Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Geometric Style: Iliad and The Odyssey But The Visual Art of This Period

Enviado por

audreypillow100%(1)100% acharam este documento útil (1 voto)

553 visualizações23 páginasGreek art of this period does not hint at the accomplishment and power of the epics. Orientalizing Style By about 700 BC new motifs began to appear. The major areas are given over to storytelling and figurative representation of heroes, gods, monsters.

Descrição original:

Título original

Greek Art

Direitos autorais

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

PPT, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoGreek art of this period does not hint at the accomplishment and power of the epics. Orientalizing Style By about 700 BC new motifs began to appear. The major areas are given over to storytelling and figurative representation of heroes, gods, monsters.

Direitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PPT, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

100%(1)100% acharam este documento útil (1 voto)

553 visualizações23 páginasGeometric Style: Iliad and The Odyssey But The Visual Art of This Period

Enviado por

audreypillowGreek art of this period does not hint at the accomplishment and power of the epics. Orientalizing Style By about 700 BC new motifs began to appear. The major areas are given over to storytelling and figurative representation of heroes, gods, monsters.

Direitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PPT, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 23

Geometric Style

• At first, Geometric pottery was decorated only with

abstract designs, but toward 800 BC humans and

animals began to appear

• This is the Dipylon vase, c. 750 BC, from the Dipylon

cemetery

• Belongs to a group of very large vases that served as

grave monuments

• On the body of the vase we see the dead man lying in

state, flanked my mourning figures; below is a funeral

procession

• The width, density, and spacing of the bands are subtly

related to the vessel, but interest in representation is

minimal

• The figures are highly stylized and repeated at regular

intervals; this is a silhouette style that cannot

accommodate overlapping

• The figures merge into an overall decorative pattern

• During this era, the two greatest Greek artistic

achievements were the Homeric epics in literature, the

Iliad and the Odyssey; but the visual art of this period

does not hint at the accomplishment and power of those

poems. During this period, painting and sculpture has

not developed as much as poetry; the Geometric style is

highly formulaic and mostly funerary

Orientalizing Style

• By about 700 BC new motifs began to appear and Greek

art entered a new phase, the profoundly transforming

Orientalizing style, which looks to Egypt and the Near

East

• Represents a new monumentality and variety with much

experimentation

• This is a large amphora (vase for storing wine or oil)

from Eleusis: The Blinding of Polyphemos and the

Gorgons Chasing Perseus

• Compared to the Dipylon Vase: ornamentation is

secondary; the major areas are given over to storytelling

and figural representation of heroes, gods, monsters

• This shows the blinding of the giant one-eyed Cyclops

Polythemos by Odysseus and his companions, who the

giant had imprisoned

• The slaying of another monstrous creature is depicted on

the belly of the vase but it has been damaged; we see

only two figures, the gorgons (sisters of Medusa), and

the goddess Athena

• Two technical advances during this time: outline

drawing and incision (scratching in details with a

needle; this allows the artist to create overlappings and

interior lines to delineate anatomy, dress, hair, etc

Archaic Style

•Orientalizing period was transitional; as artists assimilated elements from

the East, the Archaic style emerged; in this era we see the unfolding of the

artistic genius of Greece, not only in vase painting but in architecture and

sculpture

•Archaic vase painting introduces signatures of artists, distinctive artists’

styles and some of the first clearly defined personalities in the history of

art; this was the great era of vase painting

•This vase represents the black figure technique, in which the entire

design is silhouetted in black against the reddish clay and all internal

details are incised; this technique favors a layered, two-dimensional effect

that complements the curvature of the vase

•This vase by Psiax, Herkales Strangling the Nemean Lion, c.525 BC,

shows a man facing unknown forces in the form of terrifying creatures; it

is grim and violent, with heavy bodies locked in combat, almost merging

into a single unit

•:Lines and colors have been added with the utmost economy to avoid

breaking up the massive expanse of black, yet the figures show a wealth

of anatomical knowledge and skillful foreshortening that they give an

illusion of existing in the round

•Only in details such as the eye of Herkales do we still find the traditional

combination of front and profile views

•This style was not confined to vases; there were murals and panels too

but none survive today

Red-figure technique

• This gradually replaced the older black-

figure method toward 500 BC

• This is a krater for mixing wine by

Euphronios, Herkales Wrestling Antaios

• In this style, interior lines are not

incised but were applied with a nozzle

(like a cake icer) or a brush; the artist

depends less on the profile view than

before

• He uses interior lines to show boldly

foreshortened and overlapping limbs,

costume details, and facial expressions

• Figures are as large as possible, and

these details allow the artist to explore a

new world of feeling: we see suffering,

pain and fear

Classical Style

• According to literary sources, Greek mural painters of this period, which

began about 480 BC, achieved major breakthroughs in creating an illusion

of spacial depth or perspective, scenes of real dramatic power, and

vigorous studies of human character and emotion. This gradually

transformed vase painting into a minor art.

• Greek painting reached its peak in the fourth century BC with the invention

of the picture for display on an easel or wall

• Roman frescoes and mosaics give us an idea of what these looked like, but

are not always reliable

• The following slide, Battle of Alexander and the Persians, is probably a

later Roman copy of an early Hellenistic painting of 330-300 BC

• Follows four-color scheme (yellow, red, black, white); foreshortening and

precise shadows make this far more complicated and dramatic than

anything we’ve seen so far; it is a realistic depiction of a historical event

Temples

• Creation of large freestanding temples began in late

Geometric period; from about 600 BC cut stone was

used throughout except for the roof

• The temple is essentially a weather-proof statue box,

intended to house the statue of a deity worshipped there

• Greek temple architecture is one of the most important

legacies to Western art

• Parts of a Greek temple (required)

• If you have the textbook, review “Reading

Architectural Drawings” (p. 79)

Orders

• Greek architecture is identified with the three Classical orders: Doric, Ionic,

and Corinthian (the third is a variant of the Ionic)

• An architectural order is a distinct and consistent architectural style; this term

is only used for Greek architecture and its descendants

• The orders are sets of generally accepted conventions, ensuring that the

elements of the two orders remained extraordinarily constant in kind, number,

and relation to one another

• Each temple is governed by a structural logic that makes it look stable and

satisfying because of the precise arrangement of its parts; it shows and internal

consistency, harmony, and balance

• The Greek orders place a premium on design in architecture (as opposed to

mere building); symmetry and proportion are paramount

• More on the Greek Orders (required)

Temples of Hera I and II

• Hera I (here): c. 550 BC; Hera II (next slide):

c.460 BC, Paesturm, Italy (a former Greek

colony)

• Dedicated to goddess Hera, wife of Zeus

• Both temples are Doric but bear striking

differences in their proportions

• Hera I is low and sprawling; Hera II looks tall and

compact

• The columns at Hera I are more strongly curved

and tapered to a relatively narrow top. This

swelling effect, called entasis, makes one feel that

the columns bulge with the strain of supporting

the structure

• In the columns at Hera II the exaggerated

curvature has been modified: the columns are

taller and the capitals are more compact;

combined with wider column spacing, there is a

more harmonious balance

The Parthenon

• Sits on the Akropolis (also

Acropolis, literally “high city”),

the sacred hill above Athens

• The greatest temple on this hill

is the Parthenon, dedicated to

the goddess Athena, Athens’

patron deity

• Embodiment of Classical Doric

architecture; built of white

marble

• More about the Parthenon

(required)

The Propylea

• Is the monumental entry

gate to the Western end of

the Akropolis

• Also built of marble

• Features proportions and

refinements similar to the

Parthenon, but on a

steeply rising site

Archaic Sculpture

• Kouros (Standing Youth), c . 580 BC, marble

• Compared with Egyptian statue of Menkaure,

they share a block-conscious quality, both

stand with left leg forward, both planned on a

grid and very formal

• But the Kouros is truly freestanding; it is the

earliest large stone image of the human art of

which this can be said. Arms are separated

from the torso and legs from each other; the

carver cuts away the rest of the stone (only

exception is the bridges between fists and

thighs).

• Earlier sculptures remain immersed in the

stone, empty spaces between forms remain

partly filled)

• This kore (as the female Greek statue is

called) is more varied than the kouros,

because it is clothed

• Poses the problem of relating body and

drapery; more likely to reflect changing

habits and local differences in dress

• This Kore in Ionian Dress (c. 520 BC,

marble) was made almost a century after

the Kouros on the last slide

• Wears symmetrical linen gown (chiton)

over a heavy assymetrical woolen cloak

(or himmation) beneath

• Folds are highly stylized

• Strong face with mannish face but

characteristic smile and soft tresses that

fall to the shoulders and softly model the

breasts

• Kouros (“male youth”) and kore

(“maiden”) sculptures gernerally represent

youth, vitality and happiness

Architectural Sculpture

• Greek temples were designed with sculpture

in mind

• Stone sculpture in temples is mostly confined

to the pediment between the ceiling and

roof, and to the zone below (although Ionians

would sometimes support the roof of a porch

with female statues called caryatids instead

of columns)

• The Battle of the Gods and Giants (north

frieze of the Treasury of the Siphnians at

Delphi), c. 530 BC is executed in very high

relief with deep undercutting; sculptor has

taken advantage of the spatial possibilities

here

• Arms and legs nearest the viewer are carved

completely in the round

• This is a condensed but convincing space that

permits a more dramatic relationship between

the figures than we have ever seen before in

narrative reliefs

Classical Style Sculpture

• Kritios Boy, c 480 BC, marble

• Figure stands “at ease” due to a stance

called contraposto (or counterpoise);

balancing weight-bearing and free,

tensed and relaxed, bringing about

subtle displacements; these make it

seem more “alive”

• See video excerpt of BBC's "How Art

Made the World” (required) for a

discussion of this sculpture as well as

later refinements

• Zeus, c. 460 BC,

Bronze, almost 7 ft tall

• His physique is a

mature version of the

Kritios Boy,

powerfully defined and

massive, expressing

the god’s cosmic

power

• Doryphoros (Spear

Bearer), modern

reconstruction of original

of c. 440 BC by

Polykleitos

• Now the tense and relaxed

limbs are more sharply

and clearly differentiated;

turn of the head more

pronounced

• A “perfect” model and

sculptural prototype of the

Greek canon

• More on the Doryphoros

here (required)

Classical Sculpture

• Three Goddesses, from the east

pediment of the Parthenon, c. 438-

432 BC, marble, over life-size

• In fragmentary condition, now

housed in the British Museum (part

of the group of works known as the

Elgin Marbles)

• Represents various female deities

in sitting and reclining poses;

depicts ease of movement even in

repose

• No specific action, violence or

pathos - just a “deeply felt poetry

of being”; thin, “wet-look” drapery

of costume

Hellenistic Sculpture

• Came after Classical period;

generally even more realistic

and expressive but at times

contrived or even contorted

• Epignonos of Pergamon (?),

Dying Trumpter, Roman copy

after a bronze original of c. 200

BC; over 6 ft tall

• This Celtic trumpeter (the

Greeks’ enemy) has been fatally

wounded in the chest in battle

• Depicts a great deal of ethnic

detail, dignity and pathos

• Pythokritos of Rhodes

(?), Nike of

Samothrace, c. 190

BC

• Greatest surviving

masterpiece of

Hellenistic sculpture

• About this sculpture

(required)

• Portrait Head from Delos, c.

100 BC, bronze

• Once part of a full-length

statue; man’s identity is not

known

• Fluid modeling of somewhat

flabby features, uncertain

mouth, and unhappy eyes

under furrowed brows reveal

doubt and fear; this is far from

the heroic perfection of the

Classical period

Você também pode gostar

- Greek Sculpture: A Collection of 16 Pictures of Greek Marbles (Illustrated)No EverandGreek Sculpture: A Collection of 16 Pictures of Greek Marbles (Illustrated)Ainda não há avaliações

- ARTID111-Ancient Greek ArtDocumento109 páginasARTID111-Ancient Greek ArtarkioskAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient Greek Art: What Do You Know About Life in Ancient Greece?Documento39 páginasAncient Greek Art: What Do You Know About Life in Ancient Greece?L. Syajvo100% (1)

- Art History Ancient GreeceDocumento34 páginasArt History Ancient GreeceCrisencio M. PanerAinda não há avaliações

- Final Part 1 - Historical Development of ArtDocumento254 páginasFinal Part 1 - Historical Development of ArtMarianne CoracheaAinda não há avaliações

- Greek VasesDocumento64 páginasGreek VasesDinos Gonatas100% (2)

- Ancient Greek ArtDocumento70 páginasAncient Greek ArtRyan McLay100% (3)

- Understanding Greek Vases PDFDocumento172 páginasUnderstanding Greek Vases PDFSaymon Almeida100% (7)

- Ancient Greek ArtDocumento36 páginasAncient Greek ArtMarkabelaMihaela100% (1)

- The Art of Ancient GreeceDocumento56 páginasThe Art of Ancient Greecelostpurple2061100% (4)

- Greek Art (Fifth Edition 2016) by JOHN BOARDMAN PDFDocumento750 páginasGreek Art (Fifth Edition 2016) by JOHN BOARDMAN PDFCristianStaicu100% (7)

- Greek Art PDFDocumento31 páginasGreek Art PDFManish Sharma100% (5)

- Ancient Greek ArchitectureDocumento21 páginasAncient Greek ArchitectureNykha Alenton100% (2)

- Renaissance Art BookletDocumento20 páginasRenaissance Art Bookletfrancesplease100% (1)

- Egyptian Forms of ArtDocumento32 páginasEgyptian Forms of ArtMona JhangraAinda não há avaliações

- Greek ArchitectureDocumento47 páginasGreek Architecturenaveenarora298040100% (3)

- ARTID111-Ancient Egyptian Art Part 1Documento91 páginasARTID111-Ancient Egyptian Art Part 1arkiosk100% (1)

- Prehistoric ArtDocumento37 páginasPrehistoric Artholocenic100% (2)

- JENNIFER - Tobin) - The - Glory - That - Was - Greece - GREEK ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY PDFDocumento65 páginasJENNIFER - Tobin) - The - Glory - That - Was - Greece - GREEK ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY PDFathanasios1940B100% (1)

- Hoa1 (6) Greek PDFDocumento70 páginasHoa1 (6) Greek PDFAnne Margareth Dela CruzAinda não há avaliações

- Greek ArchitectureDocumento35 páginasGreek Architecturesugunaprem100% (1)

- Greek Funerary SculptureDocumento174 páginasGreek Funerary SculptureEleftheria Psoma100% (8)

- Greek Art (World of Art Ebook)Documento256 páginasGreek Art (World of Art Ebook)Fran HrzicAinda não há avaliações

- Roman Art (750 BCE - 200 CE) : Etruscan-Style Paintings and SculpturesDocumento4 páginasRoman Art (750 BCE - 200 CE) : Etruscan-Style Paintings and SculpturesAkash Kumar SuryawanshiAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient Near East ArtDocumento79 páginasAncient Near East ArtRyan McLayAinda não há avaliações

- Greek ArchitectureDocumento24 páginasGreek ArchitectureArchitect AejazAinda não há avaliações

- Timeline of Western ArchitectureDocumento17 páginasTimeline of Western ArchitectureLorna GrayAinda não há avaliações

- Greek ArtsDocumento39 páginasGreek Artsspongebob squarepantsAinda não há avaliações

- Art of Ancient EgyptDocumento5 páginasArt of Ancient EgyptAdamWorthAinda não há avaliações

- Greek ArchitectureDocumento60 páginasGreek Architecturenenna100% (2)

- Roman Art, New YorkDocumento218 páginasRoman Art, New YorkCatinca Iunia Stoian100% (7)

- Greek Art and Archaeology, 5th Edition PDFDocumento403 páginasGreek Art and Archaeology, 5th Edition PDFSoti100% (25)

- Romanesque ArchitectureDocumento13 páginasRomanesque ArchitectureSam_Dichoso_4540100% (2)

- Asian ArtDocumento49 páginasAsian ArtTala YoungAinda não há avaliações

- History of Roman ArchitectureDocumento37 páginasHistory of Roman ArchitectureAratrika Bhagat100% (7)

- A Handbook of Roman Art PDFDocumento322 páginasA Handbook of Roman Art PDFEmily90% (10)

- Apollo - An Illustrated Manual of The History of Art Throughout The Ages (Reinach 1907) GDocumento369 páginasApollo - An Illustrated Manual of The History of Art Throughout The Ages (Reinach 1907) Gtayl5720Ainda não há avaliações

- Greek Architecture: (Types of Buildings)Documento73 páginasGreek Architecture: (Types of Buildings)Sneaky KimAinda não há avaliações

- The Roman Art: by Group IDocumento58 páginasThe Roman Art: by Group IRowie Ann TapiaAinda não há avaliações

- National Archaeological Museum, AthensDocumento176 páginasNational Archaeological Museum, Athenslouloudos1100% (8)

- From Athens To Naukratis: Iconography of Black-Figure ImportsDocumento40 páginasFrom Athens To Naukratis: Iconography of Black-Figure ImportsDebborah DonnellyAinda não há avaliações

- Arts Style: Doric Column Ionic-Column Corinthian ColumnDocumento5 páginasArts Style: Doric Column Ionic-Column Corinthian ColumnKiller FranzAinda não há avaliações

- CH3 Egyptian Art NotesDocumento6 páginasCH3 Egyptian Art Notesmmcnamee9620100% (1)

- Paleolithic ArtDocumento35 páginasPaleolithic ArtJorge0% (1)

- Ancient Greek Art (Art Ebook)Documento188 páginasAncient Greek Art (Art Ebook)Jan Aykk100% (4)

- A Handbook of Greek Sculpture 1000002121Documento590 páginasA Handbook of Greek Sculpture 1000002121Marian Dragos50% (2)

- The Aegina Marbles Time To Come HomeDocumento6 páginasThe Aegina Marbles Time To Come HomeCerigoAinda não há avaliações

- Greek ArchitectureDocumento98 páginasGreek ArchitectureAnkush Rai100% (1)

- Greek Vase PaintingDocumento75 páginasGreek Vase PaintingDeniz Baş100% (10)

- Hellenistic AgeDocumento30 páginasHellenistic AgeCarolina TobarAinda não há avaliações

- Art of Ancient EgyptDocumento24 páginasArt of Ancient EgyptChidinma Glory EjikeAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient Egyptian ArtDocumento10 páginasAncient Egyptian ArtKeithlan Rosie Fetil LlanzaAinda não há avaliações

- Greek Art SlidesDocumento54 páginasGreek Art SlidesLKMs HUBAinda não há avaliações

- The Three Periods of Greek ArtDocumento9 páginasThe Three Periods of Greek ArtEdith DalidaAinda não há avaliações

- Greek Art This Period in Art History Took Place From About 800 B.C To 50 B.CDocumento23 páginasGreek Art This Period in Art History Took Place From About 800 B.C To 50 B.CBryan ManlapigAinda não há avaliações

- Greek Art This Period in Art History Took Place From About 800 B.C To 50 B.CDocumento23 páginasGreek Art This Period in Art History Took Place From About 800 B.C To 50 B.CBryan ManlapigAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture-The Ancient World IIDocumento36 páginasLecture-The Ancient World IILeila GhiassiAinda não há avaliações

- Greece Outline 2018-2019Documento4 páginasGreece Outline 2018-2019api-288056601Ainda não há avaliações

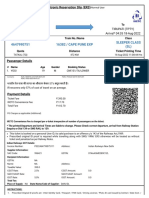

- Cape Pune Exp Sleeper Class (SL)Documento2 páginasCape Pune Exp Sleeper Class (SL)Yogiswar Goud RathipinniAinda não há avaliações

- Mediabase YearEnd 2010Documento35 páginasMediabase YearEnd 2010Miguel CortésAinda não há avaliações

- Deceitful CharactersDocumento2 páginasDeceitful Characterslauren_alves_2Ainda não há avaliações

- Vintage Airplane - Nov 1996Documento36 páginasVintage Airplane - Nov 1996Aviation/Space History LibraryAinda não há avaliações

- Tuskish Basics 12Documento115 páginasTuskish Basics 12Antonis HajiioannouAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson A: Lifestyle Trends: DecreasedDocumento3 páginasLesson A: Lifestyle Trends: DecreasedJean Pierre Sulluchuco ValentinAinda não há avaliações

- Recreation and LeisureDocumento42 páginasRecreation and LeisureGina del Mar75% (4)

- WH - Question Practice and Tense MixDocumento3 páginasWH - Question Practice and Tense MixAn LêAinda não há avaliações

- RRR Rabbit Care Info 2021Documento7 páginasRRR Rabbit Care Info 2021api-534158176Ainda não há avaliações

- Thirsty Sword Lesbians - Advanced Lovers Lesbians TablesDocumento14 páginasThirsty Sword Lesbians - Advanced Lovers Lesbians TablesJaceAinda não há avaliações

- WOL-3 - Dragons of SpringDocumento341 páginasWOL-3 - Dragons of SpringRyan Hall100% (15)

- The West Texas FrontierDocumento777 páginasThe West Texas FrontierDoug Williams100% (1)

- Session 2 - English ViDocumento20 páginasSession 2 - English ViMANUEL FELIPE HUERTAS PINGOAinda não há avaliações

- Complex SentencesDocumento3 páginasComplex SentencesPilar Romero CandauAinda não há avaliações

- 90 Day Bikini Home Workout Weeks 5 - 8Documento5 páginas90 Day Bikini Home Workout Weeks 5 - 8Breann EllingtonAinda não há avaliações

- How To Guide - Producing Nursery Rhyme Animations in 3DS MaxDocumento9 páginasHow To Guide - Producing Nursery Rhyme Animations in 3DS Maxapi-311443861Ainda não há avaliações

- Dokumen Tips Ethio Telecom Teleom Itiens Arter Etio Teleom ItiensDocumento22 páginasDokumen Tips Ethio Telecom Teleom Itiens Arter Etio Teleom ItiensYohannes LerraAinda não há avaliações

- The End of The Gpu Roadmap: Tim Sweeney CEO, Founder Epic GamesDocumento74 páginasThe End of The Gpu Roadmap: Tim Sweeney CEO, Founder Epic Gamesapi-26184004Ainda não há avaliações

- Resume 2Documento2 páginasResume 2api-699453949Ainda não há avaliações

- 6 Tourist Information Office PDFDocumento7 páginas6 Tourist Information Office PDFMaría Luján PorcelliAinda não há avaliações

- Defensive Depth ChartDocumento2 páginasDefensive Depth ChartAnonymous Q0S8eeAxoAinda não há avaliações

- 0471 w12 Ms 2 PDFDocumento9 páginas0471 w12 Ms 2 PDFMuhammad Talha Yousuf SyedAinda não há avaliações

- Marketing and Advertising Casino Dealer Program 2Documento3 páginasMarketing and Advertising Casino Dealer Program 2Angela BrownAinda não há avaliações

- PRINT - Service Manuals - Service Manual MC Kinley Eu GD 13 06 2019Documento73 páginasPRINT - Service Manuals - Service Manual MC Kinley Eu GD 13 06 2019Sebastian PettersAinda não há avaliações

- Kindergarten Boyfriend From HeathersDocumento11 páginasKindergarten Boyfriend From HeathersRaquel Carvalho100% (3)

- Revenge Is All The SweeterDocumento228 páginasRevenge Is All The Sweetererica babad100% (1)

- xlr8 Carb CyclingDocumento67 páginasxlr8 Carb CyclingH DrottsAinda não há avaliações

- (Ebook) Star Wars Encyclopedia Galactica Vol 2Documento68 páginas(Ebook) Star Wars Encyclopedia Galactica Vol 2gdq6280100% (2)

- Spare Parts List: Sludge Pumps CP 0077Documento16 páginasSpare Parts List: Sludge Pumps CP 0077obumuyaemesiAinda não há avaliações

- Kbeatbox KSNet450 User GuideDocumento12 páginasKbeatbox KSNet450 User GuideRin DragonAinda não há avaliações