avaliações