Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Legal Memoranda

Enviado por

Jane Hazel GuiribaDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Legal Memoranda

Enviado por

Jane Hazel GuiribaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Excerpt from Plain Language Legal Writing, 1996 ed, Cheryl Stephens, Law Courts Center-Vanc

Modern formats

Modern conventions for organization and format are best, although there are alternative approaches (many firms have their own styles). The formats suggested here are common. Each format is described and then a comparison is provided below. Following that, there is general discussion of style and format applicable to the two types of documents.

Legal memoranda

Heading and introduction Identify the client and how or why the matter or research assignment was referred to you. Issues Set out the basic legal questions that you will answer. Summary Provide a brief answer to the questions. Brief here means no more than five to ten lines. Statement of facts Set out all the important facts. If there is a dispute over the facts, set out both versions. Be as brief as possible. You can set the facts out chronologically or by another method. (See chapter on organization). One study on judges' opinions of briefs identified inadequate statement of facts as the major problem with legal memoranda. Survey of pertinent statutes While this section is optional, your reader will find it helpful to have the applicable statutory provisions set out. If the provisions are long, paraphrase them here, and set them out on an attachment. Survey of precedents You must review the relevant, primary precedents governing the facts. It is usually not necessary to prepare a history of the case law; the most recent or definitive cases will suffice. Discussion of each issue A dispassionate discussion of the issues and the applicable law is the central purpose of the memorandum. In this section you predict the answers that a court would give if it were faced with your facts, given the pertinent law. Conclusion A summary of your predictions about the state of the law and its application to your case. This is where you expand on the brief answer furnished at the beginning.

Cheryl Stephens, Mentor/Muse 604-739-0443 email@cherylstephens.com

Excerpt from Plain Language Legal Writing, 1996 ed, Cheryl Stephens, Law Courts Center-Vanc

Recommendation You recommend the best solution to the problem facing the client. What should the client do? What do you propose to do for the client? These are the questions you answer here.

Legal opinions

Heading and introduction Identify the client's problem and how the matter came to you. Statement of legal issues raised Pose the question the client needs answered. You may need to rephrase the question that was put to you by the client in way that the law can provide an answer, or you may need to reformulate the question as a result of your analysis of the real issue. Brief answer Give the shortest possible answer to the question posed, or advise the client what must or must not be done. You are entitled to ________, because.... Yes, you may _______. However, you cannot ________.... You cannot ________, but you could consider _______ .... Statement of facts on which the opinion is based Set out the relevant facts. If you and your client are not aware of all the facts, set out the assumptions you have made. Include a warning that the facts and assumptions set out were considered in the state of the law prevailing on the date of the opinion. Discussion of how you reached the conclusion Give your explanation or documentation of the logic and the law, from the client's perspective if possible. Restatement and elaboration of conclusion Provide a fuller explanation of your brief answer at the beginning. If your conclusion is negative, or will disappoint or annoy your client, you may want to lead up to it gradually and save the answer until this point in your letter. It may also help to explain the policy behind the law, which is having the negative effect on your client. Recommendations and proposals for action Suggest what the client should do, or what you will do for the client once you receive instructions. If your conclusion was negative, you can offer alternative courses of action here. If you recommend that the client send a letter to someone to make a demand or a

Cheryl Stephens, Mentor/Muse 604-739-0443 email@cherylstephens.com

Excerpt from Plain Language Legal Writing, 1996 ed, Cheryl Stephens, Law Courts Center-Vanc

proposal, either provide a draft letter, or suggest the relevant wording and request that you see the client's letter before it is sent.

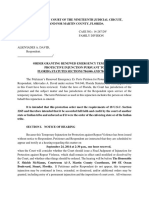

Legal Memorandum

Legal Opinion Overview Heading and Introduction Heading and Introduction Statement of Legal Issues Issues Summary Brief Answer Detail Statement of Facts Statement of Facts Survey of Pertinent Statutes Discussion Review of Precedents Discussion of Each Issue Basis of action Conclusion Detailed Conclusion Recommendation Recommendation

General style matters

Verb Tense Most guidelines suggest that you state: Facts and court decisions in the past tense. Legal rules in the present tense. Recommendations prospectively.

Word Choices In a letter of opinion, you express your considered conclusion based on logic and reason, so the following phrases are seldom appropriate: I believe ... I suppose ... I feel ... I am leaning toward ...

If you don't know something, say so. If you haven't figured something out, say you are still investigating. State clearly that you are speculating on a given set of assumptions, or that you need to further investigate facts before you can form a certain opinion.

Cheryl Stephens, Mentor/Muse 604-739-0443 email@cherylstephens.com

Excerpt from Plain Language Legal Writing, 1996 ed, Cheryl Stephens, Law Courts Center-Vanc

Legalisms Homer E. Moyer Jr. is a former general counsel of the U.S.. Department of Commerce. In his last official act, he issued a memorandum with this caution:

Avoid legalisms. Latin phrases, abbreviations, and other legalisms are the badges of legal writing. However, they are commonly redundant, usually pretentious, and invariably unnecessary. when legalisms punctuate a paragraph, readability suffers. Like lavish capitalization, frequent exclamation marks, and underscoring for emphasis, legalisms serve as crutches when plain English would nicely suffice. The addition of "supra", "arguendo," or "inter alia" rarely amplifies a thought.

Citations A legalism, which does not amplify a thought, has no place in modern writing. There are some legalisms you cannot avoid case citations, for example. But dont cite cases in letters of opinion unless the client is familiar with the case law (for example, accountants with tax cases) or unless the case is groundbreaking. In legal memorandums, don't let citations interfere with your message. Remember to avoid long introductory phrases in your sentences. It is better to let the citation stand alone at the end of a sentence or paragraph. Statements like this make it difficult for the reader to grasp the point, when it finally arrives: In Norton v. Commander, 1999 (89) ALT 34 at 36, 1999 34 WER 684 at 687, the Court held... Instead of following that style, state the important conclusion from the case, and then append the citation. The law is clear that.... See Norton v. Commander, 1999 (89)....

Avoid string citations Cite only the leading case in the text of your letter or memorandum. If you need to cite three or four other cases, put the citations in a footnote. Or use endnotes at the back of your memorandum or as a schedule. No one reads a long string of citations, especially if it is italicized or underlined. The eye just skips over text blocks with such features. String citations also pose a problem to the reader in connecting the introductory words with the ideas, which follow the list of citations.

Get the citation right Use a reference source to ensure that you are using the proper style to cite a case. The Canadian standard is A Uniform Guide to Legal Citations by Carswell. For U.S. case

Cheryl Stephens, Mentor/Muse 604-739-0443 email@cherylstephens.com

Excerpt from Plain Language Legal Writing, 1996 ed, Cheryl Stephens, Law Courts Center-Vanc

citations refer to A Uniform System of Citation produced by the Harvard Law Review Association, or Current American Legal Citations by Bieber and published by Hein.

Statute references Most firms have adopted a particular style for references to statutes. When referring to a current provincial statute, highlight the name and leave out the fuller citation. For example, The Company Act. You may need to quote portions of a statute, regulation, article, transcript, or other material. If you want to quote more of the statute for better context, put it in an appendix. Your reader will appreciate being provided the full text of an item such as a city by-law, which may not be readily available in the law office or business office.

Footnotes Excessive use of footnotes is a common offense among legal writers. Anything, which is essential to understanding the text, should be in the text itself, not in footnotes. In letter opinions, there should be no footnotes. (For authority on this point, see Lost Words: The Economical, Ethical and Professional Effects of Bad Legal Writing, Occasional Papers 7, Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar, American Bar Association, Indianapolis, 1994.)

Quotations Legal writers use too many quotations. Don't quote someone else unless the way the writer has expressed the thought is a gem you cannot equal. When referring to case precedents, summarize or paraphrase whenever you can. When you must quote, be precise in selecting what must be used and what can be cut.

Form and layout

Signposts Other chapters offered general guidelines on how to use titles, headings and other aspects of form and layout. These are specific suggestions for memoranda and opinions. Use keywords in headings and titles to make it easier for those who will be filing or indexing the legal memorandums in your office. A title or headings, which pose the question the memorandum answers, will be helpful to future researchers. Any document longer than three pages needs a table of contents. In short documents, a prose version of the table of contents goes at the very beginning. Extremely long documents may need an index.

Cheryl Stephens, Mentor/Muse 604-739-0443 email@cherylstephens.com

Excerpt from Plain Language Legal Writing, 1996 ed, Cheryl Stephens, Law Courts Center-Vanc

Sample Brief Memorandum Form

Memorandum of Law

To: From: Date:

Harvey Easter Jane Smith January 14, 199Morton v. Hambrook Supreme Court of B.C. Vancouver Registry No. A23456

Concerning:

____________________________________________________________ Our client, JJ Morton, seeks to. This memo is intended to determine whether The legal question to be determined is: What is the obligation of an owner to request that the city make repairs to sidewalks adjacent to his own property? 1. What are the pertinent facts in Morton v. Hambrook? ...(a statement of the facts giving rise to the legal issue) 2. What is the likely conclusion of the Court? ...(a brief statement of your assessment of the state of the law) 3. How is Vancouver City By-Law No. 467A applicable? ...(citation or quotation of applicable statute) 4. What case law has arisen in similar situations? ...(discussion of cases dealing with similar facts or issues) 5. How does the law apply to the facts in this case? ...(your conclusions applying the law to these facts)

Cheryl Stephens, Mentor/Muse 604-739-0443 email@cherylstephens.com

Você também pode gostar

- Divorce in Connecticut: The Legal Process, Your Rights, and What to ExpectNo EverandDivorce in Connecticut: The Legal Process, Your Rights, and What to ExpectAinda não há avaliações

- In the Game: The Highs and Lows of a Trailblazing Trial LawyerNo EverandIn the Game: The Highs and Lows of a Trailblazing Trial LawyerAinda não há avaliações

- 2023 California Peace Officers' Legal and Search and Seizure Field Source GuideNo Everand2023 California Peace Officers' Legal and Search and Seizure Field Source GuideAinda não há avaliações

- A.M. No. 03-04-04-SCDocumento5 páginasA.M. No. 03-04-04-SCGodofredo SabadoAinda não há avaliações

- Electronic Signature A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionNo EverandElectronic Signature A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionAinda não há avaliações

- Void and voidable marriages under Philippine family lawDocumento13 páginasVoid and voidable marriages under Philippine family lawIrma Mari-CastroAinda não há avaliações

- Craig Wright's Notice of ComplianceDocumento2 páginasCraig Wright's Notice of ComplianceForkLogAinda não há avaliações

- Divorce in Wisconsin: The Legal Process, Your Rights, and What to ExpectNo EverandDivorce in Wisconsin: The Legal Process, Your Rights, and What to ExpectAinda não há avaliações

- Agreement To Mediate - BlankDocumento1 páginaAgreement To Mediate - Blankapi-325876920Ainda não há avaliações

- Legal Project Management A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionNo EverandLegal Project Management A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionAinda não há avaliações

- Law Firm Strategies for the 21st Century: Strategies for Success, Second EditionNo EverandLaw Firm Strategies for the 21st Century: Strategies for Success, Second EditionChristoph H VaagtAinda não há avaliações

- Interim Rules of Procedure Governing Intra Corporate ControversyDocumento19 páginasInterim Rules of Procedure Governing Intra Corporate Controversyeast_westAinda não há avaliações

- Deanna Douglas Advance Civil Litigation Lga4000xa Week 6 Assignment 6 1 InterrogatoiesDocumento5 páginasDeanna Douglas Advance Civil Litigation Lga4000xa Week 6 Assignment 6 1 Interrogatoiesapi-302844724100% (1)

- HLURB Case Disputing Nullity of HOA Election and Disqualifying RespondentsDocumento9 páginasHLURB Case Disputing Nullity of HOA Election and Disqualifying RespondentsAndrew OlaguerAinda não há avaliações

- TORTSDocumento14 páginasTORTSakosierikaAinda não há avaliações

- Civil Procedure Digest (Rule 36, Judgment), Arbues 2018Documento10 páginasCivil Procedure Digest (Rule 36, Judgment), Arbues 2018Veronica Chan100% (1)

- Exhibit G51 CHESAPEAKE JUVENILE & DOMESTIC RELATIONS DISTRICT COURT MANUAL Judge Larry D. Willis Sr.Documento3 páginasExhibit G51 CHESAPEAKE JUVENILE & DOMESTIC RELATIONS DISTRICT COURT MANUAL Judge Larry D. Willis Sr.JeffAinda não há avaliações

- General Guardianship Guardianship of MinorsDocumento7 páginasGeneral Guardianship Guardianship of MinorsDelOmisolAinda não há avaliações

- "Practice of Law", Which Shall Be Performed Only by Those Authorized by The HighestDocumento13 páginas"Practice of Law", Which Shall Be Performed Only by Those Authorized by The HighestNoel Alberto OmandapAinda não há avaliações

- DivorceDocumento7 páginasDivorcePhil PandayAinda não há avaliações

- Order Motion For Change of Venue PDFDocumento7 páginasOrder Motion For Change of Venue PDFghostgripAinda não há avaliações

- Pleading Must Be VerifiedDocumento3 páginasPleading Must Be VerifiedAsez Catam-isan AlardeAinda não há avaliações

- John Textor's Restraining Order Against Alki DavidDocumento6 páginasJohn Textor's Restraining Order Against Alki DavidDefiantly.netAinda não há avaliações

- Divorce Steps GuideDocumento2 páginasDivorce Steps GuideMarcAinda não há avaliações

- Guide To Appellate PleadingsDocumento28 páginasGuide To Appellate PleadingsArnold Cavalida BucoyAinda não há avaliações

- EvidenceDocumento362 páginasEvidenceAdi LimAinda não há avaliações

- Complaint Stradley Ronon Stevens & Young, LLP Vs Eb RealtyDocumento32 páginasComplaint Stradley Ronon Stevens & Young, LLP Vs Eb RealtyPhiladelphiaMagazineAinda não há avaliações

- NFL's Proposed Case Management Plan Filing in Brian Flores LawsuitDocumento6 páginasNFL's Proposed Case Management Plan Filing in Brian Flores LawsuitAnthony J. PerezAinda não há avaliações

- Medico Legal GuidelineDocumento10 páginasMedico Legal GuidelineFiraFurqaniAinda não há avaliações

- Guardianship Workshop Script: Parent of The Child Who Seeks A Court Order For Legal Custody of A Minor ChildDocumento3 páginasGuardianship Workshop Script: Parent of The Child Who Seeks A Court Order For Legal Custody of A Minor ChildKkkkkkkkAinda não há avaliações

- 2017 Carolina Gildred V Michael Foster NOTICE of MOTION 15Documento3 páginas2017 Carolina Gildred V Michael Foster NOTICE of MOTION 15Mic FosAinda não há avaliações

- 5C vs. 702 E. FifthDocumento36 páginas5C vs. 702 E. FifththelocaleastvillageAinda não há avaliações

- Auto Accident Request For ProductionDocumento2 páginasAuto Accident Request For ProductionAlan Sackrin, Esq.Ainda não há avaliações

- Order (7-14-2021)Documento30 páginasOrder (7-14-2021)NewsChannel 9 StaffAinda não há avaliações

- Oregon Child CustodyDocumento7 páginasOregon Child CustodyGracie AllenAinda não há avaliações

- 400-2017 Custody Mother AllowedDocumento6 páginas400-2017 Custody Mother AllowedJahirul AlamAinda não há avaliações

- 37 - Motion To SealDocumento122 páginas37 - Motion To SealSarah BursteinAinda não há avaliações

- Facts Which Need To Be ProvedDocumento23 páginasFacts Which Need To Be ProvedSyaz SenoritasAinda não há avaliações

- AdmissionsDocumento3 páginasAdmissionsJfrank Marcom100% (1)

- 2ND DRAFT - Legal ResearchDocumento5 páginas2ND DRAFT - Legal ResearchAnonymous 3SXe3hAinda não há avaliações

- Stia, Et Al vs. Rivera: - Except For Motions Which The Court May Act UponDocumento6 páginasStia, Et Al vs. Rivera: - Except For Motions Which The Court May Act UponDenzhu MarcuAinda não há avaliações

- Letter To Client On Divorce Re: Real Estate Documentsletter To Client On Divorce Re: Real Estate DocumentsDocumento1 páginaLetter To Client On Divorce Re: Real Estate Documentsletter To Client On Divorce Re: Real Estate Documentsjuakin123Ainda não há avaliações

- LLT Forms TocDocumento5 páginasLLT Forms TocRONINM3Ainda não há avaliações

- Memorandum of LawDocumento3 páginasMemorandum of LawSydney AlexanderAinda não há avaliações

- Info Shoppee: Eye Hospital Road SITAPUR 261001 Party DetailsDocumento1 páginaInfo Shoppee: Eye Hospital Road SITAPUR 261001 Party DetailsGaurav JaiswalAinda não há avaliações

- PetitionDocumento3 páginasPetitionJohn Jeric LimAinda não há avaliações

- Response To Motion For Preliminary Injunction PDFDocumento37 páginasResponse To Motion For Preliminary Injunction PDFEditorAinda não há avaliações

- 12:78 Motion To Exclude Evidence Not Contained in TheDocumento4 páginas12:78 Motion To Exclude Evidence Not Contained in ThejusticefornyefrankAinda não há avaliações

- Fortunato, Julienne Wanason, Sandra JD2 Land Titles and Deeds December 8, 2016 Group 13 Quiz AnswersDocumento9 páginasFortunato, Julienne Wanason, Sandra JD2 Land Titles and Deeds December 8, 2016 Group 13 Quiz AnswersjulyenfortunatoAinda não há avaliações

- Affidavit of Income Expenses and Financial DisclosureDocumento13 páginasAffidavit of Income Expenses and Financial DisclosureNathaniel Livingston, Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- PCSO Charity Assistance Services GuideDocumento9 páginasPCSO Charity Assistance Services GuidephenorenAinda não há avaliações

- Cabrera v. Horgas, 10th Cir. (1999)Documento2 páginasCabrera v. Horgas, 10th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Daughter's surname after father's acknowledgmentDocumento3 páginasDaughter's surname after father's acknowledgmentDan BerlonAinda não há avaliações

- Support Pendente Lite DefensesDocumento66 páginasSupport Pendente Lite DefensesGuiller C. MagsumbolAinda não há avaliações

- Statutory Declarations Affidavits Accepted Employment ReferencesDocumento1 páginaStatutory Declarations Affidavits Accepted Employment ReferencesHari BharadwajAinda não há avaliações

- State Motion To Quash SubpoenaDocumento2 páginasState Motion To Quash SubpoenaChad PetriAinda não há avaliações

- Demand Letter To EmployerDocumento2 páginasDemand Letter To EmployerJefferson LegadoAinda não há avaliações

- Rights of Persons Arrested, Detained or Under CIDocumento74 páginasRights of Persons Arrested, Detained or Under CILex Tamen CoercitorAinda não há avaliações

- Bar Cheat Sheet LaborDocumento2 páginasBar Cheat Sheet LaborJane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- Guiriba, JHM: Start MAY 20 END October 15Documento2 páginasGuiriba, JHM: Start MAY 20 END October 15Jane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- Philippine Legal Forms 2015bDocumento394 páginasPhilippine Legal Forms 2015bJoseph Rinoza Plazo100% (14)

- # of CopiesDocumento1 página# of CopiesJane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- Cheat Sheet - Remedial LawDocumento1 páginaCheat Sheet - Remedial LawJane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- Directory Business NumberDocumento4 páginasDirectory Business NumberJane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- Sample of Employment Contact PT EngDocumento3 páginasSample of Employment Contact PT EngjaciemAinda não há avaliações

- BOI - 9G & ACR I-Card Visa Application FormDocumento2 páginasBOI - 9G & ACR I-Card Visa Application FormJane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- Certification of Number of Foreign Employees SampleDocumento1 páginaCertification of Number of Foreign Employees SampleBilly Arupo80% (5)

- BAR TUE SDAY20 17 201 7 20 17: Project Phase Starting Ending Audio Hours DaysDocumento4 páginasBAR TUE SDAY20 17 201 7 20 17: Project Phase Starting Ending Audio Hours DaysJane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- AddressesDocumento1 páginaAddressesJane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- Investigation Data Form - ManilaDocumento2 páginasInvestigation Data Form - ManilaJane Hazel Guiriba100% (1)

- Directory Business NumberDocumento4 páginasDirectory Business NumberJane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- Work For The WeekDocumento6 páginasWork For The WeekJane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- WD Plan 2016 or 2017Documento18 páginasWD Plan 2016 or 2017Jane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- AddressesDocumento1 páginaAddressesJane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment #2Documento2 páginasAssignment #2Jane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- To DoDocumento1 páginaTo DoJane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment #1Documento1 páginaAssignment #1Jane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment #1Documento1 páginaAssignment #1Jane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- Administrative Law: Organization, Functions, and RemediesDocumento1 páginaAdministrative Law: Organization, Functions, and RemediesJane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- IntreDocumento1 páginaIntreJane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- POLITICAL LAW 1-8Documento142 páginasPOLITICAL LAW 1-8schating2Ainda não há avaliações

- IM Clinical Card Case 1 AMDocumento2 páginasIM Clinical Card Case 1 AMJane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- Labor Code of The PhilippinesDocumento25 páginasLabor Code of The PhilippinesTopher Astraquillo60% (5)

- CiviproDocumento188 páginasCiviproIan InandanAinda não há avaliações

- Administrative Law: Organization, Functions, and RemediesDocumento1 páginaAdministrative Law: Organization, Functions, and RemediesJane Hazel GuiribaAinda não há avaliações

- Wills and Succession Memory AidDocumento13 páginasWills and Succession Memory AidmisskangAinda não há avaliações

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocumento15 páginas6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Criminal LawDocumento8 páginasCriminal LawunjustvexationAinda não há avaliações

- Cariaga V Republic G.R. No. 248643Documento19 páginasCariaga V Republic G.R. No. 248643Weddanever CornelAinda não há avaliações

- Entores Ld. v. Miles Far East Corporation. (1955) 2 Q.BDocumento7 páginasEntores Ld. v. Miles Far East Corporation. (1955) 2 Q.Bhadirah azrulAinda não há avaliações

- English 1 2a EdDocumento50 páginasEnglish 1 2a EdAlexandro F. EstremadoyroAinda não há avaliações

- AO No. 7 s'14 Rules and Procedures Governing The Cancellation Ofd REgistered Emancipation Patents (EPS) - ...Documento24 páginasAO No. 7 s'14 Rules and Procedures Governing The Cancellation Ofd REgistered Emancipation Patents (EPS) - ...tagadagat80% (5)

- Failure To Amend The Pleadings Within The Period Specified - Shall Not Be Permitted To Amend Unless The Time Is Extended by The Court. Air 2005 SC 3708Documento38 páginasFailure To Amend The Pleadings Within The Period Specified - Shall Not Be Permitted To Amend Unless The Time Is Extended by The Court. Air 2005 SC 3708Sridhara babu. N - ಶ್ರೀಧರ ಬಾಬು. ಎನ್100% (1)

- Remedial Law Notes on Motion to DismissDocumento17 páginasRemedial Law Notes on Motion to DismissANDY HERNANDEZAinda não há avaliações

- Motion For Substitution of CounselDocumento5 páginasMotion For Substitution of CounselHoreb Felix Villa100% (1)

- Villa, vs. Garcia BosqueDocumento10 páginasVilla, vs. Garcia BosqueXtine CampuPotAinda não há avaliações

- Remedial 1 Syllabus 2019Documento17 páginasRemedial 1 Syllabus 2019Lorenzo HammerAinda não há avaliações

- Future Interest FlowchartDocumento1 páginaFuture Interest FlowchartwittclayAinda não há avaliações

- Reviewer SuccessionDocumento34 páginasReviewer Successionkriselle joy manalo100% (19)

- ProvRem DigestsDocumento190 páginasProvRem DigestsCarlo John C. RuelanAinda não há avaliações

- Transcribed Notes Civil Law Special Lecture Day 2Documento28 páginasTranscribed Notes Civil Law Special Lecture Day 2Michelle BasalAinda não há avaliações

- Affidavit of Dilapitated PlateDocumento1 páginaAffidavit of Dilapitated PlateCybill Astrids Rey RectoAinda não há avaliações

- Didhard Muduni Mparo and 8 Others Vs The GRN of Namibia and 6 OthersDocumento20 páginasDidhard Muduni Mparo and 8 Others Vs The GRN of Namibia and 6 OthersAndré Le RouxAinda não há avaliações

- oRTIGAS V CaDocumento5 páginasoRTIGAS V CaBetson CajayonAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 165851 and G.R. No. 168875 PDFDocumento6 páginasG.R. No. 165851 and G.R. No. 168875 PDFPrincess Hanadi Q. SalianAinda não há avaliações

- SUCS TSN 1st Exam - Long PDFDocumento46 páginasSUCS TSN 1st Exam - Long PDFPrincess Rosshien HortalAinda não há avaliações

- Succession NotesDocumento22 páginasSuccession NotesArki TorniAinda não há avaliações

- AGENCYDocumento59 páginasAGENCYAshburne BuenoAinda não há avaliações

- Last Will RedactedDocumento3 páginasLast Will RedactedRamacho, Tinagan, Lu-Bollos & AssociatesAinda não há avaliações

- 394 - 434 Power of Courts To Open or Vacate Own Judgme-MergedDocumento140 páginas394 - 434 Power of Courts To Open or Vacate Own Judgme-MergedStephane BeladaciAinda não há avaliações

- 5.opulencia vs. CADocumento13 páginas5.opulencia vs. CARozaiineAinda não há avaliações

- Obligations and Contracts Code SummaryDocumento3 páginasObligations and Contracts Code SummaryAnton Ric Delos ReyesAinda não há avaliações

- CPC ProjectDocumento9 páginasCPC Projectsalman panwarAinda não há avaliações

- Article 13 (2) Indian ConstitutionDocumento15 páginasArticle 13 (2) Indian ConstitutionAmogh BansalAinda não há avaliações

- 97-Co Vs Civil RegistrarDocumento13 páginas97-Co Vs Civil RegistrarChristie CastillonesAinda não há avaliações

- Transfer of Property Act Notes Transfer of Property Act NotesDocumento18 páginasTransfer of Property Act Notes Transfer of Property Act NotesHemant TiwariAinda não há avaliações

- Final Documents 1Documento4 páginasFinal Documents 1Anonymous 4m3aTSsfnHAinda não há avaliações

- Surety Bonds in Plain EnglishDocumento11 páginasSurety Bonds in Plain English: MacAinda não há avaliações