Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

1 Legislative Requirements - Introduction To Maritime Law

Enviado por

Jade Espiritu0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

61 visualizações84 páginasmaritime law

Título original

1 Legislative Requirements - Introduction to Maritime Law

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PPT, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentomaritime law

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PPT, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

61 visualizações84 páginas1 Legislative Requirements - Introduction To Maritime Law

Enviado por

Jade Espiritumaritime law

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PPT, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 84

LEGISLATIVE REQUIREMENTS

LO1. Explain the background of

maritime laws

Introduction to Maritime Law

Maritime law may be roughly divided into two

parts the commercial part and the

operational part.

When dealing with commercial maritime

law most of the law that has been embodied is

old customary law that is law that has been

followed through usage over a period of time.

These laws were framed maybe a century or

two ago by commercial trading houses like

Lloyds in their agreement for trade and

carriage of goods.

Newer versions always are incorporated in

them, these are frequently employed in the

bills of lading and the clauses may vary from

one bill of lading to the other.

However statute law is more rigid and has

been evolved for principally safety of the

persons employed on the ships further the

marine environment has been added to that

list.

A broad division may be made as statute

law harm to humans on the ship (today

inclusion of marine life).

Most of the statute laws are agreed upon

through the conventions between international

member states. The first of the convention

appeared over a century ago and dealt with

overloading of ships and towards the

collision between ships both arose over

excessive human life being lost.

The following header shows how a

Convention is adopted as a National Law in

a state.

In this case the Australian Parliament has

enacted the IBC as a law in Australia.

*The IBC Code provides an international

standard for the safe carriage by sea of

dangerous and noxious liquid chemicals in

bulk.

Begin Header

DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS

CANBERRA

Select Documents on International Affairs

No. 31 Volume II (1983) 2. page 105

Amendments to the International Convention

for the Safety of Life at Sea of 1 November

1974: International Code for the Construction

and Equipment of Ships carrying Dangerous

Chemicals in Bulk

(London, 17 June 1983)

Australian Government Publishing Service

Canberra, Commonwealth of Australia 2000

ADOPTION OF THE INTERNATIONAL

CODE FOR THE CONSTRUCTION AND

EQUIPMENT OF SHIPS CARRYING

DANGEROUS CHEMICALS IN BULK (IBC

CODE)

End Header

In this law the conventions have been

referenced to:

Begin Extract:

THE MERCHANT SHIPPING ACT, 1958

NO.44 OF 1958

[30th October, 1958]

An Act to foster the development and ensure

the efficient maintenance of an Indian

mercantile marine in a manner best suited to

seven the national interests and for that

purpose to established a National Shipping

Board and a Shipping Development Fund, to

provide for the registration of Indian ships and

generally to amend and consolidate the law

relating to merchant shipping.

Be it enacted by Parliament in the Ninth Year

of the Republic of India as follows:-

PART I

PARAMILITARY

1.Short title and commencement.- (1) This

Act may be called the Merchant Shipping Act,

1958.

3.Definitions.- In this Act, unless the context

otherwise requires,-

(3) collision regulations means the

regulations made under section 285 for the

prevention of collisions at sea;

(5) Country to which the Load Line

Convention applies means,-

(a) a country the Government of which has

been declared or is deemed to have been

declared under section 283 to have accepted

the Load Line Convention and has not been so

declared to have denounced that Convention;

(b) a country to which it has been so

declared that the Load Line Convention has

been applied under the provisions of article

twenty-one thereof, not being a country to

which it has been so declared that that

Convention has ceased to apply under the

provisions of that article;

(20) Load Line Convention means the

Convention signed in London on the 5th day of

July, 1930, for promoting safety of life and

property at sea, as amended from time to time;

(37) Safety Convention means the

Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea signed

in London on the 10th day of June 1949, as

amended from time to time;

End of extract

Since most of the coastal states and most of

the landlocked states indulging in global

trading and shipping are members of the UN,

therefore it is also a case where these

countries are also party to the various

conventions that are set up by the UN as

separate bodies.

An International convention once set up by

the UN goes into the specific matter on which

it has to deliberate, and after coming to a

conclusion taking into account the opinion

from the various member states and the

specialists in the field come out with the final

draft which is presented at the conference.

The member states are represented by their

official representatives and they put down their

countries as having been witnesses to the final

passing of the conference,

However this is just that the convention is

accepted. The representatives take the copies

of the conventions and the convention again

are scrutinized by the member stets experts in

the field as well as by legal and financial

experts.

Since the adoption could have meant a

variety of expenditure.

Once satisfied about the contents of the

convention the member state, enacts an act of

parliament which may give reference to the

convention or may publish the entire

convention as an act of parliament.

Thus this convention now becomes the low

of the land in that member state. The

information is passed on to the UN body and

the member state thus ratifies the convention.

Regarding disagreement on the clauses to

the convention the member state informs the

UN body about its reservations. If many such

reservations come in then the UN body may

ask for an overall look again in the convention.

Other repealing measures are as stated

below which is set out in the convention

document itself.

A sample of an international convention:

Please read the lines in bold. Wherein a state

is allowed the pleasure of agreeing to the local

unions requirement which may be contrary

to the convention but would be enhanced

from those of the convention.

Another part refers to the repealing of the

law/ convention by a member state after a

period of 10 years from the date of ratification.

Begin extract

ILO Convention (No. 180) concerning

Seafarers Hours of Work and the Manning of

Ships (Geneva, 22 October 1996)

THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF THE

INTERNATIONAL LABOUR ORGANIZATION,

HAVING BEEN CONVENED at Geneva by

the Governing Body of the International

Labour Office, and having met in its Eighty-

fourth Session on 8 October 1996, and,

NOTING the provisions of the Merchant

Shipping (Minimum Standards) Convention,

1976 and the Protocol of 1996 thereto; and the

Labour Inspection (Seafarers) Convention,

1996, and

RECALLING the relevant provisions of the

following instruments of the International

Maritime Organization:

1. International Convention for the Safety of

Life at Sea, 1974, as amended,

2. International Convention on Standards of

Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for

Seafarers, 1978, as amended in 1995,

3. Assembly resolution A481(XII)(1981) on

Principles of Safe Manning,

4. Assembly resolution A741(18)(1993) on

the International Code for the Safe Operation

of Ships and for Pollution Prevention

(International Safety Management (ISM)

Code), and

5. Assembly resolution A772(18)(1993) on

Fatigue Factors in Manning and Safety, and

RECALLING the entry into force of the

United Nations Convention on the Law of the

Sea, 1982, on 16 November 1994, and

HAVING DECIDED upon the adoption of

certain proposals with regard to the revision of

the Wages, Hours of Work and Manning (Sea)

Convention (Revised), 1958, and the Wages,

Hours of Work and Manning (Sea)

Recommendation, 1958, which is the second

item of the agenda of the session, and

HAVING DETERMINED that these proposals

shall take the form of an international

Convention;

ADOPTS , this twenty-second day day of

October of the year one thousand nine

hundred and ninety-six, the following

Convention, which may be cited as the

Seafarers Hours of Work and the Manning of

Ships Convention, 1996:

PART I

SCOPE AND DEFINITIONS

Article 1

1. This Convention applies to every seagoing

ship, whether publicly or privately owned,

which is registered in the territory of any

Member for which the Convention is in force

and is ordinarily engaged in commercial

maritime operations. For the purpose of this

Convention, a ship that is on the register of

two Members is deemed to be registered in

the territory of the Member whose flag it flies.

Article 4

A Member which ratifies this Convention

acknowledges that the normal working hours

standard for seafarers, like that for other

workers, shall be based on an eight-hour day

with one day of rest per week and rest on

public holidays. However, this shall not

prevent the Member from having

procedures to authorize or register a

collective agreement which determines

seafarers normal working hours on a basis

no less favourable than this standard.

6. Nothing in paragraphs 1 and 2 shall

prevent the Member from having national

laws or regulations or a procedure for the

competent authority to authorize or

register collective agreements permitting

exceptions to the limits set out. Such

exceptions shall, as far as possible, follow

the standards set out but may take account

of more frequent or longer leave periods or

the granting of compensatory leave for

watchkeeping seafarers or seafarers

working on board ships on short voyages.

FINAL PROVISIONS

1. This Convention shall be binding only

upon those Members of the International

Labour Organization whose ratifications have

been registered with the Director-General of

the International Labour Office.

2. This Convention shall come into force six

months after the date on which the ratifications

of five Members, three of which each have a

least one million gross tonnage of shipping,

have been registered with the Director-

General of the International Labour Office.

3. Thereafter, this Convention shall come into

force for any Member six months after the date

on which its ratification has been registered.

Article 19

1. A Member which has ratified this

Convention may denounce it after the

expiration of ten years from the date on which

the Convention first comes into force, by an

act communicated to the Director-General of

the International Labour Office for registration.

Such denunciation shall not take effect until

one year after the date on which it is

registered.

Article 20

1. The Director-General of the International

Labour Office shall notify all Members of the

International Labour Organization of the

registration of all ratifications and

denunciations communicated by the Members

of the Organization.

2. When the conditions provided for in Article

18, paragraph 2, above have been fulfilled, the

Director-General shall draw the attention of the

Members of the Organization to the date upon

which the Convention shall come into force.

Article 21

The Director-General of the International

Labour Office shall communicate to the

Secretary-General of the United Nations, for

registration in accordance with Article 102 of

the Charter of the United Nations, full

particulars of all ratifications and acts of

denunciation registered by the Director-

General in accordance with the provisions of

the preceding Articles.

Article 23

1. Should the Conference adopt a new

Convention revising this Convention in whole

or in part, then, unless the new Convention

otherwise provides-

(a) the ratification by a Member of the new

revising Convention shall ipso jure involve the

immediate denunciation of this Convention,

notwithstanding the provisions of Article 19

above, if and when the new revising

Convention shall have come into force;

(b) as from the date when the new revising

Convention comes into force, this Convention

shall cease to be open to ratification by the

Members.

2. This Convention shall in any case remain

in force in its actual form and content for those

Members which have ratified it but have not

ratified the revising Convention.

End extract

Maritime law is for worldwide trade. Trade is

between different states and as such claims

and such are always prevalent. If no common

ground existed then the dispute would not be

sorted out and the entire amicable trading

pattern would come to a standstill. Thus

conventions among member states are the

pillars on which international trade stands.

Once a convention has been accepted it sets

guideline at the very minimum the standards

that are to be associated for trade.

However a convention is only a guideline it is

not law of the land. To be so, the member

state has to get this convention enacted as a

law in its own country. Once this is done and

the country trades with another, which has at

its core law, a similar law based on the same

convention, the trading claims and others

proceed smoothly.

It must be remembered however that the law

being the same the penalties and other fines

may not be the same.

Also in addition to the law as per the

convention the state may have other laws,

which may not be similar to other state laws.

These conventions are all encompassing

and take into view all suggestions and after

clarifying the same are formulated. Thus the

convention is universally accepted and thus no

misunderstanding in the implementation

occurs. It becomes easier for member states

to trade knowing that the same convention is

applicable.

Any jurisdiction over other states properties

are set out in the convention itself the only

differing are the fines and the penalties which

are left to the individual states discretion

The main organizations involved in making

international laws:

1. United Nations

2. (UN Agency) International Maritime

Organization (IMO)

3. (UN Agency) International Labour

Organization (ILO)

4. (Organization of Maritime Laws) Comite

Maritime International (CMI)

Coastal State Jurisdiction

A. Criminal jurisdiction on board a foreign

ship

1. The criminal jurisdiction of the coastal

State should not be exercised on board a

foreign ship passing through the territorial sea

to arrest any person or to conduct any

investigation in connection with any crime

committed on board the ship during its

passage, save only in the following cases:

(a) if the consequences of the crime extend

to the coastal State;

(b) if the crime is of a kind to disturb the

peace of the country or the good order of the

territorial sea;

(c) if the assistance of the local authorities

has been requested by the master of the ship

or by a diplomatic agent or consular officer of

the flag State; or

(d) if such measures are necessary for the

suppression of illicit traffic in narcotic drugs or

psychotropic substances.

2. The above provisions do not affect the

right of the coastal State to take any steps

authorized by its laws for the purpose of an

arrest or investigation on board a foreign ship

passing through the territorial sea after

leaving internal waters.

3. In the cases provided for in paragraphs 1

and 2, the coastal State shall, if the master so

requests, notify a diplomatic agent or consular

officer of the flag State before taking any

steps, and shall facilitate contact between

such agent or officer and the ships crew.

In cases of emergency this notification may be

communicated while the measures are being

taken.

4. In considering whether or in what manner

an arrest should be made, the local authorities

shall have due regard to the interests of

navigation.

5. The coastal State may not take any steps

on board a foreign ship passing through the

territorial sea to arrest any person or to

conduct any investigation in connection with

any crime committed before the ship entered

the territorial sea, if the ship, proceeding from

a foreign port, is only passing through the

territorial sea without entering internal waters.

B. Civil jurisdiction in relation to foreign ships

1. The coastal State should not stop or

divert a foreign ship passing through the

territorial sea for the purpose of exercising civil

jurisdiction in relation to a person on board the

ship.

2. The coastal State may not levy execution

against or arrest the ship for the purpose of

any civil proceedings, save only in respect of

obligations or liabilities assumed or incurred

by the ship itself in the course or for the

purpose of its voyage through the waters of

the coastal State.

3. Paragraph 2 is without prejudice to the

right of the coastal State, in accordance with

its laws, to levy execution against or to arrest,

for the purpose of any civil proceedings, a

foreign ship lying in the territorial sea, or

passing through the territorial sea after leaving

internal waters.

C. Port State control on operational

requirements

1. A ship when in a port of another

Contracting Government is subject to control

by officers duly authorized by such

Government concerning operational

requirements in respect of the safety of ships,

when there are clear grounds for believing that

the Master or crew are not familiar with

essential shipboard procedures relating to the

safety of ships.

2. In the circumstances defined in paragraph

1 of this regulation, the Contracting

Government carrying out the control shall take

such steps as will ensure that the ship shall

not sail until the situation has been brought to

order in accordance with the requirements of

the present Convention.

3. Procedures relating to the port State

control prescribed in regulation I/19 shall apply

to this regulation.

4. Nothing in the present regulation shall be

construed to limit the rights and obligations of

a Contracting Government carrying out control

over operational requirements specifically

provided for in the regulations.

D. Control

(a) Every ship when in a port of another

Contracting Government is subject to control

by officers duly authorized by such

Government in so far as this control is directed

towards verifying that the certificates issued

under regulation 12 or regulation 13 are valid.

(b) Such certificates, if valid, shall be

accepted unless there are clear grounds for

believing that the condition of the ship or of its

equipment does not correspond substantially

with the particulars of any of the certificates or

that the ship and its equipment are not in

compliance with the regulation.

(c) In the circumstances or where a

certificate has expired or ceased to be valid,

the officer carrying out the control shall take

steps to ensure that the ship shall not sail until

it can proceed to sea or leave the port for the

purpose of proceeding to the appropriate

repair yard without danger to the ship or

persons on board.

(d) In the event of this control giving rise to

an intervention of any kind, the officer carrying

out the control shall forthwith inform, in writing,

the Consul or, in his absence, the nearest

diplomatic representative of the State whose

flag the ship is entitled to fly of all the

circumstances in which intervention was

deemed necessary. In addition, nominated

surveyors or recognized organizations

responsible for the issue of the certificates

shall also be notified.

The facts concerning the intervention shall

be reported to the Organization.

(e) The port State authority concerned shall

notify all relevant information about the ship to

the authorities of the next port of call, in

addition to parties mentioned, if it is unable to

take action as specified or if the ship has been

allowed to proceed to the next port of call.

(f) When exercising control under this

regulation all possible efforts shall be made to

avoid a ship being unduly detained or delayed.

If a ship is thereby unduly detained or delayed

it shall be entitled to compensation for any

loss or damage suffered.

Relevant IMO Conventions

1. International Convention for the Safety

of Life at Sea (SOLAS), 1974

Adoption: 1 November 1974; Entry into

force: 25 May 1980

The SOLAS Convention in its successive

forms is generally regarded as the most

important of all international treaties

concerning the safety of merchant ships. The

first version was adopted in 1914, in response

to the Titanic disaster, the second in 1929, the

third in 1948, the fourth in 1960 and the fifth in

1974.

The main objective of the SOLAS

Convention is to specify minimum standards

for the construction, equipment and operation

of ships, compatible with their safety. Flag

States are responsible for ensuring that ships

under their flag comply with its requirements,

and a number of certificates are prescribed in

the Convention as proof that this has been

done.

Control provisions also allow Contracting

Governments to inspect ships of other

Contracting States if there are clear grounds

for believing that the ship and its equipment do

not substantially comply with the requirements

of the Convention - this procedure is known as

port State control. The current SOLAS

Convention includes Articles setting out

general obligations, amendment procedure

and so on, followed by an Annex divided into

12 Chapters.

2. International Convention for the

Prevention of Pollution from Ships

(MARPOL 73/78)

Adoption: 1973 (Convention), 1978 (1978

Protocol), 1997 (Protocol - Annex VI); Entry

into force: 2 October 1983 (Annexes I and II).

MARPOL 73/78 is the main international

convention covering prevention of pollution of

the marine environment by ships from

operational or accidental causes.

The MARPOL Convention was adopted on 2

November 1973 at IMO. The Protocol of 1978

was adopted in response to a spate of tanker

accidents in 1976-1977. As the 1973 MARPOL

Convention had not yet entered into force, the

1978 MARPOL Protocol absorbed the parent

Convention. The combined instrument entered

into force on 2 October 1983. In 1997, a

Protocol was adopted to amend the

Convention and a new Annex VI was added

which entered into force on 19 May 2005.

MARPOL has been updated by amendments

through the years.

The Convention includes regulations aimed

at preventing and minimizing pollution from

ships - both accidental pollution and that from

routine operations - and currently includes six

technical Annexes. Special Areas with strict

controls on operational discharges are

included in most Annexes.

MARPOL ANNEXES

1. Annex I Regulations for the Prevention

of Pollution by Oil (entered into force 2

October 1983) Covers prevention of pollution

by oil from operational measures as well as

from accidental discharges; the 1992

amendments to Annex I made it mandatory for

new oil tankers to have double hulls and

brought in a phase-in schedule for existing

tankers to fit double hulls, which was

subsequently revised in 2001 and 2003.

2. Annex II Regulations for the Control of

Pollution by Noxious Liquid Substances in Bulk

(entered into force 2 October 1983) details the

discharge criteria and measures for the control of

pollution by noxious liquid substances carried in bulk;

some 250 substances were evaluated and included

in the list appended to the Convention; the discharge

of their residues is allowed only to reception facilities

until certain concentrations and conditions (which

vary with the category of substances) are complied

with. In any case, no discharge of residues

containing noxious substances is permitted within 12

miles of the nearest land.

3. Annex III Prevention of Pollution by

Harmful Substances Carried by Sea in

Packaged Form (entered into force 1 July

1992) contains general requirements for the

issuing of detailed standards on packing,

marking, labelling, documentation, stowage,

quantity limitations, exceptions and notifications.

For the purpose of this Annex, harmful

substances are those substances which are

identified as marine pollutants in the International

Maritime Dangerous Goods Code (IMDG Code)

or which meet the criteria in the Appendix of

Annex III.

4. Annex IV Prevention of Pollution by Sewage

from Ships (entered into force 27 September

2003) contains requirements to control pollution of

the sea by sewage; the discharge of sewage into the

sea is prohibited, except when the ship has in

operation an approved sewage treatment plant or

when the ship is discharging comminuted and

disinfected sewage using an approved system at a

distance of more than three nautical miles from the

nearest land; sewage which is not comminuted or

disinfected has to be discharged at a distance of

more than 12 nautical miles from the nearest land.

In July 2011, IMO adopted the most recent

amendments to MARPOL Annex IV which are

expected to enter into force on 1 January

2013. The amendments introduce the Baltic

Sea as a special area under Annex IV and add

new discharge requirements for passenger

ships while in a special area.

5. Annex V Prevention of Pollution by Garbage

from Ships (entered into force 31 December 1988)

deals with different types of garbage and specifies

the distances from land and the manner in which

they may be disposed of; the most important feature

of the Annex is the complete ban imposed on the

disposal into the sea of all forms of plastics.

In July 2011, IMO adopted extensive amendments

to Annex V which are expected to enter into force on

1 January 2013. The revised Annex V prohibits the

discharge of all garbage into the sea, except as

provided otherwise, under specific circumstances.

6. Annex VI Prevention of Air Pollution from

Ships (entered into force 19 May 2005) sets

limits on sulphur oxide and nitrogen oxide emissions

from ship exhausts and prohibits deliberate

emissions of ozone depleting substances;

designated emission control areas set more stringent

standards for SOx, NOx and particulate matter.

In 2011, after extensive work and debate, IMO

adopted ground breaking mandatory technical and

operational energy efficiency measures which will

significantly reduce the amount of greenhouse gas

emissions from ships; these measures were included

in Annex VI and are expected to enter into force on 1

January 2013.

With respect to ships entitled to fly the flag of

a State which is not a Party to the Convention

and the present Protocol, the Parties to the

present Protocol shall apply the requirements

of the Convention and the present Protocol as

may be necessary to ensure that no more

favourable treatment is given to such ships.

This means that whether or not a ship flies

the flag of a signatory country or not, it shall be

subject to all the conditions of as applicable

under this convention. Thus a ship would not

be permitted to enter a signatory countrys

waters in a substandard condition and give an

excuse that her government is not a signatory,

hence she is outside the jurisdiction of

complying with the conditions of this protocol.

Rules of Convention to Law

Almost everything we do is governed by

some set of rules. There are rules for games,

for social clubs, for sports and for adults in the

workplace. There are also rules imposed by

morality and custom that play an important

role in telling us what we should and should

not do.

However, some rulesthose made by the

state or the courtsare called laws.

Laws resemble morality because they are

designed to control or alter our behaviour. But

unlike rules of morality, laws are enforced by

the courts; if you break a lawwhether you

like that law or notyou may be forced to pay

a fine, pay damages, or go to prison.

Since individuals began to associate with

other peopleto live in societylaws have

been the glue that has kept society together.

Laws regulating our business affairs help to ensure

that people keep their promises. Laws against

criminal conduct help to safeguard our personal

property and our lives.

Even in a well-ordered society, people have

disagreements and conflicts arise. The law must

provide a way to resolve these disputes peacefully.

We need law, then, to ensure a safe and peaceful

society in which individuals rights are respected.

The law is a set of rules for society, designed to

protect basic rights and freedoms, and to treat

everyone fairly.

These rules can be divided into two basic

categories:

1. Public Law

Public law deals with matters that affect

society as a whole. It includes areas of the law

that are known as criminal, constitutional and

administrative law. These are the laws that

deal with the relationship between the

individual and the state, or among

jurisdictions.

2. Private Law

Private law, on the other hand, deals with the

relationships between individuals in society

and is used primarily to settle private disputes.

Private law deals with such matters as

contracts, the rights and obligations of family

members, and damage to ones person or

property caused by others. When one

individual sues another over some private

dispute, this is a matter for private law.

Private International Law is the body of

conventions, model laws, legal guides, and

other documents and instruments that regulate

private relationships across national borders.

Private international law has a dualistic

character, balancing international consensus

with domestic recognition and implementation,

as well as balancing sovereign actions with

those of the private sector.

The law of the land which finally is enforcer

for the conventions ensures that the law

(convention) is enforced by ensuring that

before any certification is done the ship are

surveyed, and after this only are they certified.

The surveys are as per the code or may be

as per the law of that state however they

cannot fall below the standard as set out in the

convention.

As far as possible these details are to be

inspected and then certified. These then

become as authorized by the government of

that state and are seen as official documents.

The government agencies (may be various)

are entrusted by the state to enforce the law/

convention in the nature of any violation be it

by way of area violation, pollution or by way of

improper certification

Thus for any violation a ship may be

detained for a short period or for long. May be

fined and personnel may be imprisoned.

The government agencies are also the

keeper of all records since the state has to

submit to the IMO all records regarding any

detention and other cases of violation,

including all dispensations granted.

From the above it may be observed that it is

of utmost importance to study the national

legislation that has been adapted in view to

the conventions and also any other rules and

regulations that may have been enacted for

maritime convenience.

Additionally the rules and regulations of the

port state in which the ship arrives may have a

set of different rules and regulations which the

ship would have to observe.

These set of rules and regulations are

generally passed onto to the ship through

either the pilot or the agent to the ship. Any

notification may also be available from other

sources. It is not mandatory for the ship to

have received the notice of any extra rules and

regulation through oversight of the agent or

others, if the law has been published and

informed to other places then it is supposed to

have been informed to the ship.

Thus the ship cannot say that since it has not

received that it would assume it has not been

informed and thus would fail to comply,

It is the duty of the ship through the company

and the agents to keep abreast of all new laws

and regulations that may affect the ship and

the crew when arriving into any state to which

the port belongs.

Você também pode gostar

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Top 10 Chart PatternsDocumento25 páginasTop 10 Chart Patternsthakkarps50% (2)

- Chinese Erotic Art by Michel BeurdeleyDocumento236 páginasChinese Erotic Art by Michel BeurdeleyKina Suki100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- 40 Days of ProsperityDocumento97 páginas40 Days of ProsperityGodson100% (3)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Forex 4 UDocumento25 páginasForex 4 US N Gautam100% (2)

- Helena Monolouge From A Midsummer Night's DreamDocumento2 páginasHelena Monolouge From A Midsummer Night's DreamKayla Grimm100% (1)

- Studying Religion - Russell McCutcheonDocumento15 páginasStudying Religion - Russell McCutcheonMuhammad Rizal100% (1)

- Power Sector OutlookDocumento5 páginasPower Sector OutlookJade EspirituAinda não há avaliações

- Instructor'S GuideDocumento9 páginasInstructor'S GuideJade EspirituAinda não há avaliações

- NROTC 3cl 1st AssignDocumento3 páginasNROTC 3cl 1st AssignJade EspirituAinda não há avaliações

- POODocumento12 páginasPOOJade EspirituAinda não há avaliações

- A Poem For MomDocumento1 páginaA Poem For MomJade EspirituAinda não há avaliações

- DebateDocumento2 páginasDebateJade EspirituAinda não há avaliações

- E Nav TopicsDocumento202 páginasE Nav TopicsJade EspirituAinda não há avaliações

- SOLAR SYSTEM ExplanationDocumento2 páginasSOLAR SYSTEM ExplanationJade EspirituAinda não há avaliações

- Geol SamplexDocumento7 páginasGeol SamplexJade EspirituAinda não há avaliações

- Geol SamplexDocumento7 páginasGeol SamplexJade EspirituAinda não há avaliações

- AASlabmanualDocumento54 páginasAASlabmanuallkomninos2221Ainda não há avaliações

- MSME - Pratham Heat TreatmentDocumento2 páginasMSME - Pratham Heat TreatmentprathamheattreatmentAinda não há avaliações

- Mita Lifestyle Agenda ContentDocumento263 páginasMita Lifestyle Agenda Contentnacentral13517Ainda não há avaliações

- Manpower Planning, Recruitment and Selection AssignmentDocumento11 páginasManpower Planning, Recruitment and Selection AssignmentWEDAY LIMITEDAinda não há avaliações

- Compiled Reports From 57th JCRC AY1314Documento44 páginasCompiled Reports From 57th JCRC AY1314keviiagm1314Ainda não há avaliações

- Family View - Printer Friendly - Ancestry - co.UkPt1Documento4 páginasFamily View - Printer Friendly - Ancestry - co.UkPt1faeskeneAinda não há avaliações

- CV - Mai Trieu QuangDocumento10 páginasCV - Mai Trieu QuangMai Triệu QuangAinda não há avaliações

- Ebook PDF Data Mining For Business Analytics Concepts Techniques and Applications With Xlminer 3rd Edition PDFDocumento41 páginasEbook PDF Data Mining For Business Analytics Concepts Techniques and Applications With Xlminer 3rd Edition PDFpaula.stolte522100% (35)

- Homework 4題目Documento2 páginasHomework 4題目劉百祥Ainda não há avaliações

- The Teaching ProfessionDocumento18 páginasThe Teaching ProfessionMary Rose Pablo ♥Ainda não há avaliações

- Criteria O VS S F NI Remarks: St. Martha Elementary School Checklist For Classroom EvaluationDocumento3 páginasCriteria O VS S F NI Remarks: St. Martha Elementary School Checklist For Classroom EvaluationSamantha ValenzuelaAinda não há avaliações

- Drdtah: Eticket Itinerary / ReceiptDocumento8 páginasDrdtah: Eticket Itinerary / ReceiptDoni HidayatAinda não há avaliações

- Our Official Guidelines For The Online Quiz Bee Is HereDocumento3 páginasOur Official Guidelines For The Online Quiz Bee Is HereAguinaldo Geroy JohnAinda não há avaliações

- Reviewer For Fundamentals of Accounting and Business ManagementDocumento4 páginasReviewer For Fundamentals of Accounting and Business ManagementAngelo PeraltaAinda não há avaliações

- StarBucks (Case 7)Documento5 páginasStarBucks (Case 7)Александар СимовAinda não há avaliações

- Multiple Compounding Periods in A Year: Example: Credit Card DebtDocumento36 páginasMultiple Compounding Periods in A Year: Example: Credit Card DebtnorahAinda não há avaliações

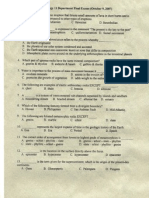

- JHCSC Dimataling - Offsite Class 2 Semester 2021 Summative TestDocumento1 páginaJHCSC Dimataling - Offsite Class 2 Semester 2021 Summative TestReynold TanlangitAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To The Philosophy of The Human Person Lesson 3 - The Human PersonDocumento5 páginasIntroduction To The Philosophy of The Human Person Lesson 3 - The Human PersonPaolo AtienzaAinda não há avaliações

- Social Quotation EIA Study Mumbai MetroDocumento12 páginasSocial Quotation EIA Study Mumbai MetroAyushi AgrawalAinda não há avaliações

- Eir SampleDocumento1 páginaEir SampleRayrc Pvt LtdAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 11 - Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis: A Managerial Planning ToolDocumento19 páginasChapter 11 - Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis: A Managerial Planning ToolSkyler LeeAinda não há avaliações

- Flinn (ISA 315 + ISA 240 + ISA 570)Documento2 páginasFlinn (ISA 315 + ISA 240 + ISA 570)Zareen AbbasAinda não há avaliações

- CPDD-ACC-02-A Application Form As Local CPD ProviderDocumento2 páginasCPDD-ACC-02-A Application Form As Local CPD Providerattendance.ceacAinda não há avaliações

- Group 1 KULOT RevisedDocumento15 páginasGroup 1 KULOT RevisedFranchesca Mekila TuradoAinda não há avaliações

- AMGPricelistEN 09122022Documento1 páginaAMGPricelistEN 09122022nikdianaAinda não há avaliações

- Aditya DecertationDocumento44 páginasAditya DecertationAditya PandeyAinda não há avaliações

- Ch.3 Accounting of Employee Stock Option PlansDocumento4 páginasCh.3 Accounting of Employee Stock Option PlansDeepthi R TejurAinda não há avaliações