Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

How The Buffaloes Fared in Malaya

Enviado por

Mohamad Zaini SaariDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

How The Buffaloes Fared in Malaya

Enviado por

Mohamad Zaini SaariDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

THE GUNS WOULD NOT FIRE

SECRET REPORT ON NO. 21 AND NO. 453 RAAF SQUADRONS INTRODUCTION 1. For the purpose of clarity this report is divided into three periods, with a Pre-Japanese War Period, the Malayan/Singapore Campaign, and the Post Singapore Period. While there is little cheerful reading in this report it should be borne in mind that the period covered was one when we suffered a set-back, and much of the matter therefore, concerns our inadequacy of the time. THE PRE JAPANESE WAR PERIOD 2. I arrived by air from the United Kingdom at RAAF Station Sembawang on the 4th October, 1941, and after an interview with the AOC [commander], Air Vice Marshal Pulford, I took command of No. 453 RAAF Squadron which was equipped with Buffalo aircraft. Also on the station were the RAAF Headquarters and No. 8 RAAF Squadron (Hudsons) and No. 21 RAAF Squadron (Buffalos). I was amazed to notice amongst many of the Australian personnel on the Station the prevalent dislike that some of them bore for the English--Englishmen were spoken of as "Pommies" with an air of contempt. I did not pay a great deal of attention to this, but it was this that grew into the strong dislike for RAF administration later in the war. It should be noted in turn that RAF personnel elsewhere ostracised the Australians.

3. This matter was aggravated by the obvious and to my mind unwarranted dislike that the Fighter Group controller, Group Captain Rice, had for the two Australian Fighter Squadrons, and

this was later a distinct fillip to inducing a lack of confidence in both Nos. 21 and 453 Fighter Squadrons in the controlling of the air campaign. I believe the crux of this matter lay between my Station Commander, Group Captain McCauley RAAF, and Group Captain Rice RAF, and centred I believe on the question of whose Headquarters should have control of my two Squadrons. Whatever the cause, however, this imposed a strain on me as CO of 453 Squadron and later as Tactical Command[er] of the two Fighter Squadrons, and ... it resulted in Fighter Group Headquarters taking practically no interest in us and our equipment and organisation. It may explain the situation that arose from this, when I say that when we were later expected to operate in defence of Singapore, the Fighter Group were unable to control us at first, because a normal fighter dispersal ops. with telephones, an elementary requirement, had not been laid on. This method of conducting warfare is bound to affect units adversely and is most unfair on the Squadron Commanders, who have enough to do without having to convince regularly both pilots and men that the Higher Command are doing their best. 4. The aircrew personnel of No. 453 Squadron with the exception of the two Flight Commanders, Flight Lieutenant Grace and Flight Lieutenant Vanderfield, were pilots straight from PTS [pilot training school], and some of them told me when I questioned them, that they had no desire to be fighter pilots and had been given no choice in the matter. The officers consisted of two Flight Commanders who had very little experience in operations and very little in Service matters, and also three Pilot Officers who came from the same PTS, and were of the same seniority as the Sergeant Pilots--besides these there were the Adjutant, Flight Lieutenant Wells, and the Engineer Officer, Pilot Officer Pannial. The ground crews were entirely Australian with the exception of nine WT [wireless telegraphy or radio] operators who were ex-RAF. 5. No. 21 Squadron was a regular Australian squadron and was commanded by Squadron Leader Allshorn RAAF. Though I had no control of this squadron until after the war started with Japan, I was responsible for teaching them their fighter tactics and air drill, as none of their pilots had any operational experience. 6. The Pilots of both Squadrons were put through their OT [illegible] Squadron operational training in a remarkably short time. Everyone was extremely keen and the units well knit. On the occasion of the AOC's inspection, Air Vice Marshal Pulford said he was extremely pleased with the advance of the units, and Group Captain McCauley RAAF Station Commander expressed the progress made as an unprecedented personal achievement. I say this because I feel sure Captain McCauley realized the gulf of feeling lying between the Australians and the English that had to be bridged. 7. About six weeks after my arrival in Singapore I realized that war with Japan was highly probable, and I approached the AOC in order to change some of the pilots in my Squadron--I hoped to obtain in place [of them] some experienced officers who were more suited for fighters. I was instructed by him to fly to Australia where I was to try to get some more pilots, unfortunately I was unable to achieve any results and I was told that any available experienced pilots were required to form a Higher OTU in Australia in June of the following year. 8. At this stage the Japanese war commenced and I immediately returned to Singapore.

THE MALAYAN/SINGAPORE CAMPAIGN 9. I returned to Singapore on about the 19th December to find that two thirds of the pilots of the Squadron had been sent to Northern Malaya to assist No. 21 Squadron which had not fared too well on its own. [21 Sq. was caught on the ground on 8 Dec, and when it retreated next day only six aircraft could be made airworthy. Four of these were shot down on 10 Dec.] I was instructed by Group Captain Rice (Fighter Group) to go up and pull the two units together, and I understood from him that the morale of the two squadrons was very poor. (Group Captain McCauley was away on a tour of the Middle East at that period.)

10. I flew up to Ipoh the next day with the remaining pilots and aircraft. I found on arrival that the morale of both Squadrons had dropped. Both units had suffered some losses and the Officer, Flight Lieutenant Vigors who had come from Kallang to command No. 453 in my absence had been shot down in flames on his first sortie. 11. Several matters required immediate attention, but the most serious was the considerable losses we were suffering [to] our irreplacable aircraft, that were being destroyed on the ground, and I decided that if we were to be able to operate at all at the end of another seven days we must stop this heavy drain on our numbers. 12. The landing ground position was disastrous for fighter operations. There was only one landing ground and that was at Ipoh, the surrounding country was jungle, rubber [plantation], or mountainous, and we had no facilities for airfield strip construction. Ipoh airfield consisted of a usable strip with another at right angles to it at the North end, but which was too small for any but the lightest types of aircraft. A narrow Macadam taxi track led off from the usable strip and off this track lay the dispersal pens. However, there were no pens [revetments] and also no other possible means of dispersing the aircraft on the strip itself owing to the Japanese ground straffing

tactics, and our only alternative was to have to the aircraft either in the air or along the taxi track in their dispersal pens as we had no warning system. 13. The taxi track to the dispersal pens was exceedingly narrow and [illegible; I think he's saying they needed an erk to guide each wingtip]; furthermore the aircraft which had become bogged through running a wheel off the track it was necessary for all pilots to excercise extreme care; as many of the pens were a remarkably long way distant at the end of this winding track it was nearly impossible to get a flight or Squadron onto the strip for take-off in less than 20 minutes, by which time it would have been too late to intercept any enemy aircraft. 14. The airfield was located in the valley and if no air cover was in the air while the aircraft prepared for take-off, Japanese fighters or bombers, signalled by spies located in the nearby hills, would attack our aircraft when they were on the ground or taking off. Furthermore almost invariably when our aircraft were landing, Japanese aircraft attacked if no top cover was available, in any case they usually attacked the top cover when it attempted to land. 15. This problem was discussed with Wing Commander Forbes[?] the Officer Commanding NOR Group and I proposed that the only solution to operating from Ipoh lay in some form of warning system. This was agreed and I was instructed to prepare a fighter ops. system. 16. A crude observer system was available which theoretically gave us reasonable cover. However, there were practically no signal specialists available to us, and very little equipment, we had to rely on asking the assistance from the local AA [anti-aircraft artillery] Unit for our telephone equipment. The telephones which literally must have been some of the first that were ever made were totally unreliable. The observer system which I had to use had been organized by fighter ops Kallang, and under it we were unable to get reports on approaching enemy aircraft direct from the observer posts, but got them through the Railway Station Master at Kuala Lumpur. Owing to the delays attendant on this system we usually got our warnings that the Japanese were 40 miles away just as the raid was on. I had with me in the ops. room the Colonel Commanding the local AA Unit and we occasionally got helpful information from him on approaching enemy raiders. Considerable delays were experienced however, through the telephone lines which ran through the jungle being cut either by 5th columnists [Japanese collaborators] of whom there were plenty, or by bombing. 17. As soon as the operations system was completed I tried to instruct the four Flight Commanders so that they could take a turn at controlling in order to relieve me, but they had no knowledge of controlling units and they needed supervision if we were to intercept any raiders. Unfortunately the day after the completion of the ops. system, the Army lost ground and we [lost] our observer posts. 18. During the two days that were necessary to construct the fighter control system, including the provision of a suitable ground station, as there was none up to that time, I arranged for a constant cover of four aircraft from each of the two Squadrons throughout daylight. This was expensive as we anticipated, on engine hours, but as we were not attacked once during that period it gave us two days valuable respite in which to reorganise and repair the aircraft. 19. The need for reorganisation was considerable. The Aircraft of the two Squadrons were being serviced by the ground crews of only No. 21 Squadron [since only the aircraft of 453 Sq. had moved up to Ipoh]. This Unit's ground crew strength was totally inadequate for one Squadron, let alone two, and the vast majority of guns in the aircraft would not fire, because of the rust which

the troops had not had time to clean off. I had signalled to Singapore for Armourers from my own Squadron as soon as I had reached Ipoh, and these men had arrived before we retreated from the airfield, and had improved the guns considerably before we left. Inspections were also not being done and the aircraft were rapidly becoming unreliable. The ex civil Airline engines on the Buffalos were quite unsuited to the treatment they were getting in combat and on the ground, and many developed serious loss of [illegible, but probably intending "loss of oil" or "loss of power"].

UNFIT FOR SUSTAINED OPERATIONS 20. The reorganisation of the Station was also a serious and pressing problem. There was no appointed Station Commander. Food was an urgent need--the men were going without food and so were the pilots. There was no suitable accommodation and as the men and pilots were sleeping without mosquito needs under any available covering I feared malaria. 21. I therefore requisitioned accommodation in a Hotel at Ipoh and sent out the cooks with money to buy food, and I also tried to introduce certainty and reliability into the organisation so that morale should be improved. 22. Transport was lacking at first and caused grave difficulties. Spare parts for aircraft were usually obtained by the cannibal system, oxygen was not available. Neither 21 Squadron nor 453 Squadron were equipped with either men or equipment for the role they were given, and while expected to be self supporting they had neither trained cooks. MT [motor transport], nor sufficient specialist staff or equipment to do their duty as they would have liked to do it. Furthermore nearly all native labour on which we had to rely, had disappeared when the war

became "dangerous." I believe from hearsay that these circumstances were foreseen by the RAAF Headquarters at Sembawang sometime before the war started, and a proposal put up by them to substitute RORs [?] for native labour was turned down. 23. My conclusions from the foregoing matters at Ipoh were that there was a lack of imagination in the prewar preparations made for Air Warfare in this area, and this resulted in a lack of air support for the Land Forces and in both No. 21 Squadron and 453 Squadron being forced into a state where they were unfit for sustained operations against the enemy. 24. While I was at Ipoh there was only one minor air combat and no land support operations were requested by Group Headquarters. ON the 20th December evening, the day on which our observer system fell to the Japanese advance troops, we received instructions to retreat to Kuala Lumpur at first light the following morning. Transport was "borrowed" but considerable difficulty was experienced through the night in preparing for the move, as we even lacked torches and the airfield was completed blacked out through lack of any form of lighting. Fortunately a crash and Repair Unit (also retreating I believe) reached us that evening and they were able to assist considerably with breaking up crashed aircraft and removing all value and transportable parts including engines. 25. On the 21st morning I flew with the pilots of 453 Squadron to Kuala Lumpur; it has been arranged for 21 Squadron pilots and ground crew to return to Sembawang to reorganise and for me to have my own ground crews from Singapore. 26. Kuala Lumpur airfield was a single strip which was being partly reconstructed. There were no dispersals and we had the aircraft spread out around the strip and covered with branches from trees. The ground crews with tankers [petrol bowsers or gasoline trucks] did not arrive until later that day, and no operations were carried out. An Operations room and warning system were again in the course of being formed but were not ready in time to control us successfully by the time we left for Singapore on the morning of the 24th. It did not seem at first that there was every chance of our being able to get down to some regular operations from Kuala Lumpur. The Japanese ground troops were about 100 miles away and I anticipated that we had 10 clear days at least in which to operate. No. 453 Squadron was similar to No. 21 Squadron, in that it was also not equipped satisfactorily for a Squadron expected to be self supporting in this theatre, there no cooks, no MT other than petrol tankers, and no MO or Intelligence Officer. Our first task was to get the aircraft fully servicable and to utilize our troops so that the Squadron was on a working basis with facilities for food and accommodation. The Group ops organisation had been placed in the hands of an experienced officer, Wing Commander Daley, and we were fortunately comparatively free of duties in connection with its functioning. 27. Only two operations took place during the three days we were at Kuala Lumpur. On the first occasion our aircraft were attacked as they were taking off, and in the second they were attacked from above just as they had formed up after take-off. In these two combats we lost three pilots killed, four wounded, and six aircraft written off from our remaining strength of 14 aircraft and pilots ... having lost five pilots killed and wounded and several aircraft at Butterworth and Ipoh before my arrival. No true record was available of the numbers of enemy aircraft shot

down by the Squadron but we later heard indirectly from the Army that the wreckages of 25 Japanese aircraft were found around Kuala Lumpur. 28. On December 23rd, instructions were passed to us to return to Sembawang on the following morning. This was done.

29. On my return to Singapore a reorganisation of both 21 Squadron and 453 Squadron took place. Squadron Leader Allshorn, CO of 21 Squadron, was replaced by Flight Lieutenant Williams RAAF, who became Squadron Leader Commanding that Unit. On my recommendation Flight Lieutenant Kinninmont RAAF, ex 21 Squadron, took over 453 from me. This enabled me to leave all the administration and to lead both Squadrons of whom I was given tactical control. Owing to Flight Lieutenant Kinninmount's inexperience, Flight Lieutenant Wells the Adjutant of 453 Squadron was instructed to look after the administration of the men of that Unit. 30. The Buffalo aircraft with which both Squadrons were equipped were slow and less manoeuvrable than the Japanese aircraft with whom they came in contact, and who outnumbered them considerably. Before the Japanese war had started we were given no useful intelligence information on the enemy aircraft, the only information made available to use were some silhouettes of early Japanese biplanes, which resulted in both Units going into battle with a very wrong impression of the opponent they were going to meet. This was a very serious matter as it completely upset all the tactics that had been planned, thereby giving the enemy Air Force the initiative. Our pilots could not dog fight nor use dive and zoom tactics, and expect to get the better of the enemy fighters, who also had an appreciable advantage in the climb owing to their better power to weight ratio. A further serious setback was that above 14,000 feet the pilots had to pump his petrol to his engine continually by a hand pump if he wished to use more than about half throttle setting; this state of affairs made air combat a very uneven match.

31. I had decided at Kuala Lumpur to reduce the disadvantages of the Buffalo as much as possible, and on my return to Singapore I arranged for all aircraft to be stripped of as much surplus weight as possible. By reducing the petrol load and ammunition and replacing two of the four .5 guns with .303, we reduced the load by almost 900 lbs, thereby improving the performance in combat appreciably. However, not all aircraft were modified as there was a considerable amount of normal work to be done and we had no assistance beyond our ground crews. 32. Several good sorties were carried out on bomber escort and ground straffing duties. 33. During January 1941, the aerodrome was bombed a few times by formations of Japanese bombers who dropped many medium size bombs. This bombing was reasonably accurate and though our aircraft were in their pens or dispersed around our portion of the aircraft we lost many of them. This was infuriating as we felt we ought to be in the air before these raids came. A radar warning system was being operated by fighters ops at Kallang but we were not called on [line evidently missing] have handed them to the Japanese on a plate. The role of the two Squadrons was changed several times from that of Army Support to pure fighter interception, however we were somehow never on our fighter role when the Japanese were bombing the Island which was done fairly regularly. The main task of the squadron on most days seemed to be to send two aircraft out each morning as a recce. [reconnaissance] for the Army. I was several times approached by the pilots who spoke in a manner showing they had little confidence in the RAF's ability to run its affairs, and they were opening in favor of moving nearer to Australia so they could come under Australian control and put up a better fight. While there may have been considerable wisdom in what the Australians said, my orders were to get on with the job. At Kuala Lumpur for example I had a considerable disagreement with Flight Commanders who considered we ought to return and operate from Singapore under a reasonable working fighter control system, rather than lose our aircraft in penny packets for little apparent result at Kuala Lumpur. My orders, however, were to stay there and in supporting my superiors I made myself extremely unpopular with my Squadron. This was a very unenviable position for me to be in, and as these circumstances repeated themselves before the campaign was over I do believe the troops felt I was in league against them. 34. It may show the extent to which the dislike of the Royal Air Force was prevalent when I saw that it was necessary for the Station Commander, Group Captain McCauley, to assemble his officers before him and instruct them to cease drawing comparisons between the two Services [between the RAF and the RAAF, presumably]. 35. After the war with Japan had commenced, work had been started to make dispersals for aircraft and the ground organisations in the rubber [plantation] away from the airfield. This made it difficult to keep an eye on the troops during raids, and Pilot Officer Pennial the Engineering Officer of 453 Squadron reported that he was finding difficulty in locating men to work on the aircraft. I found that some men were going off to their billets and into the woods and were not being stopped. I therefore let Flight Lieutenant Kinninmount lead the flying and [I] commenced to organise the men again in No. 453. Parades with roll-calls were organised throughout the day and I instructed Flight Lieutenant Wells to arrange a system whereby certain

reliable NCOs were given approximately 15 men and they were responsible that their men kept at work. This did not prove entirely satisfactory as some of the NCOs were as lackadaisical as some of the men. Great difficulty had been experienced throughout in trying to develop a sense of responsibility and importance of position in the Officers and NCOs. There were no Warrant Officers and only two Flight Sergeants in the whole Squadron, one of whom Flight Sergeant [evidently a phrase missing]. Discipline was extremely weak, and the remaining Sergeants and Corporals had risen from amongst the men with rather mushroom-like speed, and too many of them were not satisfactory from the disciplinary aspect. 36. I had occasion to speak severely to Flight Lieutenant Wells who would not support me in making the men get to reasonably near shelter trenches in an air raid. He contended that they should be allowed to go to trenches some distance away, if they liked. This gave a bad lead to the NCOs and owing to the shortage of other officers I had to go around the dispersal points myself to ensure my orders were being obeyed. It was not practicable to obtain an exchange for Flight Lieutenant Wells at this stage, owing to the difficulty of obtaining an Adjutant who could take over immediately.

37. Towards the end of January, the two Australian GR [reconnaissance?] Squadrons who were now located at Sembawang, plus No. 21 Squadron, retreated from Singapore to Sumatra. The Station was placed under RAF control with Group Captain Whistondale as Station Commander. This officer was eccentric and often spent time discussing his hobby of stamp collecting with the

airmen, when the Station organisation was in urgent need of assistance [The sentence was lined out]. At the same time as this change, all the remaining Buffalo aircraft in Singapore from the other Squadrons were given to me along with an assortment of pilots. A Fighter ops dispersal organisation had been set up, and we were now fully under the control of Kallang fighter ops. The aircraft we had been sent, however, had already been well used by other units and they required considerable checking and servicing in every case except one before we could operate them. Furthermore with the departure of all the RAF personnel except for one or two officers of the Headquarters Staff, and those of course of No. 453 Squadron, no RAF troops had been brought in, and out of a Squadron of 150 men we were forced to provide 50 for manning the Station. Some of the men worked extremely well and creditably although we were so short handed, but others were not so good, and we often had difficulty in finding them. I had, in fact, on one occasion to ask the AOC to assist me by talking to the troops. 38. As the aircraft were made reasonably servicable, they were tested, and it was found that a large proportion of the Cyclone engines were suffering from a serious lack of power. Spare engines were no available and the number of aircraft therefore available for operational work never exceed six, though there were several more flyable. The enemy had a constant fighter patrol five miles North of the aerodrome, and the controllers at Fighter Group refused to send pilots up [to intercept]. This was a form of stalemate, no policy was given for some while to the Squadron, and they stayed at readiness with no hope of flying. In fact, before one raid they were told by Fighter Control to clear off the aerodrome, as there was a raid coming. I was at this stage unable to tell the Flights what was required of them except to carry on and make the aircraft servicable. These matters were not well received, and the Flight Commanders had, understandably, no enthusiasm in the running of their Flights. 39. On the 4th of February occurred the occasion when half a dozen men of No. 453 Squadron were found some distance from the aerodrome without permission, by Air Vice Marshal Maltby, and it was also the occasion when Australian officers had spoke disrespectfully to the Provost Marshal in front of the troops. At approximately ten o'clock on that day I had gone to the Mess to bath[e] and change, when the enemy commenced to shell the aerodrome and buildings from across the Johore Straits. As the shelling continued, and shells were bursting about thirty yards away, I circumnavigated the Mess and made my way to the Guard Room. I learned here from the Engineer Officer that instructions had come through to fly all aircraft off the aerodrome to Tengah a few miles away, in order to avoid the shelling. A driver was sent round in a van to pick up the pilots from their dispersal; meanwhile, along with the few pilots present, I flew an unserviceable Hurricane belonging to 232 Squadron to Tengah, as it would have been left on the airfield owing to a shortage of Hurricane pilots. Altogether ten aircraft were flown off the aerodrome by my pilots under shell fire. Two aircraft were hit in taxying, and one pilot was hit and blown out of his aircraft by a salvo of three shells. Shortly after the first pilots landed at Tengah , that aerodrome, which was an equal distance from the enemy artillery at Sembawang, also came under fire, and the pilots had then to be asked to start their aircraft and fly them out to Kallang. It was difficult to keep the pilots and crews confident in the command when pilots are asked to fly out of one aerodrome being shelled into another an equal distance from the source of shelling.

40. I was detained for the remainder of the day by Group Captain Rice of the Fighter Group, who had order a Court of Inquiry to be held because our Squadron pilots were late at readiness that morning. [Handwritten note: He canceled that decree later that evening.] I was therefore away the whole day and had no opportunity to control the Squadron and ground troops which were, in my absence, under the control of Flight Lieutenant Wells the Adjutant. I had no idea that any of the men had gone down the roads towards Singapore town, and the first intimation I had that Australian officers had spoken disrespectfully to the Provost Marshal in front of the men was from Air Vice Marshal Maltby himself in Java.

I COULD NOT UNDERSTAND HARPER'S ATTITUDE 41. I found out in Java that two of the men who were concerned in the departure from the airfield to Singapore, were individuals who were mentally unbalanced and had been under observation by the Station Medical Officer for some time, and they most probably influenced the other four who were with them. With regard to the occasion concerning the Provost Marshal, I question my [illegible line] 42. Early in February [1942] we were instructed that the squadron ground crews were to stay at Singapore and fight with Ground Arms--all aircraft which could fly were to go to Palembang in Sumatra. I instructed Flight Lieutenant Kinnimont to take the aircraft and their pilots to Sumatra and I remained with my ground troops. There was some feeling among the men at this order [because they considered?] this was a case of misemployment of trained personnel, and again in supporting my superiors I made myself unpopular. I quote an extract from a Court of Inquiry which was held in Australia on the subject of No. 453 Squadron in 1942, which will, perhaps, explain the situation:

Evidence by Flight Lieutenant Kinninmont RAAF in answer to questions by the court: "I could not understand Squadron Leader Harper's attitude at all. He had a queer attitude towards the whole thing, and did not seem worried whether the Squadron left Singapore or not. I could not understand Squadron Leader Harper's attitude at all in the end, but he had the Squadron in sections ready to defend the aerodrome and more or less fight with the Army.... I think his attitude was more or less the attitude of the British Command there to fight to the end and die for Singapore, or just stay there and be killed. However, he looked after the troops very well, he was always trying to organise things and get decent food, and also arrange sleeping quarters, and with the pilots he was always trying to get them a day off and that sort of thing. He always briefed us properly before the job right to the end, he treated the Squadron very well including men and pilots. Towards the end when it was hopeless and only a matter of a day or two, he did not seem concerned whether the Squadron got away on a ship, and she chaps were prepared to stay although they could not have done any good had they stayed, because they had few arms, about four or five Tommy guns and few rifles, and that was what annoyed the chaps as they could see no good reason why they were staying there to be killed or taken prisoner." The last part of Flight Lieutenant Kinnimont's statement is partly incorrect. We had more arms than Flight Lieutenant Kinnimont has said, and the men were rather resigned to staying on the Island than prepared. However, when the troops were reconciled to it, considerable effort was put into preparing the ground defences; machine guns were taken from crashed aircraft and mounted on tripods made out of parts of crashed Blenheim air frames, and the men were armed and prepared in squads. Arrangements were also made of the men to be led by trained Army Officers in the event of any hand to hand fighting. 43. On the afternoon of the 5th February, contrary to expectation, we were given orders to embark at Singapore and to go to Java. I believe this information was available before but had not been given until the last possible minute as a corrective measure for the troops. Actually it resulted in us not being able to leave our sections as tidily as we hoped and I apologised to Group Captain Whistondale for this. POST SINGAPORE PERIOD 44. We reached Java aboard the Cruiser Danae on the 9th February, and the Squadron was billeted at Buitenzorg Transit Camp. I reported to the RAF Headquarters in Batavia and was given a billet with a Squadron Leader McKenzie in a local private house. I was anxious however to get the Squadron on its feet and operational. All the Buffalos we had sent to Palembang had been destroyed with the exception of two, which were now located at an airfield near Batavia. 45. I approached the Dutch Divisional Staff Headquarters and persuaded them to leave me have some transport so that I could get to Buitenzorg and Bandoeng. 46. Considering the circumstances the Squadron was reasonably housed at Buitenzorg and they were given a good rest. I meanwhile proceeded to Bandoeng ABDAIR [probably meaning the Air section of the American-British-Dutch-Australian command] to try and find out what was happenings and to see if I could get some aircraft. I paid three visits to ABDAIR and spoke to Air

Commodore Williams and Group Captain Roberts, but I could get no definite orders for my Squadron nor any promise of aircraft. 47. On about the 17th February, Air Vice Marshal Maltby instructed me to return to the Unit as he now had matters in hand and had taken over control. 48. Previous to Air Vice Marshal Maltby's instruction to me, I had been approached by the Adjutant, Flight Lieutenant Wells who said the men were very keen to rejoin the RAAF. He said he wanted to visit some RAAF people whom he knew at ABDAIR to enquire if this was possible. I said I had no objection as long as I knew what transpired and all arrangements must be made through me. On his return from ABDAIR I gathered that he had been negotiating to get the Squadron back to Australia, though I had no proof of this. Shortly after Air Vice Marshal Maltby's instructions to me I was again approached by Flight Lieutenant Wells to go to ABDAIR, but I refused him permission this time. He then said that he was expected to go by the RAAF authorities there, but I told him that he must telephone them and explain the situation. He telephoned Wing Commander [blank] of the RAAF who instructed him to go and see Group Captain McCauley, who had arrived from Sumatra. I refused to agree to this however, and spoke to Wing Commander [blank] telling him clearly that the Unit was now under Air Vice Marshal Maltby's control and I refused to take instructions which did not emanate from him. His reply was, "We can soon stop this nonsense". I warned Flight Lieutenant Wells not to leave camp; however, acting on the Wing Commander's orders he reported to Group Captain McCauley. I immediately telephoned Air Vice Marshal Maltby who said he would visit us the next day, but that afternoon I received instructions from the RAF, through the Camp Commandant, to embark my Squadron at Batavia and to go with it. This was done and we reached Colombo on the 27th February. 49. At my own requst I was kept at Colombo to organise the fighter defences for the Island as an attack by the Japanese was expected. 50. Among the personnel of the Squadron, Pilot Officer Pennial, RAF Engineer Officer, and the Armourer Sergeant Haines RAAF, did outstandingly good work in exceptionally trying and often hazardous conditions, and are very worthy of reward. [signed] W.J. Harper, S/L Air Ministry Branch [illegible] 14 Jan. 1946

Brewster F2A Buffalo From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Brewster F2A Buffalo was an American fighter aircraft which saw limited service early in World War II. It was one of the first U.S. WWII Monoplanes with an arrestor hook and other modifications for aircraft carriers. It usually had an open canopy. Though the Buffalo won a competition against the Grumman F4F Wildcat in 1939 to become the US Navy's first monoplane fighter aircraft, it turned out to be a big disappointment.

Several nations, including Finland, Belgium, Britain and the Netherlands, ordered the Buffalo to bolster their struggling air arms, but of all the users, only the Finns seemed to find their Buffalos effective, flying them in combat with excellent results.[1] During the Continuation War of 1941 1944, the B-239's (a de-navalized F2A-1) operated by the Finnish Air Force proved capable of engaging and destroying most types of Soviet fighter aircraft operating against Finland at that time, achieving, in the first phase of that conflict, a kill-ratio of 32:1, 32 Soviet aircraft shot down for every B-239 lost[2] and producing 36 Buffalo "aces".[3] When World War II began in the Pacific[4] in December 1941, Buffalos operated by both British Commonwealth (B-339E) and Dutch (B-339D) air forces in South East Asia suffered severe losses in combat against the Japanese Navy's Mitsubishi A6M Zero and the Japanese Army's Nakajima Ki-43 "Oscar". The British attempted to lighten their Buffalos by removing ammunition and fuel and installing lighter guns in order to increase performance, but it made little difference.[4] The Buffalo was built in three variants for the U.S. Navy, the F2A-1, F2A-2 and F2A-3. (In foreign service, with lower horsepower engines, these types were designated respectively, B-239, B-339, and B-339-23.) The F2A-3 variant saw action with United States Marine Corps (USMC) squadrons at the Battle of Midway. Shown by the experience of Midway to be no match for the Zero, the F2A-3 was derided by USMC pilots as a "flying coffin."[5] The F2A-3, however, was significantly inferior to the F2A-2 variant used by the Navy before the outbreak of the war.

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Report by General Wavell On Operations in Malaya and SingaporeDocumento26 páginasReport by General Wavell On Operations in Malaya and SingaporeMohamad Zaini Saari100% (1)

- Wing Bug - Flight InstrumentDocumento8 páginasWing Bug - Flight InstrumentDeepak JainAinda não há avaliações

- The Serious Crimes of HCM & The VCP Against The Vietnamese PeopleDocumento306 páginasThe Serious Crimes of HCM & The VCP Against The Vietnamese PeopleTuấnNguyễn100% (1)

- British Army Forces in Malaya 3 September 1939Documento3 páginasBritish Army Forces in Malaya 3 September 1939Mohamad Zaini SaariAinda não há avaliações

- The Schools of Malaya - Frederic Mason 1959Documento25 páginasThe Schools of Malaya - Frederic Mason 1959Mohamad Zaini SaariAinda não há avaliações

- Malaysia's Post-Cold War China Policy A ReassessmentDocumento33 páginasMalaysia's Post-Cold War China Policy A ReassessmentMohamad Zaini SaariAinda não há avaliações

- Operational Art in The Success of The Malayan CampaignDocumento20 páginasOperational Art in The Success of The Malayan CampaignMohamad Zaini SaariAinda não há avaliações

- ACADEMY - Bonded for Life: ArrivalDocumento238 páginasACADEMY - Bonded for Life: ArrivalkrishnaAinda não há avaliações

- Integration of Junagadh: - Junagadh Was A Princely State of India, Located in What Is Now GujaratDocumento72 páginasIntegration of Junagadh: - Junagadh Was A Princely State of India, Located in What Is Now GujaratFIZA SHEIKHAinda não há avaliações

- ArcheryDocumento20 páginasArcheryNiLa UdayakumarAinda não há avaliações

- Kill Team List - Inquisition v7.1Documento9 páginasKill Team List - Inquisition v7.1Koen Van OostAinda não há avaliações

- Bullettest Tube ArticleDocumento3 páginasBullettest Tube ArticleRedmund Tj HinagdananAinda não há avaliações

- ATMIS Begins Phase Two of Troop Withdrawal - Hands Over Bio Cadale FOB To Somali National ArmyDocumento5 páginasATMIS Begins Phase Two of Troop Withdrawal - Hands Over Bio Cadale FOB To Somali National ArmyAMISOM Public Information ServicesAinda não há avaliações

- Gutamaya BrochureDocumento5 páginasGutamaya BrochureokenseiAinda não há avaliações

- Special Zone Sectors 2Documento21 páginasSpecial Zone Sectors 2FinkFrozenAinda não há avaliações

- FM 2-0, With Change 1Documento210 páginasFM 2-0, With Change 1"Rufus"Ainda não há avaliações

- Starkville Dispatch Eedition 8-13-17Documento28 páginasStarkville Dispatch Eedition 8-13-17The DispatchAinda não há avaliações

- Jeler Grigore Romana Forma EnglezaDocumento7 páginasJeler Grigore Romana Forma EnglezaGrigore JelerAinda não há avaliações

- P200 PDFDocumento20 páginasP200 PDFMohamed AliAinda não há avaliações

- FA Doctrine and OrganizationDocumento93 páginasFA Doctrine and OrganizationGreg JacksonAinda não há avaliações

- Instructions For Mbbs Bds 2022Documento5 páginasInstructions For Mbbs Bds 2022Bhargav neogAinda não há avaliações

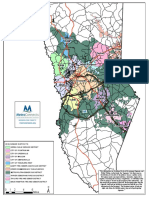

- Metro Connects Service Map As of 2016Documento1 páginaMetro Connects Service Map As of 2016AnnaBrutzmanAinda não há avaliações

- French Indochina HistoryDocumento1 páginaFrench Indochina HistoryasdfAinda não há avaliações

- Prologue Magazine - A Voyage Into HistoryDocumento1 páginaPrologue Magazine - A Voyage Into HistoryPrologue MagazineAinda não há avaliações

- 1903 - Family History John Holbrook EstillDocumento164 páginas1903 - Family History John Holbrook EstillDongelxAinda não há avaliações

- 2008 May-1 PDFDocumento24 páginas2008 May-1 PDFShine PrabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- Lewis Machine ToolsDocumento18 páginasLewis Machine ToolsEugenio Brückmann100% (1)

- The Key To Immediate Enlightenment - in MalayalamDocumento143 páginasThe Key To Immediate Enlightenment - in MalayalamscribbozAinda não há avaliações

- UNICEF Works to End Child Soldier Recruitment in CameroonDocumento3 páginasUNICEF Works to End Child Soldier Recruitment in CameroonNadya AlmaAinda não há avaliações

- Battle of Qadisiyyah: Muslims defeat Sassanid PersiansDocumento22 páginasBattle of Qadisiyyah: Muslims defeat Sassanid PersiansMustafeez TaranAinda não há avaliações

- Conflict Prevention: Ten Lessons We Have Learned, Gareth EvansDocumento13 páginasConflict Prevention: Ten Lessons We Have Learned, Gareth EvansGretiAinda não há avaliações

- 5e A Better Character Sheet (A4)Documento12 páginas5e A Better Character Sheet (A4)Noel Thanbutr HuangthongAinda não há avaliações

- Sony LDM-G1000 Protocol and Command Manual For Sony LDP Series Videodisc PlayersDocumento66 páginasSony LDM-G1000 Protocol and Command Manual For Sony LDP Series Videodisc Playersherrflick82Ainda não há avaliações

- EAU - Adventurer's 1-4Documento4 páginasEAU - Adventurer's 1-4WILLIAM ALBERTO BETTIN SANCHEZAinda não há avaliações

- US V RuizDocumento2 páginasUS V RuizCristelle Elaine ColleraAinda não há avaliações