Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Jurding THT Elva Handy

Enviado por

Handhy Tanara0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

7 visualizações32 páginasfwvsdsa

Título original

Ppt Jurding THT Elva Handy

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PPTX, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentofwvsdsa

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PPTX, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

7 visualizações32 páginasJurding THT Elva Handy

Enviado por

Handhy Tanarafwvsdsa

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PPTX, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 32

JOURNAL READING

“Medical Management of Chronic Rhinosinusitis in Adults”

Pembimbing : dr. Khairan Irmansyah, Sp. THT-KL, M.Kes

ELVA OKTIANA RAHMI

HANDHY TANARA

1

Abstract

“ Chronic rhinosinusitis can be refractory and has

detrimental effects not only on symptoms, but

also on work absences, work productivity,

annual productivity costs, and disease-specific

quality of life measures.

There is evidence that it is driven by various

inflammatory pathways and host factors and is not

merely an infectious problem, although pathogens,

”

including bacterial biofilms, may certainly contribute to

this inflammatory cascade and to treatment resistance.

Given this, medical management should be

tailored to the specific comorbidities and problems in

an individual patient.

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic rhinosinusitis affects all races to a significant extent.

Prevalence within the United States in one study was 13.8% in

African Americans, 13% in Caucasians, 8.8% in Hispanics, and 7%

in Asians

This emphasizes that chronic rhinosinusitis has a significant impact

on all ethnicities and has a large economic impact. This highlights

the importance of effective treatment.

2. Definition and Classification

Rhinosinusitis is defined as inflammation of the

paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity that causes

symptoms.

It may be classified as:

• Acute rhinosinusitis (ARS) when it lasts less than four

weeks’ duration

• Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) when it lasts more than

12 weeks. During this time, patients may have acute

exacerbations, superimposed on their chronic

rhinosinusitis.

Rhinosinusitis may be caused by viruses, bacteria,

fungi, and noninfectious causes.

3. Diagnosis and Assessment

Clinicians should assess for:

• Nasal obstruction

• facial pain/pressure/fullness

• purulent nasal discharge

• and hyposmia, with two or more symptoms for greater than 12

weeks being highly sensitive for CRS.

These symptoms are also nonspecific, it is also recommended

that patients have objective evidence of sinonasal inflammation,

which can be visualized during:

anterior rhinoscopy

nasal endoscopy

or on computed tomography.

Inflammation is documented when one visualizes:

• Purulent rhinorrhea or edema in the middle meatus or

anterior ethmoid region

• Polyps in the nasal cavity or middle meatus

• and/or radiographic findings of inflammation.

These findings and the patient’s symptoms should be

persistent for greater than 12 weeks despite adequate

treatment for ARS, in order to diagnose CRS.

In addition, clinicians should assess for other factors that may

affect treatment in CRS:

• the presence or absence of nasal polyps

• asthma

• cystic fibrosis

• ciliary dyskinesia

• and an immunocompromised state.

• One may also consider obtaining testing for allergy and

immune function

4. Treatment

4.1. Acute Exacerbations of CRS and Biofilms

It is widely accepted that acute exacerbations of CRS

should be treated with oral antibiotics and this is

recommended by American, European, and Canadian

guidelines/position papers.

It is well accepted that bacteria trigger ARS and there has

been concern that inadequately treated ARS could cause

CRS.

patients may have comorbidities affecting these patients’

symptoms that were not identified (i.e., allergies)

There is some evidence that bacterial biofilms and

bacteria within epithelial cells contribute to inflammatory

cascades

Biofilms including Streptococcus pneumonia, Haemophilus

influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, S. aureus, and Pseudomonas

aeruginosa have been commonly identified in CRS patients both with

and without nasal polyps.

In addition, patients with biofilms have more severe preoperative

sinus disease, persistence of postoperative symptoms after sinus

surgery, ongoing mucosal inflammation, and infections.

In general, empiric oral antibiotics are used to treat acute

exacerbations.

Empiric antibiotic coverage targets common bacteria found in

CRS: S. pneumonia, H. influenzae, M. catarrhalis, S. aureus, P.

aeruginosa, and anaerobes.

some effective options include:

amoxicillin-clavulanate

second or third generation cephalosporin

respiratory fluoroquinolones

4.2. Chronic Rhinosinusitis (CRS) with Nasal Polyps

There is a lot of evidence emerging that S. aureus is implicated in at

least a subset of patients with CRS with nasal polyps, because

colonizing staphylococcal bacteria are producing superantigenic

toxins (Sags) that increase eosinophilic inflammation and promote

the formation of nasal polyps.

Total eosinophil counts correlated with the presence of nasal polyps,

asthma, and aspirin intolerance

When nasal polyps are present in CRS, patients should be

treated with intranasal therapy, including topical

intranasal steroids and/or saline nasal irrigation for

symptomatic relief.

in addition to long-term management of the nasal polyps

themselves with intranasal glucocorticoids which

decrease polyp size, polyp recurrence, decrease nasal

symptoms, and improve nasal airflow.

Topical intranasal corticosteroids are more effective when

administered with correct technique.

Oral corticosteroids are effective in decreasing polyp size

and nasal symptoms in the short term, but this must be

balanced with the risks of oral corticosteroids. It may be

useful for planned short-term improvement.

Long-term oral macrolides may be beneficial because of

their anti-inflammatory effects.

Intranasal saline irrigation should be used, as opposed to

intranasal saline spray because of increased

effectiveness on symptom relief and improving quality of

life.

Endoscopic sinus surgery is safe and effective in patients

with CRS with nasal polyps and is typically recommended

when patients’ signs and symptoms are refractory to

medical therapy.

endoscopic sinus surgery was shown to have equivalent

efficacy to medical management

4.3. Chronic Rhinosinusitis without Nasal Polyps

Intranasal steroids and/or nasal saline irrigation have been

shown to be beneficial in CRS without nasal polyps with

improved symptom scores.

Additions to nasal saline irrigation that have shown benefit

include sodium hypochlorite 0.05% in patients with S. aureus,

this is also felt to have possible effects on P. aeruginosa

Using xylitol in water as a sinonasal irrigation improved

symptom control compared to saline irrigation and can

potentially be a useful adjunctive treatment

There is inadequate data to promote the use of oral steroids in

CRS without nasal polyps .

Topical antibiotics do not show benefit in CRS without nasal

polyps.

Long-term antibiotics, primarily macrolides (azithromycin 500 g

weekly or roxithromycin 150 g daily), have shown possible

therapeutic response after treatment for 12 weeks.

Endoscopic sinus surgery in CRS without nasal polyps has been

shown to be safe and effective when medical treatment has

failed

4.4. Allergy

Allergic rhinitis is present in 40%–84% of patients with CRS.

allergic rhinitis is a superimposed exacerbating factor of CRS.

Patients with allergies and CRS are also more symptomatic

than those that have CRS without allergic rhinitis, despite

similar CT findings.

Intranasal glucocorticoids and/or nasal irrigation can be

beneficial.

4.5. Asthma and Aspirin Sensitivity

There is a high prevalence of CRS in patients with asthma and

they have found that asthma severity directly correlates with

the severity of sinus disease on imaging.

When CRS is treated (medically or surgically), asthma

symptoms improve and the need for asthma medications

decreases

In aspirin-tolerant patients with asthma or allergic rhinitis,

leukotriene inhibitors that antagonize CYSLTR1 can be

potentially beneficial (montelukast and zafirlukast)

There has been a study that combined treatment with

intranasal fluticasone and montelukast correlated with

improvement of nasal polyp size and CT findings, in

addition to others that demonstrate montelukast is better

than placebo in CRS with nasal polyps.

In aspirin sensitive patients, aspirin avoidance is an

important part of the management plan. One may also

consider aspirin desensitization

4.6. Cystic Fibrosis (CF)

CRS is reported in 30 to 67% of patients with CF (within all

age groups)

Some studies have suggested that this may be because

of genetic mutation.

It is clearer that similar bacteria occupy the upper and

lower airways of these CF patients, suggesting a

possible spread from the upper to lower airways

Inflammatory pathways may be treatment targets, in addition to

gene therapy and treatment of their microbiology.

More aggressive combined medical and surgical treatment

demonstrates improved control of CRS in CF patients.

A mucolytic, dornase alfa, once daily (2.5 mg)

administered intranasally either one month after

endoscopic sinus surgery, or without surgery

has been found to be improve compared to hypotonic

saline or normal saline.

It is also used for lower airway disease in these patients, but

with different dosing regimens and administration route (oral

inhalation).

topical antimicrobials show that they should not be first-

line therapies in CF patients for CRS.

There was a case report of successful use of ivacaftor in

refractory CRS related CF gene defect. Ivacaftor, a CF

transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)

potentiator, targets the G55ID-CFTR mutation in CF.

patients with CF that have endoscopic sinus surgery with

serial antimicrobial lavage had better outcomes than

surgery alone

4.7. Ciliary Dyskinesia

Decreased mucociliary clearance from ciliary dyskinesia

impacts a small percentage of patients with CRS (aside from

CF). Mucociliary transit time (MTT) is prolonged when patients

have underlying genetic-related ciliary dyskinesia

Effective treatments need to be further elucidated.

4.8. Immunodeficiency

Treatment with intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) and/or

prophylactic antibiotics is indicated in those with

immunoglobulin deficiency, which can improve survival

and decrease life-threatening infections.

However, it does not appear to affect radiologic

appearance of CRS and it is unclear that this clinically

improves CRS. Those with immunosuppression from HIV

infection should be treated for HIV to raise their CD4 count.

4.9. Fungal

Fungi have been found to be prevalent in patients with CRS

and local nasal tissue samples exhibit increased eosinophils,

but without increased IgE to indicate a mold allergy.

It is recommended not to use oral or topical antifungals given

greater risk of harm over potential benefit, in addition to their

high cost.

One area that remains less clear is allergic fungal

rhinosinusitis which appears to be a clinically distinct entity. It

demonstrates a Th2 immune response and also has specific

IgE in eosinophilic mucin and mucosa.

Treatment impact of this needs to be further elucidated.

Surgery with and without concomitant medical

management has been beneficial in allergic fungal

rhinosinusitis

CONCLUSIONS

• Chronic rhinosinusitis presents with uniform signs and

symptoms, but should be medically managed

according to the medical comorbidities and clinical

features present in an individual patient.

“I believe that the greatest gift you can

give your family and the world is a healthy

you”

- Joyce Meyer

THANKYOU

Você também pode gostar

- Delusional Disorder MedscapeDocumento14 páginasDelusional Disorder MedscapeHandhy Tanara100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

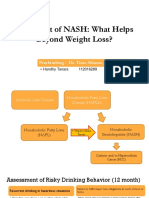

- Jurnal NashDocumento17 páginasJurnal NashHandhy TanaraAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Physiology of Bleeding To DeathDocumento2 páginasThe Physiology of Bleeding To DeathHandhy TanaraAinda não há avaliações

- Pertanyaan IleusDocumento1 páginaPertanyaan IleusHandhy TanaraAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Jurnal Reading: Treatment of NASH: What Helps Beyond Weight Loss?Documento1 páginaJurnal Reading: Treatment of NASH: What Helps Beyond Weight Loss?Handhy TanaraAinda não há avaliações

- Sharoon Covid TestDocumento3 páginasSharoon Covid TestVande GuruParamparaAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- NICU Manual Cheat SheetDocumento2 páginasNICU Manual Cheat Sheetlori_quintal92% (13)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Ocular Allergy Esen Karamursel Akpek, MDDocumento8 páginasOcular Allergy Esen Karamursel Akpek, MDAndri SaputraAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Etiology - The Etiology of Psoriasis Is ADocumento2 páginasEtiology - The Etiology of Psoriasis Is AJake DukesAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Vaccine Rejection and HesitancyDocumento7 páginasVaccine Rejection and HesitancyAlexander FrischAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- CHECKLIST PROCEDURES (Immunization)Documento2 páginasCHECKLIST PROCEDURES (Immunization)Elaine Frances IlloAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Elecsys Hbsag Ii: A) Tris (2,2'-Bipyridyl) Ruthenium (Ii) - Complex (Ru (Bpy) )Documento5 páginasElecsys Hbsag Ii: A) Tris (2,2'-Bipyridyl) Ruthenium (Ii) - Complex (Ru (Bpy) )Brian SamanyaAinda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Concept Mapping: Hodgskin'S Disease ComplicationDocumento4 páginasConcept Mapping: Hodgskin'S Disease ComplicationAsterlyn ConiendoAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Viral Hepatitis: Acute Inflamation of The Liver Caused by Primarly Hepatotropic Viruses (A, B, C, D, E)Documento35 páginasAcute Viral Hepatitis: Acute Inflamation of The Liver Caused by Primarly Hepatotropic Viruses (A, B, C, D, E)Tarik PlojovicAinda não há avaliações

- Nuñal Group - THYPHOID FEVER DraftDocumento5 páginasNuñal Group - THYPHOID FEVER Draftvirgo paigeAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Hospital Infection ControlDocumento31 páginasHospital Infection ControlIndian Railways Knowledge PortalAinda não há avaliações

- Anaphy Lec Sas-17Documento4 páginasAnaphy Lec Sas-17Francis Steve RipdosAinda não há avaliações

- In Defence of Self - How The Immune System Really Works (Oxford, 2007)Documento276 páginasIn Defence of Self - How The Immune System Really Works (Oxford, 2007)Crina Cryna100% (1)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- WHO Guide For Rabies Prevention Strategy. Updated 2018Documento12 páginasWHO Guide For Rabies Prevention Strategy. Updated 2018candida samAinda não há avaliações

- Study The Following Case. Fill in The Blanks With The Correct To BeDocumento3 páginasStudy The Following Case. Fill in The Blanks With The Correct To BeAnggita Heryani FIKA 2CAinda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Catalogo Web General ENDocumento9 páginasCatalogo Web General ENmrashrafiAinda não há avaliações

- Neonatal InfectionsDocumento18 páginasNeonatal InfectionsSanthosh.S.U100% (1)

- B.B Immunology For Blood BankDocumento26 páginasB.B Immunology For Blood BankAbode AlharbiAinda não há avaliações

- Meningitis PDFDocumento8 páginasMeningitis PDFrizeviAinda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- VPD Report 2019 MayDocumento12 páginasVPD Report 2019 MaystprepsAinda não há avaliações

- REGENERATE - How To Reverse COVID Vaxx Related Injuries and Repair Damaged TissueDocumento46 páginasREGENERATE - How To Reverse COVID Vaxx Related Injuries and Repair Damaged TissuemihailuicanAinda não há avaliações

- Newly Diagnosed HIV Cases in The Philippines: National Epidemiology CenterDocumento4 páginasNewly Diagnosed HIV Cases in The Philippines: National Epidemiology CenterDeden DavidAinda não há avaliações

- Blood Transfusion Policy 6.3Documento90 páginasBlood Transfusion Policy 6.3raAinda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Introduction To ImmunologyDocumento10 páginasIntroduction To ImmunologyArvi MandaweAinda não há avaliações

- Internal MedicineDocumento277 páginasInternal MedicineAhmad Abu ArkoubAinda não há avaliações

- Tuberculosis PowerpointDocumento69 páginasTuberculosis PowerpointCeline Villo100% (1)

- Subcutaneous MycosesDocumento16 páginasSubcutaneous MycosesMohamedAinda não há avaliações

- Hemorrhagic FeverDocumento3 páginasHemorrhagic FeverDenis QosjaAinda não há avaliações

- Prevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection Among Tuberculosis Patients at Infectious Disease Hospital, Kano State, NigeriaDocumento8 páginasPrevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection Among Tuberculosis Patients at Infectious Disease Hospital, Kano State, NigeriaUMYU Journal of Microbiology Research (UJMR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Journa L Read ING: Reta Fit Riana Ku Suma 01.211. 6497Documento29 páginasJourna L Read ING: Reta Fit Riana Ku Suma 01.211. 6497Ricky ZafiriantoAinda não há avaliações