Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

A Qualitative Study of The Perceptions of Coronary Heart Disease Among

Enviado por

Stan LamDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

A Qualitative Study of The Perceptions of Coronary Heart Disease Among

Enviado por

Stan LamDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

PATIENT EDUCATION AND INFORMATION NEEDS

A qualitative study of the perceptions of coronary heart disease among Hong Kong Chinese people

Choi Wan Chan, Violeta Lopez and Joanne WY Chung

Aims and objectives. The aim of this study was to investigate the perceptions of coronary heart disease among a sample of Hong Kong Chinese people. Background. Coronary heart disease is increasing among Chinese populations. Reducing coronary heart disease risk is highly dependant on a persons evaluation of the risks and lifestyle behaviour. However, Chinese perceptions of coronary heart disease and the risks have been underexplored. Design. A qualitative study was conducted using focus group interviews. Method. Focus group interviews were tape recorded and transcribed. The data were analysed using content analysis. Results. The results show that the Hong Kong Chinese participants underestimated the severity of coronary heart disease. Perceptions of risk of coronary heart disease were inuenced by the risk factors, symptoms, age, optimism, levels of suffering from coronary heart disease and reliance on medical professionals. Most of the participants perceived that this is because of inadequate understanding of coronary heart disease and lack of resources for coronary heart disease health education. Conclusion. Societal readiness is paramount in imparting accurate coronary heart disease knowledge to mediate the perception of coronary heart disease as a major health problem that affects the Chinese population. Relevance to clinical practice. Understanding the Chinese participants perceptions of coronary heart disease is vital in developing illness prevention and health promotion strategies to increase their levels of knowledge of coronary heart disease risk factors reduction. Key words: coronary heart disease, focus groups, Hong Kong Chinese, nurses, qualitative, risk

Accepted for publication: 18 January 2010

Introduction

Heart disease as coded by the World Health Organizations International Classication of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD9) is the second major cause of death in Hong Kong. More than 68% of all deaths from heart disease results from coronary heart disease (CHD) (Hospital Authority 2006). Deaths from CHD have increased over the years between 19812005, rising from 2103 deaths in 19813719 deaths in

Authors: Choi Wan Chan, PhD, MNS, RN, Research Associate, Research Centre for Nursing and Midwifery Practice, Australian National University; Violeta Lopez, PhD, RN, FRCNA, Professor and Director, Research Centre for Nursing and Midwifery, School of Medicine, Australian National University, ACT, Australia; Joanne WY Chung, PhD, RN Chair Professor and Head, Department of Health and Physical Education, The Hong Kong Institute of Education, Hong Kong, China

2003 and 4003 deaths in 2005 (Hospital Authority 2004, 2006). According to Lam et al. (2002, 2004), the causes of CHD-related deaths in Hong Kong were because of the economic development and concomitant westernisation. This is further supported by Ko et al. (2007) who reported that the increase mortality of CHD in Hong Kong was because of the peoples increasing adoption of unhealthy lifestyle habits, smoking, physical inactivity and unhealthy dietary habits. Beaglehole (2001) projected that CHD will remain one of the

Correspondence: Choi Wan Chan, Research Associate, Research Centre for Nursing and Midwifery Practice, Australian National University, The Canberra Hospital, Building 6, Level 3, East Wing, Yamba Drive, Garran, ACT 2605, Australia. Telephone: (614) 2412 5223. E-mail: cwanchan@netvigator.com

2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 11511159 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03526.x

1151

CW Chan et al.

leading causes of death in 2020. As such, if preventive medicine is to make a difference to human well-being, then CHD in Chinese populations must be urgently addressed. Changes in health and lifestyle play an important role in reducing CHD mortality and morbidity (Stampfer et al. 2000, Knoops et al. 2004, Yusuf et al. 2004). The perception of disease inuences the way people process their health risks and as such is fundamental in bringing about personal judgments that guide health changes (Weinstein 1988, Weinstein & Sandman 1992, Bandura 1997, Glanz et al. 2002, Pender et al. 2002). Research has shown that the perception of CHD has an important effect on personal risk formulation (Hunt et al. 2000, DeSalvo et al. 2005), the prediction of preventive behaviour (Ali 2002) and changes towards a healthy lifestyle (Hampson et al. 2000, Weinman et al. 2000, Gump et al. 2001). However, little is known about perceptions of CHD among Chinese populations, which constitute about one-fth of the worlds population (Daily Almanac 2007a,b) and among which the mortality and morbidity of CHD are increasing (Beaglehole 2001). It has been highlighted that health promotion and interventions are more effective when they are based on a clear understanding of the cultural and ethnic perspectives that inform health perceptions and behaviour (Hunt et al. 2000). Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore perceptions of CHD in a sample of Hong Kong Chinese people.

Methods

Sampling method and sample

Convenience and snowball sampling methods were used. To obtain a broad range of views and opinions, the sample contained three target populations: a low-risk public (LRP) group, a multiple risk factors (MRF) group and a myocardial infarction (MI) group. The three target populations were grouped according to the eight CHD risk factors identied by Shepherd et al. (1997) including: personal history of CHD, high blood pressure, or diabetes; family history of CHD; smoking history; excessive alcohol consumption; high cholesterol level; exercise 30 minutes/day less than once a month; self-report of poor eating habit and attitude; and poor attitude about healthy lifestyle. The LRP participants who had three or less CHD risk factors were recruited from the public domains (e.g. community centres, churches, university compounds). The MRF participants had four or more CHD risk factors with or without a history of CHD, and the MI participants had a medical diagnosis of MI. Participants in the MRF and MI groups were recruited from one cardiac rehabilitation and prevention centre in the community-based

1152

hospital. All of the participants were aged 18 or over. These target populations were grouped prior to the focus group interviews. Furthermore, in view of possible regional differences in views and opinions of the study topic, the participants were recruited from three geographical areas including Hong Kong Island, Kowloon and New Territories to maximise the generalisability of ndings among the Hong Kong population. Same sex focus group interviews were conducted to facilitate open discussions to occur as participants felt at ease during the conversation instead of in a position of being passive and/or dominant, if they are in a group with mixed genders (Grbich 1999). This also addresses some cultural norms and issues in the Hong Kong Chinese society as the male being more dominant than women (Cheung 1997) and that the Hong Kong Chinese women have been reported to have higher level of self-esteem and better adjustments in the consequences of their diseases than men (Ng et al. 2003). The study sample consisted of different target populations, both genders and a broad age range. Morgan (1997) suggests that the difference in attributes of the participants both within and across groups is important in the determination of the number of focus groups. One focus group may not reect either the unusual composition of that group or the dynamics of that unique set of participants, while more than one focus group could provide a safe ground to conclude the data and to reect usual and unusual data (Carey 1995, Morgan 1997). Therefore, 12 focus groups were initially planned until data saturation is achieved. After data saturation had been achieved, the sample consisted of 18 single-gender focus groups (nine male and nine female groups). Data saturation was the stage at which no new information emerged from the focus group interview data, and the researcher obtained repeated data from the focus group participants (Polit & Hungler 1995).

Data collection and focus group interviews

After gaining approval from the university and hospital ethics committees, the researcher recruited the participants by approaching the community, cardiac rehabilitation and prevention centres, churches and universities student common room. The recruitment of participants was also facilitated by the person in-charge of the centres. For snowball method of recruitment, those eligible participants who consented to participate in the study were requested to ask other people in their universities, neighbourhood or community centres to contact the researcher if they were willing to participate in the study. Each eligible participant recruited was given detailed explanation of the nature and

2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 11511159

Patient education and information needs

Qualitative study of the perceptions of CHD

purpose of the study. They were also informed that participation was on a voluntary basis and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. They were assured their condentiality and privacy would be maintained. They were also given time to ask questions regarding the study. Those who agreed to participate were asked to sign the consent form. Demographics and health history data including information of CHD risk factors were collected, so that grouping could be determined according to their levels of CHD risk prior to focus group interviews. The focus group interviews were mostly conducted in the community centres and the cardiac rehabilitation and prevention centres. Focus group interviews were conducted during an eight-month period from November 2003June 2004. Each interview lasted between 6090 minutes. An interview schedule was used to focus the discussion on the perceptions of CHD. The interview started with questions such as Could you tell me what you understand about coronary heart disease? and Do you think CHD poses a threat to your health? Follow-up questions were then raised to explore the initial answers of the participants further. The rst author served as a neutral and non-directive moderator who guided the interviews, raised the follow-up questions and managed the group dynamics by encouraging quiet participants to share their views, ensuring that outspoken participants did not bias the discussion and encouraging respondents to elaborate on views that differed from the predominant opinion. All interviews were conducted by the rst author in Chinese and were audiotaped with the permission of the participants. Prior to data analysis, the rst author listened carefully to each tape several times to obtain a sense of the meaning of that data. Then, the audiotaped interviews were transcribed verbatim into Chinese and then translated into English.

The two independent researchers discussed the analysed data to ensure that they were reliably interpreted and that the data gave a valid representation of the phenomena under study (Berg 2007). The audiotaped interviews and verbatim quotes from the participants were also used as evidence to conrm the trustworthiness of the qualitative data.

Results

Demographic data

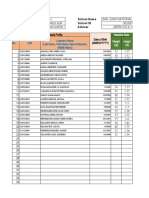

The total sample consisted of 100 participants (LRP = 57, MRF = 27, MI = 21). The sample consisted of 52% men and 48% women, age range was 1888 years old (M = 565; SD 201). There were 10 LRP and four in each of the MRF and MI focus groups. Details of the demographic background of the focus group participants are summarised in Table 1.

Qualitative ndings

Based on the descriptions of the participants perceptions of CHD, the data were divided into three categories: (1) perceived seriousness of CHD, (2) perceived risk of CHD and (3) perceived opportunities to understand CHD. Perceived seriousness of CHD Many of the LRP, MRF and MI participants underestimated the seriousness of CHD, as they believed it to be an invisible disease with minimal suffering. In terms of the perceptions of the participants regarding the impact of CHD in a societal context, a distinct lack of the awareness of CHD was demonstrated because stroke, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), hypertension and diabetes were all perceived as being more signicant diseases. For example, SARS, as an infectious and incurable disease, was perceived to be more urgent and much more serious, which inuenced the perceptions of the participants that led them to underestimate the seriousness of CHD as one LRP male participant said:

I think the impact of CHD when compared with SARS is that the two are different. To me, the degree of danger of CHD is small. (LRP, group 3, male)

Data analysis

The focus group data were analysed using content analysis. Content analysis is a dynamic form of analysis that assigns verbal data categories and subcategories through the coding of words, phrases and themes from the interview scripts (Sandelowski 2000, Berg 2007). Data were subjected to both manifest and latent content analysis, where the manifest level of analysis was the coding of directly observable descriptions and the latent level of analysis was the coding of signicant underlying meanings (Boyaatzis 1998, Berg 2007). Two researchers analysed the qualitative data independently. The codes and categories that were generated from the data were continually revised and systematically applied in an ongoing analytical process.

Being rendered immobile and physically dependent on others as a result of stroke was perceived to engender greater suffering than death. A MRF male participant who had a history of both minor stroke and CHD gave a typical response in underestimating the severity of CHD, which he saw as being less important than stroke as pointed out:

1153

2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 11511159

CW Chan et al. Table 1 Demographic background of the focus group participants

Low-risk public 10 Focus groups (n = 57) Gender n (%) Male Female Mean age SD (range) Education: n (%) No formal education Primary Secondary Postsecondary Degree or above Employment status: n (%) Currently working Retired Homemaker Student

Multiple risk factor group 4 Focus groups (n = 22)

Myocardial infarction group 4 Focus groups (n = 21)

28 (49) 29 (51) 496 235 (1888) 9 12 18 4 14 16 23 10 8 (158) (211) (316) (70) (246) (281) (404) (175) (140)

11 (50) 11 (50) 645 83 (4477) 5 8 6 0 3 2 15 5 0 (227) (364) (273) (00) (136) (91) (682) (227) (00)

13 (62) 8 (38) 667 84 (4578) 4 10 4 3 0 3 14 4 0 (190) (476) (190) (143) (00) (143) (667) (190) (00)

I am afraid of the recurrence of stroke. I am really afraid of it, as I do not know why I had a stroke. I saw stroke patients with paralysis in the arms and legs who couldnt walk well. If I had it, then I would suffer a lotCoronary heart disease is already there [laughed]. I am really afraid of [stroke]. (MRF, group 3, male)

was a child. I have thought that I would get it one day. And I smoked a lot previously. (MRF, group 3, male)

Another LRP female participant said:

Because I am overweight and do not exercise, I know I am at risk. I worry that I will have that problem [heart disease]. (LRP, group 1, female)

The suffering that results from hypertension and diabetes was also commonly emphasised by participants with an overwhelming perception that hypertension would lead to stroke, which would eventually cause suffering. Participants with diabetes also emphasised the serious complications arising from the disease and were preoccupied by the Chinese cultural belief that eating is a kind of fortune and joy and their suffering is a result of dietary restrictions. When this result was compared with other groups for similarities and differences, their underestimation of the severity of CHD were similar. Perceived risk of CHD CHD risk factors such as eating habits, regular exercise, family history of CHD, obesity, stress, menopause, diabetes and high blood cholesterol were all reported in the risk formulations of the participants. Participants who believed that they were not subject to CHD risk factors perceived themselves to be at a low risk of developing CHD. Both male and female participants, in the LRP, MRF and MI groups, who were able to identify their own risk factors of developing the disease reported fear about the perceived risk of CHD, as demonstrated by verbatim quotes such as:

I think I have many risk factors that include work pressure, diet and no xed time for rest. I have them all. I have been a fat boy since I

The presence of CHD symptoms was used by some participants to evaluate their risk of CHD. According to their descriptions, participants who had experienced CHD symptoms perceived themselves to be at risk of CHD, whereas those who believed that they did not have any symptoms of CHD did not see themselves as being at risk of developing the disease. This condition was exemplied by the words of one MRF male participant, who recalled that he had underestimated his own risk in the past. He had ignored his doctors suggestion to undergo a cardiac investigation because he did not have any chest pain and other bodily symptoms when he said:

I did not do it [cardiac catheterisation] as I didnt think that I had a problem. I thought that it was psychological problem. I did not have pain here [pointing to the chest]. I did not have any problems anywhere in the body. (MRF, group 3, male)

Age was another factor used by participants in calculating their risk of CHD. Many of the participants who perceived themselves to be too young to have CHD reported a low risk of CHD. However, few of the older participants had a different opinion of their own risk. They had a low perception of their risk of CHD and cited that they had

1154

2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 11511159

Patient education and information needs

Qualitative study of the perceptions of CHD

earned enough of life as the reason for this as one MRF female participant recounted:

There is no need to be afraid. I am now 70 years old What need is there to be afraid of? I have earned [my life] already. (MRF, group 4, female)

Being optimistic about the risk of CHD was identied as a factor that led both male and female participants to negate their own personal risk of CHD. This is typied by the statement of a male MI participant who believed his optimistic character negated his future risk of CHD, despite the fact that he had a history of MI, was older and was still a current smoker. The level of suffering caused by CHD emerged as a factor mediating the perception of the risk of CHD. Several participants believed that CHD as a disease causes little suffering, which made them less likely to view CHD as a threatening disease and hence undermined their perception of the risk of CHD. Some of the participants stated that they were highly dependent on their doctors to look after their health, which they felt reduced the risk and threat posed by CHD. An MI participant who had depended on doctors to look after his health in the past stated that he had overlooked the role of diabetes and hypertension in increasing his risk of developing CHD until he suffered a cardiac event. An analysis of the data on risk factors and symptoms across the three populations revealed the LRP participants to be more likely to describe themselves as being at a low risk of CHD, as they believed they did not have any risk factors and had not experienced any CHD symptoms. In contrast, the MRF and MI participants were more likely to describe themselves as being at a high risk of CHD or of the recurrence of CHD, as they were able to identify the risk factors that applied to them and had experienced CHD symptoms. In terms of age as a factor in risk perception, the majority of the LRP participants perceived themselves as to be less at risk of CHD because of their young age. However, because of their perception of having earned enough of life, the two groups of LRP participants and three groups of MRF and MI participants who were older had a similarly low perception of their risk of CHD. Optimism, perceptions of the level of suffering arising from CHD and reliance on medical professionals were also factors that affected the perception of risk among the participants, with the LRP participants being more likely to adopt these factors to negate their personal risk of CHD than participants in the MRF and MI groups. The descriptions of the participants clearly demonstrated the inuences of CHD risk factors, CHD symptoms, age, opti-

mism, the level of suffering caused by CHD and reliance on medical professionals in the estimation of their personal risk and of the threat posed by CHD. Of these issues, risk factors, symptoms and age were frequently used by most of the LRP, MRF and MI participants in evaluating risk, although the various groups of participants had a different perception of the contribution of these factors to the risk of CHD. Perceived opportunities to understand CHD Many of the participants felt that they lacked access to information about CHD, which was consistently reported by different age groups and across all of the target populations. This was typied by one of the verbatim quote where a young male participant in one of the LRP groups reported that it was difcult to locate CHD information:

Those pamphlets are not so detailed and are quite simple. They are only 12 pages and cover only some of the issues and preventive methods. On the Internet, ah sometimes ah you cannot be sure [whether] it is right or not and it may be not up to date. So, I feel it is difcult to nd a means of knowing exactly what CHD is. (LRP, group 2, male)

The participants also expressed that CHD is a disease that is difcult to understand. For example, a male MI participant who had undergone a cardiac rehabilitation programme emphasised that as a lay person, he had found the disease difcult to understand as stated:

Put simply, for the general public and from a laymans perspective, it means that my heart has a problem. I did think that. But I didnt think that it was heart disease, because my knowledge of heart disease was inadequate. Heart disease comes in many forms, such as CHD, myocardial infarction, heart failure. Now I know about them, as I have read about them. At that time though, I had no idea what they were and what the symptoms were. (MI, group 1, male)

Other participants reported that although they had seen posters and banners about CHD, they did not really benet from it because of misconception and misunderstanding related to CHD as reported in category 1 - perceived seriousness of CHD. They believed that CHD causes little suffering compared with other diseases.

Discussion

To date, there has been little information about Hong Kong Chinese perceptions of CHD. In this study, three main categories of perceptual information about CHD have been identied, namely, perceived seriousness of CHD, perceived risk of CHD and perceived opportunities for better understanding CHD. This contributes to improve our understanding

1155

2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 11511159

CW Chan et al.

of how CHD is perceived by Hong Kong Chinese people. However, it must be noted that the current ndings were obtained from a single Hong Kong Chinese sample compiled using the convenience and snowball sampling methods, and these limitations should be acknowledged in generalising the results to other populations. The Hong Kong Chinese participants in this study heavily emphasised the concepts of physical independence and mobility, suffering and the dichotomy of curable vs. incurable disease in relation to the perceived severity of CHD. Stroke, hypertension, diabetes and SARS were all regarded as more serious health problems than CHD, which is consistent with ndings from previous studies where CHD was repeatedly under-reported as a major health concern (Gabhainn et al. 1999, Mosca et al. 2000, Vanhecke et al. 2006). In addition, the participants in this study likened CHD to a sudden event with minimal suffering that leads to a peaceful and silent death, a romantic idea about CHD that may also account for the similar underestimation of CHD severity by all risk groups. This indicates that public awareness about CHD must be increased and accurate messages about CHD imparted through public education without delay. Risk factors, symptoms, age, optimism, level of suffering from the disease and reliance on medical professionals were all considered by the participants in evaluating their risk of CHD. It is possible that the phenomenon of optimistic bias may explain the perceptions of the participants who reported themselves as being at a low risk of CHD. Optimistic bias or unrealistic optimism refers to people who tend to underestimate their own risk of disease and is a phenomenon that has been widely reported in the literature (Avis et al. 1989, Marteau et al. 1995, Van Tiel et al. 1998, Green et al. 2003, Moran et al. 2003, Vanhecke et al. 2006). The perceived CHD risk attributed to the various risk factors among the present sample of participants was quite consistent with the results of a previous study (Perkins-Porras et al. 2006), in that a high percentage (72%) of participants with a positive family history of CHD attributed heart disease to heredity, a high percentage (85%) of obese participants attributed CHD to being overweight and almost half (49%) of the sedentary participants attributed it to a lack of exercise. Reliance on medical professionals as a factor in determining the evaluation of the risk of CHD among the participants may be because of the cohort effect, in that the sample of participants who were older had greater faith in medical judgments of illness and were of a generation that tends to view doctors as a source of authority. However, defence mechanism may also be a factor, in that by depending on a doctor to look after their health, they in effect freed themselves from being preoccupied with any risk or threat

1156

of disease and thus placed themselves outside of the parameters of increased risk of CHD. The nding that CHD is difcult to comprehend is consistent with previous studies, where both layman and patients with CHD reported having difculty in articulating the processes that contribute to CHD, which consequently resulted in misconceptions about the disease (Wiles & Kinmonth 2001, Karner et al. 2003, Angus et al. 2005). The lack of accessible information about CHD knowledge and how to prevent CHD found in this study concur with the result of the study of Farooqi et al. (2000) in the South Asians living in the UK and the result of Steenkiste et al. (2004) among the Dutch people. In both of these studies, the participants reported that information about the prevention of cardiac disease was insufcient. There are plausible explanations for our ndings. First, the understanding of CHD among lay people and patients and their need for information about CHD have been underexplored. This would lead to incongruence between the CHD information and health messages that are delivered by healthcare professionals and the information that is expected by lay people and patients. This is a phenomenon that has been consistently highlighted in the literature (Wiles & Kinmonth 2001, Angus et al. 2005, Allmark & Tod 2006) and indicates a pressing need for health professionals to explore the understanding of CHD among lay people and patients and their informational needs and to provide information that can be easily understood, interpreted and used. The second possible explanation is that there are few effective public health education programmes and campaigns devoted to CHD as a result of increased attention being paid to other recent health problems in Hong Kong, such as SARS and avian inuenza. This may have contributed to a decrease in awareness of CHD among the public and the disengagement of the public from a socially facilitating environment where they can acquire opportunities to secure better knowledge and information about CHD. To prevent CHD, it is important to promote a facilitating environment where people can share common social concerns, discuss issues such as health, illness and healthy behaviour in relation to CHD and gain informational support to promote CHD health and prevent the disease. Adequate and effective public campaigns are urgently needed to create an environment where people can understand and increase their awareness of CHD and its prevention.

Conclusion

The present qualitative study adds knowledge to the literature by demonstrating that the severity of CHD is

2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 11511159

Patient education and information needs

Qualitative study of the perceptions of CHD

underestimated by the Hong Kong Chinese population, that the population has an unrealistic optimism about the disease and that there is an inadequate understanding of CHD, all of which have created a lack of societal readiness to engage in coronary health promotion and disease prevention. Thus, the study highlighted that societal readiness to impart accurate CHD information among Chinese populations is vital in coronary healthcare for containing CHD, achieving wellbeing and decreasing the health costs of heart disease, especially as Chinese people constitute such a large portion of the worlds population. This study reports ndings on the perceptions of CHD from a single sample and used the convenience and snowball sampling methods to recruit participants, which limits the generalisability of the results. More research among Chinese populations is therefore suggested, as this is a largely underexplored area.

health promotion strategies to increase their levels of knowledge of CHD risk factors reduction.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge with gratitude the men and women who participated in this study. Their willingness to be interviewed provided us with useful information. Special thanks to Dr Fielding, Prof Thompson, Dr Yu and Prof Twinn for their preliminary advice. We are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments of this manuscript.

Contributions

Study design: CWC; data collection: CWC; data analysis: CWC, VL, JC and manuscript preparation: CWC, VL, JC.

Relevance to clinical practice

Understanding the Hong Kong Chinese participants perceptions of CHD is vital in developing illness prevention and

Conict of interest

There are no conicts of interest.

References

Ali NS (2002) Prediction of coronary heart disease prevention behaviors in women: a test of the health belief model. Women and Health 35, 8396. Allmark P & Tod A (2006) How should public health professionals engage with lay epidemiology? Journal of Medical Ethics 32, 460463. Angus J, Evans S, Lapum J, Rukholm E, Onge RS, Nolan R & Michel I (2005) Sneaky disease: the body and health knowledge for people at risk for coronary heart disease in Ontario, Canada. Social Science and Medicine 60, 21172127. Avis NE, Smith KW & Mckinlay JB (1989) Accuracy of perceptions of heart attack risk: what influences perceptions and can they be changed? American Journal of Public Health 79, 16081612. Bandura A (1997) Self-efcacy: The Exercise of Control. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York. Beaglehole R (2001) Global cardiovascular disease prevention: time to get serious. Lancet 358, 661663. Berg BL (2007) Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. Pearson, New York. Boyaatzis RE (1998) Transforming Qualitative Information: The Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks. Carey MA (1995) Comment: concerns in the analysis of focus group data. Qualitative Health Research 5, 487495. Cheung FM (1997) Gender role development. In Growing up the Chinese Way (Lau S ed.). The Chinese University Press, Hong Kong, pp. 4568. Daily Almanac (2007a) China: History, Geography, Government and Culture. Available at: http://www.infoplease. com/ipa/A0107411.html (accessed 15 December 2007). Daily Almanac (2007b) Total Population of the World by Decades, 19502050. Available at: http://www.infoplease. com/ipa/A0762181.html (accessed 15 December 2007). DeSalvo KB, Gregg J, Kleinpeter M, Pedersen BR, Stepter A & Peabody J (2005) Cardiac risk underestimation in urban, Black women. Journal of General Internal Medicine 20, 11271131. Farooqi A, Nagra D, Edgar T & Khunti K (2000) Attitudes to lifestyle risk factors for coronary heart disease amongst South Asians in Leicester: a focus group study. Family Practice 17, 293297. Gabhainn SN, Kelleher CC, Naughton FC, Flanagan M & McGrath MJ (1999) Socio-demographic variations in perspective on cardiovascular disease and associated risk factors. Health Education Research 14, 619628. Glanz K, Rimer BK & Lewis FM (2002) Health Behavior and Health Education Theory, Research and Practice. JosseyBass A Wiley Imprint, San Francisco. Grbich C (1999) Qualitative Research in Health. Sage Publications, London. Green JS, Grant M, Hill KL, Bizzolara J & Belmont B (2003) Heart disease risk perception in college men and women. Journal of American College Health 51, 207211. Gump BB, Matthews KA, Scheier MF, Schulz R, Bridges MW & Magovern GJ (2001) Illness representations according to age and effects on health behaviors following Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 49, 284289. Hampson SE, Andrews JA & Barckley M (2000) Conscientiousness, perceived risk and risk-reduction behaviors: a

2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 11511159

1157

CW Chan et al. preliminary study. Health Psychology 19, 496500. Hospital Authority (2004) Hospital Authority Statistical Report. Hospital Authority, Hong Kong. Hospital Authority (2006) Hospital Authority Statistical Report. Hospital Authority, Hong Kong. Hunt K, Davison C, Emslie C & Ford G (2000) Are perceptions of a family history of heart disease related to healthrelated attitudes and behaviour? Health Education Research 15, 131143. Karner A, Goransson A & Bergdah B (2003) Patients conceptions of coronary heart disease a phenomengraphic analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 17, 4350. Knoops KTB, De Groot LCPGM, Kromhout D, Perrin A, Moreiras-Varela O, Menotti A & Van Staveren WA (2004) Mediterranean diet, lifestyle factors and 10-year mortality in elderly European men and women. Journal of American Medical Association 292, 14331439. Ko GTC, Chan JCN, Tong SDY, Chan AWY, Wong PTS, Hui SSC, Kwok R & Chan CLW (2007) Associations between dietary habits and risk factors for cardiovascular diseases in a Hong Kong Chinese working population the Better Health for Better Hong Kong (BHBHK) health promotion campaign. Asia Pacic Journal of Clinical Nutrition 16, 757765. Lam TH, Chung SF, Janus ED, Lau CP, Hedley AJ, Chan HW, Chow L, Keung KK & Li SK (2002) Smoking, alcohol drinking and non-fatal coronary heart disease in Hong Kong Chinese. Annals of Epidemiology 12, 560567. Lam TH, Ho SY, Hedley AJ, Mak KH & Leung GM (2004) Leisure time physical activity and mortality in Hong Kong: casecontrol study of all adult deaths in 1998. Annals of Epidemiology 14, 391 398. Marteau TM, Kinmonth A, Pyke S & Thompson SG (1995) Readiness for lifestyle advice: self-assessments of coronary risk prior to screening in the British family heart study. British Journal of General Practice 45, 58. Moran S, Glazier G & Armstrong K (2003) Women smokers perceptions of smoking-related health risks. Journal of Womens Health 12, 363372. Morgan DL (1997) Focus Groups as Qualitative Research. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks. Mosca L, Jones WK, King KB, Ouyang PR, Redberg RF & Hill MN (2000) Awareness, perception and knowledge of heart disease risk and prevention among women in the United States. Archives of Family Medicine 9, 506 551. Ng JYY, Tam SF, Man DWK, Cheng LC & Chiu SW (2003) Gender differences in self-esteem of Hong Kong Chinese with cardiac diseases. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 26, 6770. Pender NJ, Murdaugh CL & Parsons MA (2002) Health Promotion in Nursing Practice. Prentice Hall, New Jersey. Perkins-Porras L, Whitehead DL & Steptoe A (2006) Patients beliefs about the causes of heart disease: relationships with risk factors, sex and socio-economic status. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation 13, 724730. Polit DF & Hungler BP (1995) Nursing Research: Principles and Methods. J.B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia. Sandelowski M (2000) What happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health 23, 334340. Shepherd J, Alcade V, Befort P-A, Boucher B, Erdmann E, Gutzwiller F, van Hemert TJ, Jordan-Ghizzo I, Menotti A, Schioldborg P, Thompson DR, Turner M & Umlauf B (1997) International comparison of awareness and attitudes towards coronary risk factor reduction: the HELP study. Journal of Cardiovascular risk 4, 373384. Stampfer MJ, Hu FB, Manson JE, Rimm EB & Willett WC (2000) Primary prevention of coronary heart disease in women through diet and lifestyle. The New England Journal Medicine 343, 1723. Steenkiste BV, Weijden TVD, Timmermans D, Vaes J, Stoffers J & Grol R (2004) Patients ideas, fears and expectations of their coronary risk: barriers for primary prevention. Patient Education and Counseling 55, 301307. Van Tiel D, Van Vliet KP & Moerman CJ (1998) Sex differences in illness beliefs and illness behaviour in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Patient Education and Counseling 33, 143147. Vanhecke TE, Miller WM, Franklin BA, Weber JE & McCullough PA (2006) Awareness, knowledge and perception of heart disease among adolescents. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation 13, 718 723. Weinman J, Petrie KJ, Sharpe N & Walker S (2000) Causal attributions in patients and spouses following first-time myocardial infarction and subsequent lifestyle changes. British Journal of Health Psychology 5, 263273. Weinstein ND (1988) The precaution adoption process. Health Psychology 7, 355386. Weinstein ND & Sandman PM (1992) A model of the Precaution Adoption Process: evidence form home radon testing. Health Psychology 11, 170180. Wiles R & Kinmonth A (2001) Patients understandings of heart attack: implications for prevention of recurrence. Patient Education and Counseling 44, 161169. Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpun S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, McQueen M, Budaj A, Pais P, Varigos J & Liu L on behalf of the INTERHEART Study Investigators (2004) Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART STUDY): casecontrol study. Lancet 364, 937952.

1158

2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 11511159

Patient education and information needs

Qualitative study of the perceptions of CHD

The Journal of Clinical Nursing (JCN) is an international, peer reviewed journal that aims to promote a high standard of clinically related scholarship which supports the practice and discipline of nursing. For further information and full author guidelines, please visit JCN on the Wiley Online Library website: http:// wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/jocn

Reasons to submit your paper to JCN:

High-impact forum: one of the worlds most cited nursing journals and with an impact factor of 1194 ranked 16 of 70 within Thomson Reuters Journal Citation Report (Social Science Nursing) in 2009. One of the most read nursing journals in the world: over 1 million articles downloaded online per year and accessible in over 7000 libraries worldwide (including over 4000 in developing countries with free or low cost access). Fast and easy online submission: online submission at http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/jcnur. Early View: rapid online publication (with doi for referencing) for accepted articles in nal form, and fully citable. Positive publishing experience: rapid double-blind peer review with constructive feedback. Online Open: the option to make your article freely and openly accessible to non-subscribers upon publication in Wiley Online Library, as well as the option to deposit the article in your preferred archive.

2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 11511159

1159

Você também pode gostar

- Ecklonia Cava Extract, Healthy Habits Super Antioxidant - Whole Food Health ProductsDocumento10 páginasEcklonia Cava Extract, Healthy Habits Super Antioxidant - Whole Food Health ProductslisinfotauAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Diet Solution Metabolic Typing TestDocumento10 páginasThe Diet Solution Metabolic Typing TestkarnizsdjuroAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Muet EssaysDocumento29 páginasMuet EssaysBabasChongAinda não há avaliações

- Top 10 Interesting Fun Facts About BasketballDocumento21 páginasTop 10 Interesting Fun Facts About Basketballpaolo furio100% (1)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Antepartum CareDocumento20 páginasAntepartum Careapril jholynna garroAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 1 5 Super FinalOther ResearchDocumento176 páginasChapter 1 5 Super FinalOther ResearchjeffreyAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Physical Education: DepedDocumento54 páginasPhysical Education: DepedJeff FalconAinda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Research Paper About ObesityDocumento9 páginasResearch Paper About ObesityProsperoProllamante100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Final EssayDocumento12 páginasFinal EssayKayla RuppAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- 2nd QUARTER EXAMINATION IN P. E 2019-2020Documento3 páginas2nd QUARTER EXAMINATION IN P. E 2019-2020Lyzl Mahinay Ejercito MontealtoAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Effect of A Fruit and Vegetable Prescription Program On Children's Fruit and Vegetable ConsumptionDocumento13 páginasEffect of A Fruit and Vegetable Prescription Program On Children's Fruit and Vegetable ConsumptionKatie MerrittAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Factors Associated With Junk Food Consumption Among Urban School Students in Kathmandu District of NepalDocumento14 páginasFactors Associated With Junk Food Consumption Among Urban School Students in Kathmandu District of NepalSaurav ShresthaAinda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Community OSCE.Documento26 páginasCommunity OSCE.aaaskgamerAinda não há avaliações

- Reading and Writing Skills Module 1Documento18 páginasReading and Writing Skills Module 1shopia ibasitasAinda não há avaliações

- The Importance of BreakfastDocumento8 páginasThe Importance of Breakfastapi-284823421Ainda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Biology Notes Form 2 Teacher - Ac TZDocumento134 páginasBiology Notes Form 2 Teacher - Ac TZSamweliAinda não há avaliações

- Body Mass Index WorksheetDocumento2 páginasBody Mass Index WorksheetYasser EidAinda não há avaliações

- Ayurveda For Obesity - VikaspediaDocumento2 páginasAyurveda For Obesity - VikaspediaKRISHAinda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- 2020 f4 Science Notes KSSM Chapter 1 3Documento8 páginas2020 f4 Science Notes KSSM Chapter 1 3alanislnAinda não há avaliações

- HSB Group SBA3333Documento19 páginasHSB Group SBA3333Supreme King100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Irjet V7i61291Documento7 páginasIrjet V7i61291Rami ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- Pregnancy CounselingDocumento17 páginasPregnancy CounselingShannon WuAinda não há avaliações

- Malnutrition, - Frailty, - and - Sarcopenia - in - Patients. p1-p25 PDFDocumento34 páginasMalnutrition, - Frailty, - and - Sarcopenia - in - Patients. p1-p25 PDFRahma KhalafAinda não há avaliações

- Adult Nutrition Assessment Tutorial 2012Documento9 páginasAdult Nutrition Assessment Tutorial 2012Dariana floresAinda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- e-YDS Geçmiş Yıl Bütün SorularDocumento101 páginase-YDS Geçmiş Yıl Bütün Sorularberat karaca100% (3)

- Union, Ubay, Bohol English For Academic and Professional Purposes Summative Test 1 Quarter S.Y 2021-2022Documento4 páginasUnion, Ubay, Bohol English For Academic and Professional Purposes Summative Test 1 Quarter S.Y 2021-2022Ellesse Meigen Linog BoylesAinda não há avaliações

- Lifestyle and Weight Management-EditedDocumento26 páginasLifestyle and Weight Management-EditedkitcathAinda não há avaliações

- G9 PLATINUM SF8 Baseline Nutritional Status - 2022 - 2023Documento17 páginasG9 PLATINUM SF8 Baseline Nutritional Status - 2022 - 2023JERRYCO GARCIAAinda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Biology LabDocumento5 páginasBiology LabRuth-AnnLambertAinda não há avaliações