Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

CH 09

Enviado por

Hemant KumarDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

CH 09

Enviado por

Hemant KumarDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

C H AP T E R

9

The Analysis

of Competitive

Markets

Prepared by:

Fernando & Yvonn

Quijano

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

CHAPTER 9 OUTLINE

9.1 Evaluating the Gains and Losses from

Government PoliciesConsumer and

Producer Surplus

9.2 The Efficiency of a Competitive Market

9.3 Minimum Prices

9.4 Price Supports and Production Quotas

9.5 Import Quotas and Tariffs

9.6 The Impact of a Tax or Subsidy

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

2 of 28

9.1

EVALUATING THE GAINS AND LOSSES

FROM GOVERNMENT POLICIES

CONSUMER AND PRODUCER SURPLUS

Review of Consumer and Producer Surplus

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

Figure 9.1

Consumer and Producer

Surplus

Consumer A would pay $10

for a good whose market

price is $5 and therefore

enjoys a benefit of $5.

Consumer B enjoys a benefit

of $2,

and Consumer C, who

values the good at exactly

the market price, enjoys no

benefit.

Consumer surplus, which

measures the total benefit to

all consumers, is the yellowshaded area between the

demand curve and the

market price.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

3 of 28

9.1

EVALUATING THE GAINS AND LOSSES

FROM GOVERNMENT POLICIES

CONSUMER AND PRODUCER SURPLUS

Review of Consumer and Producer Surplus

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

Figure 9.1

Consumer and Producer

Surplus (continued)

Producer surplus measures

the total profits of producers,

plus rents to factor inputs.

It is the benefit that lowercost producers enjoy by

selling at the market price,

shown by the green-shaded

area between the supply

curve and the market price.

Together, consumer and

producer surplus measure

the welfare benefit of a

competitive market.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

4 of 28

9.1

EVALUATING THE GAINS AND LOSSES

FROM GOVERNMENT POLICIES

CONSUMER AND PRODUCER SURPLUS

Application of Consumer and Producer Surplus

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

welfare effects

Figure 9.2

Change in Consumer and Producer

Surplus from Price Controls

Gains and losses to consumers and producers.

deadweight loss Net loss of

total (consumer plus producer)

surplus.

The price of a good has been

regulated to be no higher than

Pmax, which is below the

market-clearing price P0.

The gain to consumers is the

difference between rectangle A

and triangle B.

The loss to producers is the

sum of rectangle A and triangle

C.

Triangles B and C together

measure the deadweight loss

from price controls.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

5 of 28

9.1

EVALUATING THE GAINS AND LOSSES

FROM GOVERNMENT POLICIES

CONSUMER AND PRODUCER SURPLUS

Application of Consumer and Producer Surplus

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

Figure 9.3

Effect of Price Controls When

Demand Is Inelastic

If demand is sufficiently

inelastic, triangle B can be

larger than rectangle A. In this

case, consumers suffer a net

loss from price controls.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

6 of 28

9.1

EVALUATING THE GAINS AND LOSSES FROM GOVERNMENT POLICIES

CONSUMER AND PRODUCER SURPLUS

Supply: QS = 15.90 + 0.72PG + 0.05PO

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

Figure 9.4

Demand: QD = 10.35 0.18PG + 0.69PO

Effects of Natural Gas Price

Controls

The market-clearing price

of natural gas is $6.40

per mcf, and the

(hypothetical) maximum

allowable price is $3.00.

A shortage of 23.6 20.6

= 3.0 Tcf results.

The gain to consumers is

rectangle A minus

triangle B,

and the loss to producers

is rectangle A plus

triangle C.

The deadweight loss is

the sum of triangles B

plus C.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

7 of 28

9.2

THE EFFICIENCY OF A COMPETITIVE MARKET

economic efficiency Maximization of aggregate

consumer and producer surplus.

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

Market Failure

market failure Situation in which an unregulated

competitive market is inefficient because prices fail to

provide proper signals to consumers and producers.

There are two important instances in which market failure can occur:

1. Externalities

2. Lack of Information

externality Action taken by either a producer or a

consumer which affects other producers or consumers

but is not accounted for by the market price.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

8 of 28

9.2

THE EFFICIENCY OF A COMPETITIVE MARKET

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

Figure 9.5

Welfare Loss When Price is Held

Above Market-Clearing Level

When price is regulated to be

no lower than P2, only Q3 will

be demanded.

If Q3 is produced, the

deadweight loss is given by

triangles B and C.

At price P2, producers would

like to produce more than Q3.

If they do, the deadweight

loss will be even larger.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

9 of 28

9.2

THE EFFICIENCY OF A COMPETITIVE MARKET

Supply: QS = 16,000 + 0.4P

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

Figure 9.6

Demand: QD = 32,0000.4P

The Market for Kidneys and the

Effect of the National Organ

Transplantation Act

The market-clearing price is

$20,000; at this price, about

24,000 kidneys per year would

be supplied.

The law effectively makes the

price zero. About 16,000

kidneys per year are still

donated; this constrained

supply is shown as S.

The loss to suppliers is given

by rectangle A and triangle C.

If consumers received kidneys

at no cost, their gain would be

given by rectangle A less

triangle B.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

10 of 28

9.2

THE EFFICIENCY OF A COMPETITIVE MARKET

Supply: QS = 16,000 + 0.4P

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

Figure 9.6

Demand: QD = 32,0000.4P

The Market for Kidneys and the

Effect of the National Organ

Transplantation Act (continued)

In practice, kidneys are often

rationed on the basis of

willingness to pay, and many

recipients pay most or all of

the $40,000 price that clears

the market when supply is

constrained.

Rectangles A and D

measure the total value of

kidneys when supply is

constrained.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

11 of 28

9.3

MINIMUM PRICES

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

Figure 9.7

Price Minimum

Price is regulated to be no lower

than Pmin.

Producers would like to supply Q2,

but consumers will buy only Q3.

If producers indeed produce Q2,

the amount Q2 Q3 will go unsold

and the change in producer

surplus will be A C D. In this

case, producers as a group may

be worse off.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

12 of 28

9.3

MINIMUM PRICES

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

Figure 9.8

The Minimum Wage

Although the market-clearing

wage is w0,

firms are not allowed to pay less

than wmin.

This results in unemployment of

an amount L2 L1

and a deadweight loss given by

triangles B and C.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

13 of 28

9.3

MINIMUM PRICES

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

Figure 9.9

Effect of Airline Regulation by

the Civil Aeronautics Board

At price Pmin, airlines would

like to supply Q2, well above

the quantity Q1 that

consumers will buy.

Here they supply Q3.

Trapezoid D is the cost of

unsold output.

Airline profits may have

been lower as a result of

regulation because triangle

C and trapezoid D can

together exceed rectangle

A.

In addition, consumers lose

A + B.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

14 of 28

9.3

MINIMUM PRICES

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

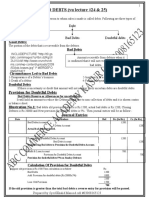

TABLE 9.1 Airline Industry Data

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

Number of Carriers

36

63

102

70

Passenger Load Factor

54

58

61

Passenger Mile Rate

(Constant 1995 dollars)

.218

.210

Real Cost Index (1995 = 100)

101

Real Fuel Cost Index (1995

= 100)

Real Cost Index Corrected for

Fuel Cost Changes

2000

2005

96

94

90

62

67

72

78

.165

.150

.129

.118

.092

122

111

109

100

101

93

249

300

204

163

100

125

237

71

73

88

95

100

96

67

By 1981, the airline industry had been completely deregulated. Since that time, many

new airlines have begun service, others have gone out of business, and price

competition has become much more intense. Because airlines have no control over

oil prices, it is more informative to examine a corrected real cost index which

removes the effects of changing fuel costs.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

15 of 28

9.4

PRICE SUPPORTS AND PRODUCTION QUOTAS

Price Supports

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

price support Price set by government above free

market level and maintained by governmental purchases

of excess supply.

Figure 9.10

Prince Supports

To maintain a price Ps above the

market-clearing price P0, the

government buys a quantity Qg.

The gain to producers is A + B +

D. The loss to consumers is A +

B.

The cost to the government is the

speckled rectangle, the area of

which is Ps(Q2 Q1).

Total change in welfare: CS + PS Cost to Govt. = D (Q2 Q1)Ps

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

16 of 28

9.4

PRICE SUPPORTS AND PRODUCTION QUOTAS

Production Quotas

Figure 9.11

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

Supply Restrictions

To maintain a price Ps above the

market-clearing price P0, the

government can restrict supply to

Q1, either by imposing production

quotas (as with taxicab medallions)

or by giving producers a financial

incentive to reduce output (as with

acreage limitations in agriculture).

For an incentive to work, it must be

at least as large as B + C + D,

which would be the additional profit

earned by planting, given the higher

price Ps. The cost to the

government is therefore at least B +

C + D.

CS = A B

PS = A C + Payments for not producing (or at least B + C + D)

Welfare = A B + A + B + D B C D = B C

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

17 of 28

9.4

PRICE SUPPORTS AND PRODUCTION QUOTAS

Figure 9.12

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

The Wheat Market in 1981

1981 Supply: QS = 1800 + 240P

1981 Demand: QD = 3550 266P

To increase the price to

$3.70, the government

must buy a quantity of

wheat Qg.

By buying 122 million

bushels of wheat, the

government increased

the market-clearing

price from $3.46 per

bushel to $3.70.

1981 Total demand: QDT = 3550 266P + Qg

Qg= 506P 1750

Qg= (506)(3.70) 1750 = 122 million bushels

Loss to consumers = A B = $624 million

Cost to the government = $3.70 x 112 million = $451.4 million

Total cost of the program = $624 million + $451.4 million = $1075.4 million

Gain to producers = A + B + C = $638 million

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

18 of 28

9.4

PRICE SUPPORTS AND PRODUCTION QUOTAS

Figure 9.13

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

The Wheat Market in 1985

1985 Supply: QS = 1800 + 240P

1985 Demand: QD = 2580 194P

In 1985, the demand for

wheat was much lower

than in 1981, because

the market-clearing

price was only $1.80.

To increase the price to

$3.20, the government

bought 466 million

bushels and also

imposed a production

quota of 2425 million

bushels.

2425 = 2580 194P + Qg

Qg= 155 + 194P

Qg= 155 + 194($3.20) = 466 million bushels

Cost to the government = $3.20 x 466 million = $1491 million

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

19 of 28

9.5

IMPORT QUOTAS AND TARIFFS

import quota

imported.

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

tariff

Limit on the quantity of a good that can be

Tax on an imported good.

Figure 9.14

Import Tariff or Quota That

Eliminates Imports

In a free market, the domestic

price equals the world price Pw.

A total Qd is consumed, of which

Qs is supplied domestically and

the rest imported.

When imports are eliminated,

the price is increased to P0.

The gain to producers is

trapezoid A.

The loss to consumers is A + B

+ C, so the deadweight loss is B

+ C.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

20 of 28

9.5

IMPORT QUOTAS AND TARIFFS

Figure 9.15

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

Import Tariff or Quota (General Case)

When imports are reduced, the

domestic price is increased

from Pw to P*.

This can be achieved by a

quota, or by a tariff T = P* Pw.

Trapezoid A is again the gain to

domestic producers.

The loss to consumers is A + B

+ C + D.

If a tariff is used, the

government gains D, the

revenue from the tariff. The net

domestic loss is B + C.

If a quota is used instead,

rectangle D becomes part of the

profits of foreign producers, and

the net domestic loss is B + C +

D.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

21 of 28

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

9.5

IMPORT QUOTAS AND TARIFFS

Figure 9.16

U.S. supply: QS = 7.48 + 0.84P

Sugar Quota in 2005

U.S. demand: QD = 26.7 0.23P

At the world price of 12

cents per pound, about

23.9 billion pounds of

sugar would have been

consumed in the United

States in 2005, of which all

but 2.6 billion pounds

would have been imported.

Restricting imports to 5.3

billion pounds caused the

U.S. price to go up by 15

cents.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

22 of 28

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

9.5

IMPORT QUOTAS AND TARIFFS

Figure 9.16

U.S. supply: QS = 7.48 + 0.84P

Sugar Quota in 2005 (continued)

U.S. demand: QD = 26.7 0.23P

The gain to domestic

producers was trapezoid A,

about $1.3 billion.

Rectangle D, $795 million,

was a gain to those foreign

producers who obtained

quota allotments.

Triangles B and C

represent the deadweight

loss of about $1.2 billion.

The cost to consumers, A

+ B + C + D, was about

$3.3 billion.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

23 of 28

9.6

THE IMPACT OF A TAX OR SUBSIDY

specific tax

Tax of a certain amount of money per unit sold.

Figure 9.17

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

Incidence of a Tax

Pb is the price (including the

tax) paid by buyers. Ps is the

price that sellers receive, less

the tax.

Here the burden of the tax is

split evenly between buyers

and sellers.

Buyers lose A + B.

Sellers lose D + C.

The government earns A + D

in revenue.

The deadweight loss is B + C.

Market clearing requires four conditions to be satisfied after the tax is in place:

QD = QD(Pb)

(9.1a)

QS = QS(Ps)

(9.1b)

QD = QS

Pb Ps = t

(9.1c)

(9.1d)

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

24 of 28

9.6

THE IMPACT OF A TAX OR SUBSIDY

Figure 9.18

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

Impact of a Tax Depends on Elasticities of Supply and Demand

If demand is very inelastic relative to

supply, the burden of the tax falls

mostly on buyers.

If demand is very elastic relative to

supply, it falls mostly on sellers.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

25 of 28

9.6

THE IMPACT OF A TAX OR SUBSIDY

The Effects of a Subsidy

subsidy Payment reducing the buyers price below the

sellers price; i.e., a negative tax.

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

Conditions needed for the market to clear with a subsidy:

Figure 9.19

QD = QD(Pb)

(9.2a)

QS = QS(Ps)

(9.2b)

QD = QS

Ps Pb = s

(9.2c)

(9.2d)

Subsidy

A subsidy can be thought of

as a negative tax. Like a

tax, the benefit of a subsidy

is split between buyers and

sellers, depending on the

relative elasticities of supply

and demand.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

26 of 28

9.6

THE IMPACT OF A TAX OR SUBSIDY

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

Effect of a $1.00-per-gallon tax:

QD = 150 25Pb

(Demand)

QS = 60 + 20Ps

(Supply)

QD = Q S

Pb Ps = 1.00

(Supply must equal demand)

(Government must receive $1.00/gallon)

150 25Pb = 60 + 20Ps

Pb = Ps + 1.00

150 25Pb = 60 + 20Ps

20Ps + 25Ps = 150 25 60

45Ps = 65, or Ps = 1.44

Q = 150 (25)(2.44) = 150 61, or Q = 89 bg/yr

Annual revenue from the tax tQ = (1.00)(89) = $89 billion per year

Deadweight loss: (1/2) x ($1.00/gallon) x (11 billion gallons/year = $5.5 billion

per year

27 of 28

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

9.6

THE IMPACT OF A TAX OR SUBSIDY

Gasoline demand: QD = 150 25P

Figure 9.20

Gasoline supply: QS = 60 + 20P

Chapter 9: The Analysis of Competitive Markets

Impact of $1 Gasoline Tax

The price of gasoline at

the pump increases

from $2.00 per gallon to

$2.44, and the quantity

sold falls from 100 to 89

bg/yr.

Annual revenue from

the tax is (1.00)(89) =

$89 billion (areas A +

D).

The two triangles show

the deadweight loss of

$5.5 billion per year.

Copyright 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall Microeconomics Pindyck/Rubinfeld, 7e.

28 of 28

Você também pode gostar

- Problem Set 1Documento2 páginasProblem Set 1Cooper Greenfield0% (1)

- Operations and Materials ManagementDocumento6 páginasOperations and Materials Managementakamalapuri3880% (2)

- Corporate Finance SyllabusDocumento2 páginasCorporate Finance SyllabusaAinda não há avaliações

- Microeconomics: by Robert S. Pindyck Daniel Rubinfeld Ninth EditionDocumento35 páginasMicroeconomics: by Robert S. Pindyck Daniel Rubinfeld Ninth EditionRais Mitra Mahardika0% (1)

- Mid-Term Exam (With Answers)Documento12 páginasMid-Term Exam (With Answers)Wallace HungAinda não há avaliações

- Ch02 PindyckDocumento71 páginasCh02 Pindyckpjs_canAinda não há avaliações

- Discussion Questions For Global Aircraft ManufacturingDocumento1 páginaDiscussion Questions For Global Aircraft ManufacturingDeepankur Malik0% (3)

- Microeconomics Hubbard CH 11 AnswersDocumento10 páginasMicroeconomics Hubbard CH 11 AnswersLeah LeeAinda não há avaliações

- Solutions to Moodle Quiz 1 (MicroeconomicsDocumento8 páginasSolutions to Moodle Quiz 1 (MicroeconomicsneomilanAinda não há avaliações

- An Operational Application of System Dynamics in The Automotive Industry: Inventory Management at BMWDocumento10 páginasAn Operational Application of System Dynamics in The Automotive Industry: Inventory Management at BMWGourav DebAinda não há avaliações

- ch03 08 31 08Documento37 páginasch03 08 31 08Hemant KumarAinda não há avaliações

- JHSB IM: Poultry Industry Outlook and Marketing StrategyDocumento54 páginasJHSB IM: Poultry Industry Outlook and Marketing StrategyNick Hamasholdin AhmadAinda não há avaliações

- Externalities and Public Goods: Prepared byDocumento35 páginasExternalities and Public Goods: Prepared byAnik RoyAinda não há avaliações

- Markets For Factor Inputs: Prepared byDocumento29 páginasMarkets For Factor Inputs: Prepared byrameshaarya99Ainda não há avaliações

- Chapter 8Documento14 páginasChapter 8Patricia AyalaAinda não há avaliações

- Analysis of Competitive MarketsDocumento22 páginasAnalysis of Competitive Marketswmmcgregor93Ainda não há avaliações

- Profit Maximization and Competitive Supply: Chapter OutlineDocumento14 páginasProfit Maximization and Competitive Supply: Chapter Outlinevarun kumar VermaAinda não há avaliações

- Market Power: Monopoly: Chapter OutlineDocumento12 páginasMarket Power: Monopoly: Chapter OutlineNur Suraya Alias100% (1)

- CH 07Documento50 páginasCH 07Prerna MittalAinda não há avaliações

- CH 06Documento24 páginasCH 06rameshaarya99100% (1)

- Game Theory and Competitive StrategyDocumento119 páginasGame Theory and Competitive StrategyPhuong TaAinda não há avaliações

- PindyckRubinfeld Microeconomics Ch10Documento50 páginasPindyckRubinfeld Microeconomics Ch10Wisnu Fajar Baskoro50% (2)

- Measuring A Nation'S Income: Questions For ReviewDocumento4 páginasMeasuring A Nation'S Income: Questions For ReviewNoman MustafaAinda não há avaliações

- Homework MicroeconomicsDocumento4 páginasHomework MicroeconomicsNguyễn Bảo Ngọc100% (1)

- Mankiw Taylor PPT002Documento36 páginasMankiw Taylor PPT002Jan KranenkampAinda não há avaliações

- Department of Economics: Bharathiar UniversityDocumento44 páginasDepartment of Economics: Bharathiar UniversityPratyusha Khandelwal0% (1)

- ch05 08 31 08Documento34 páginasch05 08 31 08anon_946247999Ainda não há avaliações

- Production Function: Short-Run and Long-Run Production TheoryDocumento13 páginasProduction Function: Short-Run and Long-Run Production TheorygunjannisarAinda não há avaliações

- 10e 12 Chap Student WorkbookDocumento23 páginas10e 12 Chap Student WorkbookkartikartikaaAinda não há avaliações

- CH 11 Pricing StrategyDocumento43 páginasCH 11 Pricing StrategytunggaltriAinda não há avaliações

- Dissertation Oligopoly and ApplicationDocumento56 páginasDissertation Oligopoly and ApplicationPham ThảoAinda não há avaliações

- Managerial Economics:: Perfect CompetitionDocumento43 páginasManagerial Economics:: Perfect CompetitionPhong VũAinda não há avaliações

- T2-Macroeconomics Course Outline 2020-21Documento6 páginasT2-Macroeconomics Course Outline 2020-21Rohit PanditAinda não há avaliações

- Pindyck PPT CH02Documento50 páginasPindyck PPT CH02Muthia KhairaniAinda não há avaliações

- Profits and Perfect Competition: (Unit VI.i Problem Set Answers)Documento12 páginasProfits and Perfect Competition: (Unit VI.i Problem Set Answers)nguyen tuanhAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 1 - Inventory Models - Part 1Documento30 páginasChapter 1 - Inventory Models - Part 1Binyam KebedeAinda não há avaliações

- CH 09Documento10 páginasCH 09leisurelarry999Ainda não há avaliações

- Managerial Economics:: Demand TheoryDocumento68 páginasManagerial Economics:: Demand TheoryPhong VũAinda não há avaliações

- Sample Exam 3Documento8 páginasSample Exam 3Luu Nguyen Quyet ThangAinda não há avaliações

- SOLVERDocumento55 páginasSOLVERRichárd FráterAinda não há avaliações

- Estimating Demand Functions: Managerial EconomicsDocumento38 páginasEstimating Demand Functions: Managerial EconomicsalauoniAinda não há avaliações

- 10e 08 Chap Student Workbook PDFDocumento20 páginas10e 08 Chap Student Workbook PDFPRAGYAN PANDAAinda não há avaliações

- 4 Efficiency, Price Controls & TaxesDocumento15 páginas4 Efficiency, Price Controls & Taxesdeeptitripathi09Ainda não há avaliações

- Micro Quiz 5Documento7 páginasMicro Quiz 5Mosh100% (1)

- Chapter 3 (National Income - Where It Comes From and Where It Goes)Documento16 páginasChapter 3 (National Income - Where It Comes From and Where It Goes)Khadeeza ShammeeAinda não há avaliações

- CH 16 CheckpointDocumento57 páginasCH 16 CheckpointVũ Hồng HạnhAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 9 Micro-Economics ReviewDocumento55 páginasChapter 9 Micro-Economics ReviewMeg GregoireAinda não há avaliações

- PPC QuestionsDocumento4 páginasPPC Questionssumedhasajeewani100% (1)

- MICROECONOMICS ExercisesDocumento2 páginasMICROECONOMICS ExercisesAdrian CorredorAinda não há avaliações

- Final Exam 100A SolutionsDocumento16 páginasFinal Exam 100A SolutionsJessie KongAinda não há avaliações

- Documento13 PDFDocumento31 páginasDocumento13 PDFNico TuscaniAinda não há avaliações

- Eco McqsDocumento13 páginasEco McqsUn Konown Do'erAinda não há avaliações

- S4 (01) Basic Concepts.Documento7 páginasS4 (01) Basic Concepts.Cheuk Wai LauAinda não há avaliações

- Lab #2 Chapter 2 - The Economic ProblemDocumento14 páginasLab #2 Chapter 2 - The Economic ProblemLucasStarkAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter12 SlidesDocumento15 páginasChapter12 SlidesParth Rajesh ShethAinda não há avaliações

- Tutorial QuestionsDocumento66 páginasTutorial QuestionsKim Chi100% (1)

- The Cost of Production: Prepared byDocumento50 páginasThe Cost of Production: Prepared byRoni Anom SatrioAinda não há avaliações

- CH 09Documento28 páginasCH 09rameshaarya99Ainda não há avaliações

- The Analysis of Competitive Markets: Prepared byDocumento28 páginasThe Analysis of Competitive Markets: Prepared byLukman AguilarAinda não há avaliações

- The Analysis of Competitive Markets: Prepared byDocumento7 páginasThe Analysis of Competitive Markets: Prepared byLukman AguilarAinda não há avaliações

- Micro EconomicsDocumento36 páginasMicro EconomicsTashianna ColeyAinda não há avaliações

- Pr8e Ge Ch09Documento30 páginasPr8e Ge Ch09Sup AkiAinda não há avaliações

- Summarised Information Under RTI For IPM 2016Documento1 páginaSummarised Information Under RTI For IPM 2016Hemant KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Hall Ticket ExamDocumento1 páginaHall Ticket ExamHemant KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Business Report Notebook KitDocumento7 páginasBusiness Report Notebook KitHemant KumarAinda não há avaliações

- IPM BrochureDocumento8 páginasIPM BrochureAmartya MitraAinda não há avaliações

- ch06 08 31 08Documento24 páginasch06 08 31 08Hemant KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Sensitivity Analysis and Dual Prices in Linear ProgrammingDocumento12 páginasSensitivity Analysis and Dual Prices in Linear ProgrammingHemant KumarAinda não há avaliações

- OB II Sessions 11-14 HandoutDocumento9 páginasOB II Sessions 11-14 HandoutHemant KumarAinda não há avaliações

- RedBus Ticket TK3B46335554Documento2 páginasRedBus Ticket TK3B46335554Hemant KumarAinda não há avaliações

- SKRastogi - Teaching Note - Lancaster Consumption TechnologyDocumento6 páginasSKRastogi - Teaching Note - Lancaster Consumption TechnologyHemant KumarAinda não há avaliações

- 311 Session3Documento39 páginas311 Session3venkeeeeeAinda não há avaliações

- CA13Documento294 páginasCA13Knowitall77Ainda não há avaliações

- What is Psychology? An Introduction to the Major Subfields and Theoretical PerspectivesDocumento29 páginasWhat is Psychology? An Introduction to the Major Subfields and Theoretical PerspectivesHemant Kumar100% (2)

- IIM INDORE OVER THE YEARS: A CHRONICLE OF ACHIEVEMENTSDocumento0 páginaIIM INDORE OVER THE YEARS: A CHRONICLE OF ACHIEVEMENTSHemant KumarAinda não há avaliações

- CRISIL Audited Report - PGP - Finals - 2013Documento18 páginasCRISIL Audited Report - PGP - Finals - 2013Hemant KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Measuring Brand EquityDocumento38 páginasMeasuring Brand Equityjai1965Ainda não há avaliações

- Book 1 Chapter 2Documento4 páginasBook 1 Chapter 2Tanveer AhmadAinda não há avaliações

- Vocabulary Power Through Shakespeare: David PopkinDocumento19 páginasVocabulary Power Through Shakespeare: David PopkinimamjabarAinda não há avaliações

- LNS 2018 1 2016Documento26 páginasLNS 2018 1 2016Aini RoslieAinda não há avaliações

- MGT 101 SampleDocumento9 páginasMGT 101 SampleWaleed AbbasiAinda não há avaliações

- Ac 518 Hand-Outs Government Accounting and Auditing TNCR: The National Government of The PhilippinesDocumento53 páginasAc 518 Hand-Outs Government Accounting and Auditing TNCR: The National Government of The PhilippinesHarley Gumapon100% (1)

- Cost-Volume-Profit Relationships: Management Accountant 1 and 2Documento85 páginasCost-Volume-Profit Relationships: Management Accountant 1 and 2Bianca IyiyiAinda não há avaliações

- Mba Interview QuestionsDocumento3 páginasMba Interview QuestionsAxis BankAinda não há avaliações

- 1240 - Dela Cruz v. ConcepcionDocumento6 páginas1240 - Dela Cruz v. ConcepcionRica Andrea OrtizoAinda não há avaliações

- Presentation On The Topic of Theory of Journal, Trial and LedgerDocumento20 páginasPresentation On The Topic of Theory of Journal, Trial and LedgerharshitaAinda não há avaliações

- Sample Question AnswerDocumento57 páginasSample Question Answerসজীব বসুAinda não há avaliações

- Rural DevelopmentDocumento55 páginasRural DevelopmentmeenatchiAinda não há avaliações

- Preparing Financial StatementsDocumento6 páginasPreparing Financial StatementsAUDITOR97Ainda não há avaliações

- Playing To Win: in The Business of SportsDocumento8 páginasPlaying To Win: in The Business of SportsAshutosh JainAinda não há avaliações

- New Challenges For Wind EnergyDocumento30 páginasNew Challenges For Wind EnergyFawad Ali KhanAinda não há avaliações

- E3 - Revenue RCM TemplateDocumento51 páginasE3 - Revenue RCM Templatenazriya nasarAinda não há avaliações

- Financial Analysis On Scooters India LimitedDocumento9 páginasFinancial Analysis On Scooters India LimitedMohit KanjwaniAinda não há avaliações

- Wa0022.Documento37 páginasWa0022.karishmarakhi03Ainda não há avaliações

- Calculating Transaction Price for New ProductDocumento3 páginasCalculating Transaction Price for New Productjefferson sarmientoAinda não há avaliações

- Learning The LegaleseDocumento30 páginasLearning The LegaleseapachedaltonAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 13-A Regular Allowable Itemized DeductionsDocumento13 páginasChapter 13-A Regular Allowable Itemized DeductionsGeriel FajardoAinda não há avaliações

- Accounting & Control: Cost ManagementDocumento21 páginasAccounting & Control: Cost ManagementAgus WijayaAinda não há avaliações

- Microfinance Challenges and Opportunities in PakistanDocumento10 páginasMicrofinance Challenges and Opportunities in PakistanAmna NasserAinda não há avaliações

- Government of Ghana MLGRD A Operational Manual For Dpat 2016 A 1st CycleDocumento84 páginasGovernment of Ghana MLGRD A Operational Manual For Dpat 2016 A 1st CycleGifty BaidooAinda não há avaliações

- Clarifies On News Item (Company Update)Documento3 páginasClarifies On News Item (Company Update)Shyam SunderAinda não há avaliações

- Welcome To India's No. 1 Mobile Phone Repair & Refurb CenterDocumento18 páginasWelcome To India's No. 1 Mobile Phone Repair & Refurb CenterYaantra IndiaAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Pfrs 9Documento36 páginasIntroduction To Pfrs 9Natalie SerranoAinda não há avaliações

- Foreign Capital and ForeignDocumento11 páginasForeign Capital and Foreignalu_tAinda não há avaliações

- Excel Solutions - CasesDocumento25 páginasExcel Solutions - CasesJerry Ramos CasanaAinda não há avaliações

- Installment Payment AgreementDocumento1 páginaInstallment Payment AgreementBaisy VillanozaAinda não há avaliações