Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

HIV Project

Enviado por

Michael S. PetryDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

HIV Project

Enviado por

Michael S. PetryDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

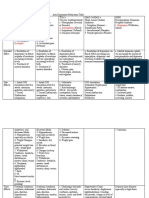

HIV: Research & Nursing Objectives

HIV: Research & Nursing Objectives By Michael S. Petry Gateway Community College

HIV: Research & Nursing Objectives

Abstract This paper examines the origins, transmission and general function of the HIV virus. It also provides an overview of nursing considerations for the HIV/AIDS patent It examines the present treatment considerations and looks at the current trends and obstacles for HIV vaccine research.

HIV: Research & Nursing Objectives

HIV is infecting 5 million people worldwide every year. In the U.S. alone this is estimated at nearly 60,000 new infections each year. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010) As nurses, we are told to treat every patient as potentially HIV+. But there is much more that we can do. HIV/AIDS is no longer merely a health issue. It is a political, social, educational and even economic issue. We appear to be far from a cure or vaccine and as nurses we need to include HIV/AIDS as part of our routine patient education. HIV is the virus that causes AIDS. It is suspected that this virus jumped from a simian species to humans around the turn of the twentieth century. Physical evidence in the form of infected human tissue is available dating back to 1959 with other suspected cases as far back as 1930. (AVERT, 2010) It reached epidemic proportions in the early 1980s in the U.S. affecting mostly young gay men, hemophiliacs and IV drug users. It has spread worldwide to every country and there is no known cure or vaccine. All viruses need a host to survive. They invade cells in order to replicate. HIV is a retrovirus, meaning it contains RNA (as opposed to DNA) as its genetic material. Some viruses, particularly new viruses that jump species like HIV, called non-equilibrium viruses (Baltimore, 2004) are particularly lethal. Not having adapted to the new host, it often kills the host making it sometimes difficult to spread. HIV is such a virus that attacks, primarily, cells of the immune system. It can lie dormant for many years making it particularly lethal as it is spread from person to person. HIV is spread via blood, semen, vaginal fluids and breast milk. There is no evidence that it is spread via tears, sweat, saliva, urine or feces. Once a person is infected, HIV attaches to certain white blood cells, particularly lymphocytes, which act as warriors in our defense against invaders. Our body has natural defenses, such as skin, oils, gastric juices or hairs that work to

HIV: Research & Nursing Objectives

protect us from outside invaders, but once inside our immune system creates antibodies to seek out and kill or render useless invading viruses or bacteria. HIV is particularly well suited to attack one particular immune system cell, T-helper cells, or CD4s. The outer surface of the HIV virus is studded with proteins called gp120. This protein attaches to receptors on T-cells, activates them in a reaction that allows the HIV virus to inject the RNA and proteins it carries within. The HIV RNA uses the proteins and the cells DNA to replicate itself and bud out of the cell, moving on to attack another. Eventually, and often, the cell is destroyed in this process after successfully replicating millions of new virus molecules. In a person infected with the virus, lab tests can determine the viral load, or how many molecules are present in the body, and the CD4 count. A typical CD4 count can vary from person to person, day to day. A normal range is typically between 500 and 1600. But these cells typically can survive many years in a person. As the immune system is slowly compromised, the person becomes more and more susceptible to diseases or infections. When enough CD4s are destroyed to bring that count down to 200, the immune system is significantly challenged and the person is diagnosed with AIDS. An AIDS diagnosis can also be determined by the acquisition of specific infections or diseases opportunistic infections that are prevalent in a compromised immune system. Typically when a persons CD4 level is lower than 350, a doctor will prescribe antiretroviral treatments or ARVs (AIDSInfoNet, 2010) Studies show that the earlier a person is diagnosed, the greater their chance for success with treatments. Once an immune system is severely compromised, it is extremely difficult to recover. Initial infection within 6-12 weeks can include flu-like symptoms such fevers, chills, night sweats, swollen lymph nodes and rashes that last for a week or two. This occurs when the virus enters the body and begins to attack various immune system cells. Often these symptoms

HIV: Research & Nursing Objectives

are missed as an HIV infection because they are attributed to the flu. After about 3 to 8 weeks, our body develops antibodies which make it then possible to test for infection. Many HIV+ persons can experience little to no symptoms for years, yet they are still infected and can still pass the virus on through body fluids. A person can appear perfectly healthy. As nurses, being familiar with the symptoms of HIV infection and the various complications of AIDS is critical to the patient. Our most effective tool is prevention through education. Subsequent to infection, we must be aware of the disease process and interventions at various stages. Risk for anxiety, depression and spiritual distress are always present. As the disease progresses, or as antiretroviral medications are introduced, there are many areas where the nurse can be helpful in improving patient well-being and education. There is increased risk for infection, increased risk for fluid imbalances or imbalanced nutrition, and many drugs cause serious electrolyte imbalances. HIV/AIDS has become a chronic, treatable illness. We need to continue to be a patient advocate, assist in symptom monitoring and management. One critical factor that cannot be over-emphasized is strict adherence to medication schedules. Many HIV medications must be taken at specific times, under specific circumstance (ie., before or after meals) and failure to do so can have severe consequences. Failure to adhere can create a resistance to the treatment. And there is a very limited number of treatments available. Additionally, patients must be clearly educated on prevention practices. We hope to have a vaccine ready for testing in about two years, said Health and Human Services Secretary Margaret Heckler in 1984. This was immediately following the discovery of the HIV virus. But that was 26 years ago and many say we are no closer to a vaccine or cure. While our knowledge about HIV and viruses has swelled dramatically, the more we discover, the greater the challenge seems to become. It is clear that previous ways of creating a vaccine will

HIV: Research & Nursing Objectives

not work with HIV. It was 47 years from the time of the discovery of polio until a vaccine was introduced. Measles was 30 years. The FluMist Nasal vaccine took 27 years. (Dina Kovarik, 2009) It was clearly overly optimistic to think we could develop a vaccine in two years. Treatments for HIV presently take aim at various stages of the lifecycle of the virus. Some individuals seem to me immune to getting the virus because they lack or have an altered CCR5 receptor preventing the virus from entering the cell. Other individuals who are infected have never developed AIDS. It appears that these long-term non-progressors are able to limit the infection because of CD8 cells or other unknown reasons. Current treatments include drugs that inhibit some or all of the proteins that the virus needs to replicateprotease, integrase and reverse transcriptase. Many of the newer drugs available provide a combination of drugs that inhibit these proteins. The viruss ability to mutate makes treatment difficult, however, as it continues to find ways to survive. AIDS patients can eventually develop resistance to therapies. As there are only 30 drugs available presently, and many work in the same way, developing a resistance to any one of them presents new challenges. The focus on creating a vaccine has forced new ways of thinking. Live, attenuated vaccines are used for measles, rubella or yellow fever. But the risk of infection with HIV raises serious concerns. Inactivated vaccines are safer but weaker and require boosters. These are used for the flu, rabies or hepatitis A and use dead pathogens. But with the rapid mutation rate of HIV, this becomes useless. Other vaccine types are toxoid (tetanus) are subunit (hepatitis B). The most hope for an HIV vaccine will most likely come from DNA or recombinant vector vaccines which are still in experimental stages. These would use parts of the HIV virus to create artificial means of producing antigens that would limit the viruss ability to function or inhibit its ability to adhere to cells at the CD4and CCR5 sites. It may also be able to attach to the viruss

HIV: Research & Nursing Objectives

GP120 causing it to compete with attaching to the cells. (O'Hagan, 2010; (National Institutes of Health, 2003)) An additional challenge for vaccine creation is the fact that we have no animal models for testing. While monkeys can be used for certain types of vaccines, human clinical trials are necessary for DNA or recombinant vaccines.

AIDSInfoNet. (2010). Fact Sheet Number 124: CD4 CELL TESTS. Albuquerque: New Mexico AIDS Education and Training Center at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center. AVERT. (2010, June 30). The Origin of AIDS and HIV and the first cases of AIDS. Retrieved July 9, 2010, from Avert: Averting HIV and AIDS: http://www.avert.org/origin-aidshiv.htm Baltimore, D. (2004). Viruses, viruses, viruses. Engineering and Science , 20-29. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010, June). CDC: Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved July 9, 2010, from cdc.gov: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/factsheets/us_overview.htm Dina Kovarik, M. P. (2009, May 16). HIV Vaccine Research (Powerpoint). Retrieved June 30, 2010, from NWABR.org: http://www.nwabr.org/education/hiv/HIV_KOVARIK_2009.ppt Derek T. O'Hagan, "HIV vaccines", in AccessScience@McGraw-Hill, http://www.accessscience.com.ezlib.gatewaycc.edu:2048, DOI 10.1036/10978542.YB051170 National Institutes of Health. (2003). Understanding Vaccines NIH Publication No. 03-4219. Washington DC: U.S. Depatrment of Health and Human Services.

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5795)

- Perfusion Review - Nclex TipsDocumento37 páginasPerfusion Review - Nclex TipsMichael S. PetryAinda não há avaliações

- Perfusion. Dysrhythmias - Pacemaker.aicdDocumento41 páginasPerfusion. Dysrhythmias - Pacemaker.aicdMichael S. PetryAinda não há avaliações

- Perfusion. Shock - DicDocumento45 páginasPerfusion. Shock - DicMichael S. PetryAinda não há avaliações

- Perfusion. Cad - Acs.miDocumento47 páginasPerfusion. Cad - Acs.miMichael S. PetryAinda não há avaliações

- Psychiatric Health Law and EthicsDocumento38 páginasPsychiatric Health Law and EthicsMichael S. PetryAinda não há avaliações

- Affective Continuum: Depression Suicide BipolarDocumento73 páginasAffective Continuum: Depression Suicide BipolarMichael S. PetryAinda não há avaliações

- Prozac Venlafaxine Duloxetine Amitriptyline BupropionDocumento3 páginasProzac Venlafaxine Duloxetine Amitriptyline BupropionMichael S. PetryAinda não há avaliações

- What Are The Three Major Divisions of The Brain-Forebrain, Midbrain and HindbrainDocumento1 páginaWhat Are The Three Major Divisions of The Brain-Forebrain, Midbrain and HindbrainMichael S. PetryAinda não há avaliações

- Cognition Concept .OCD - Schizophrenia.Delirum - DementiaDocumento64 páginasCognition Concept .OCD - Schizophrenia.Delirum - DementiaMichael S. PetryAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Summary Notes - Topic 6 Microbiology, Immunity and Forensics - Edexcel (IAL) Biology A-LevelDocumento11 páginasSummary Notes - Topic 6 Microbiology, Immunity and Forensics - Edexcel (IAL) Biology A-LevelSaeed AbdulhadiAinda não há avaliações

- Discovery of ViroidsDocumento21 páginasDiscovery of ViroidsKhoo Ying WeiAinda não há avaliações

- Microbiology: Presented by Alyazeed Hussein, BSCDocumento64 páginasMicrobiology: Presented by Alyazeed Hussein, BSCT N100% (1)

- Biological Hazards: Health Hazards Associated With Exposure To Biological AgentsDocumento38 páginasBiological Hazards: Health Hazards Associated With Exposure To Biological AgentsbirisiAinda não há avaliações

- ANTIVIRALEDocumento4 páginasANTIVIRALEVladStefanescuAinda não há avaliações

- Soalan Pelik Part 1Documento6 páginasSoalan Pelik Part 1KatherinaAinda não há avaliações

- Encefalitis 2022Documento10 páginasEncefalitis 2022SMIBA MedicinaAinda não há avaliações

- Hepatitis A: Old and NewDocumento22 páginasHepatitis A: Old and Newahay8181Ainda não há avaliações

- Chapter 1-The Science of Microbiology: Multiple ChoiceDocumento9 páginasChapter 1-The Science of Microbiology: Multiple Choicekirki pAinda não há avaliações

- HTTPS:WWW Ncbi NLM Nih gov:pmc:articles:PMC9867007:pdf:viruses-15-00225Documento17 páginasHTTPS:WWW Ncbi NLM Nih gov:pmc:articles:PMC9867007:pdf:viruses-15-00225Don SarAinda não há avaliações

- Foundations in Microbiology: TalaroDocumento76 páginasFoundations in Microbiology: Talaromertx013Ainda não há avaliações

- Biological Science - Scriptwriting For SiyensikulaDocumento13 páginasBiological Science - Scriptwriting For SiyensikulaJoveth TampilAinda não há avaliações

- TOK Exhibition Sample IBDocumento4 páginasTOK Exhibition Sample IBHARSHA LAinda não há avaliações

- PapayaDocumento6 páginasPapayaSaya SufiaAinda não há avaliações

- MCQS-Ch-5-Variety of Life-Part-Sol-1Documento2 páginasMCQS-Ch-5-Variety of Life-Part-Sol-1All kinds of information on channelAinda não há avaliações

- Ajnfs v4 Id1078Documento5 páginasAjnfs v4 Id1078anita mamoraAinda não há avaliações

- Aseptic MeningitisDocumento4 páginasAseptic MeningitisCheng XinvennAinda não há avaliações

- Bio Term (Ii)Documento262 páginasBio Term (Ii)Kirito AAinda não há avaliações

- Clases 09 Avian EncephalomyelitisDocumento31 páginasClases 09 Avian EncephalomyelitisMijael ChoqueAinda não há avaliações

- Rubella: Dr.T.V.Rao MDDocumento42 páginasRubella: Dr.T.V.Rao MDtummalapalli venkateswara raoAinda não há avaliações

- VACCINESDocumento8 páginasVACCINESzilikajainAinda não há avaliações

- Ritm MonkeypoxDocumento24 páginasRitm MonkeypoxRhodora BenipayoAinda não há avaliações

- MCO Lectures 1-6Documento20 páginasMCO Lectures 1-6sarahebrowningAinda não há avaliações

- 9700 s04 MsDocumento42 páginas9700 s04 MsGhadeer SiamAinda não há avaliações

- Corona - Covid-19Documento8 páginasCorona - Covid-19The Good DoctorAinda não há avaliações

- Drug Repurposing ApproachDocumento30 páginasDrug Repurposing ApproachShofi Dhia AiniAinda não há avaliações

- Ebola Virus Disease: SeminarDocumento13 páginasEbola Virus Disease: Seminarximena rodriguez cadenaAinda não há avaliações

- Principles of Cancer Biology 1st EditionDocumento57 páginasPrinciples of Cancer Biology 1st Editiondarren.barnett949100% (46)

- Antibody Testing For COVID-19: Executive SummaryDocumento23 páginasAntibody Testing For COVID-19: Executive SummaryRafiamAinda não há avaliações

- Types of PathogensDocumento56 páginasTypes of PathogensMelody DacanayAinda não há avaliações