Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

RM

Enviado por

Thitamhrn0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

7 visualizações25 páginas,..

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PPT, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documento,..

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PPT, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

7 visualizações25 páginasRM

Enviado por

Thitamhrn,..

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PPT, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 25

Terminology and Classification

Four types of hypertensive disease:

•Gestational hypertension—evidence for the

preeclampsia syndrome does not develop and

hypertension resolves by 12 weeks postpartum

•Preeclampsia and eclampsia syndrome

•Chronic hypertension of any etiology

•Preeclampsia superimposed on chronic

hypertension.

Diagnosis

• Hypertension is diagnosed empirically when

appropriately taken blood pressure exceeds

140 mm Hg systolic or 90 mm Hg diastolic.

Gestational Hypertension

• Diagnosis is made in women whose blood

pressures reach 140/90 mm Hg or greater for

the first time after midpregnancy, but in

whom proteinuria is not identified.

• Gestational hypertension is reclassifed as

transient hypertesion if evidence for

preeclampsia does not develop and the blood

pressure returns to normal by 12 weeks

postpartum.

Preeclampsia Syndrome

• Preeclampsia is best described as a

pregnancy-specific syndrome that can affect

virtually every organ system.

• Appearance of proteinuria remains an

important diagnosis criterion.

• Proteinuria is an objective marker and reflects

the system-wide endothelial leak, which

characterizes the preeclampsia syndrome.

Eclampsia

• In a woman with preeclampsia, a convulsion

that cannot be attributed to another cause is

termed eclampsia.

• May appear before, during, or after labor.

Preeclampsia Superimposed on

Chronic Hypertension

• Chronic hypertensive disorder predisposes a woman to

develop superimposed preeclampsia syndrome

• Blood pressures ≥ 140/90 mm Hg before pregnancy or

before 20 weeks’ gestation, or both.

• In some women with chronic hypertension, their blood

pressure increases to obviously abnormal levels, and this is

typically after 24 weeks.

• If new-onset or worsening baseline hypertension is

accompanied by new-onset proteinuria or other findings,

then superimposed preeclampsia is diagnosed.

• Compared with “pure” preeclampsia, superimposed

preeclampsia commonly develops earlier in pregnancy. It

also tends to be more severe and often is accompanied by

fetal-growth restriction.

Etiology

Those currently considered important include:

• Placental implantation with abnormal

trophoblastic invasion of uterine vessels

• Immunological maladaptive tolerance between

maternal, paternal (placental), and fetal tissues

• Maternal maladaptation to cardiovascular or

inflammatory changes of normal pregnancy

• Genetic factors including inherited predisposing

genes and epigenetic influences.

Abnormal Trophoblastic Invasion

Immunological Factors

• Loss of maternal immune tolerance to paternally

derived placental and fetal antigens

• The histological changes at the maternal-placental

interface are suggestive of acute graft rejection.

• Some of the factors possibly associated with

dysregulation include “immunization” from a previous

pregnancy, some inherited human leukocyte antigen

(HLA) and natural killer (NK)-cell receptor haplotypes,

and possibly shared susceptibility genes with diabetes

and hypertension

Nutritional Factors

• A diet high in fruits and vegetables with

antioxidant activity is associated with

decreased blood pressure.

• Incidence of preeclampsia was doubled in

women whose daily intake of ascorbic acid

was less than 85 mg

Genetic Factors

• Incident risk for preeclampsia of 20 to 40

percent for daughters of preeclamptic

mothers;

• 11 to 37 percent for sisters of preeclamptic

women;

• 22 to 47 percent for twins.

Management

Basic management objectives for any pregnancy

complicated by preeclampsia are:

• termination of pregnancy with the least possible

trauma to mother and fetus

• birth of an infant who subsequently thrives

• complete restoration of health to the mother.

In many women with preeclampsia, especially those

at or near term, all three objectives are served

equally well by induction of labor. One of the most

important clinical questions for successful

management is precise knowledge of fetal age.

Management

• Termination of pregnancy is the only cure for

preeclampsia.

• When the fetus is preterm, the tendency is to

temporize in the hope that a few more weeks in

utero will reduce the risk of neonatal death or

serious morbidity from prematurity.

• With moderate or severe preeclampsia that does

not improve after hospitalization, delivery is

usually advisable for the welfare of both mother

and fetus.

Management for suspected severe

preeclampsia

Early Diagnosis of Preeclampsia

• Women with new-onset diastolic blood pressures > 80

mm Hg but < 90 mm Hg or with sudden abnormal

weight gain of more than 2 pounds per week includes,

at minimum, return visits at 7-day intervals.

• Outpatient surveillance is continued unless overt

hypertension, proteinuria, headache, visual

disturbances, or epigastric discomfort supervene.

• Women with overt new-onset hypertension— either

diastolic pressures ≥ 90 mm Hg or systolic pressures ≥

140 mm Hg—are admitted to determine if the increase

is due to preeclampsia, and if so, to evaluate its

severity.

Evaluation

A systematic evaluation is instituted to include the following:

• Detailed examination, which is followed by daily scrutiny

for clinical findings such as headache, visual disturbances,

epigastric pain, and rapid weight gain

• Weight determined daily

• Analysis for proteinuria or urine protein:creatinine ratio on

admittance and at least every 2 days thereafter

• Blood pressure readings in the sitting position with an

appropriate-size cuff every 4 hours, except between 2400

and 0600 (unless previous readings had become elevated )

• Measurements of plasma or serum creatinine and hepatic

aminotransferase levels and a hemogram that includes

platelet quantification

• Evaluation of fetal size and well-being and amnionic fluid

volume, with either physical examination or sonography.

Eclampsia Management

• Control of convulsions using an intravenously administered

loading dose of magnesium sulfate that is followed by a

maintenance dose, usually intravenous, of magnesium

sulfate

• Intermittent administration of an antihypertensive medica-

tion to lower blood pressure whenever it is considered

dangerously high

• Avoidance of diuretics unless there is obvious pulmonary

edema, limitation of intravenous uid administration unless

uid loss is excessive, and avoidance of hyperosmotic agents

• Delivery of the fetus to achieve a remission of

preeclampsia.

Management of Severe Hypertension

Hydralazine

• administered intravenously with a 5-mg initial

dose, and this is followed by 5- to 10-mg doses at

15- to 20-minute intervals until a satisfactory

response is achieved

• target response antepartum or intrapartum is a

decrease in diastolic blood pressure to 90 to 110

mm Hg

• target response antepartum or intrapartum is a

decrease in diastolic blood pressure to 90 to 110

mm Hg

Labetalol

•target response antepartum or intrapartum is a

decrease in diastolic blood pressure to 90 to 110

mm Hg

•10 mg intravenously initially

•If the blood pressure has not decreased to the

desirable level in 10 minutes, then 20 mg is given.

The next 10-minute incremental dose is 40 mg and

is followed by another 40 mg if needed. If a salutary

response is not achieved, then an 80-mg dose is

given. (max dose 220mg)

Hydralazine versus Labetalol

• Hydralazine caused significantly more

maternal tachycardia and palpitations,

whereas labetalol more frequently caused

maternal hypotension and bradycardia.

• Both drugs have been associated with a

reduced frequency of fetal heart rate

accelerations

Nifedipin

• Randomized trials that compared nifedipine

with labetalol found neither drug de nitively

superior to the other. However, Nifedipin

lowered blood pressure more quickly

• Recommend a 10-mg initial oral dose to be

repeated in 30 minutes if necessary

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Hoarseness and Laryngopharyngeal RefluxDocumento5 páginasHoarseness and Laryngopharyngeal RefluxThitamhrnAinda não há avaliações

- HypertensionDocumento52 páginasHypertensionpatriciajesikaAinda não há avaliações

- Pemicu 1 Endokrin MargaretDocumento60 páginasPemicu 1 Endokrin MargaretThitamhrnAinda não há avaliações

- Recap MR02-041118A: AlbertDocumento5 páginasRecap MR02-041118A: AlbertThitamhrnAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Health History QuestionnaireDocumento3 páginasHealth History QuestionnairejlaferriereAinda não há avaliações

- Traditional indian medicine.அகஸ்தியர் சித்த வைத்திய நிலையம் - AGASTHIAR ALL DIESEACESDocumento26 páginasTraditional indian medicine.அகஸ்தியர் சித்த வைத்திய நிலையம் - AGASTHIAR ALL DIESEACESDeebaAinda não há avaliações

- AMC Clinical Recalls 2019 (COMPLETE TILL JUL) - SponsoredDocumento46 páginasAMC Clinical Recalls 2019 (COMPLETE TILL JUL) - SponsoredIgor Dias67% (3)

- Introduction To Oral Pathology 1Documento32 páginasIntroduction To Oral Pathology 1Hoor M TahanAinda não há avaliações

- DM, DKA, and IDMDocumento19 páginasDM, DKA, and IDMJennyu YuAinda não há avaliações

- Vol 27.5 - Neurocritical Care.2021Documento363 páginasVol 27.5 - Neurocritical Care.2021RafaelAinda não há avaliações

- Hema 1 ErythropoiesisDocumento20 páginasHema 1 Erythropoiesismarie judimor gomezAinda não há avaliações

- Peds Ati ReviewDocumento32 páginasPeds Ati ReviewMorgan100% (41)

- English Robot Script FinalDocumento4 páginasEnglish Robot Script FinalKumaresh MuthuAinda não há avaliações

- High-Risk Newborns and Child During Illness and Hospitalization - Pediatric NursingDocumento200 páginasHigh-Risk Newborns and Child During Illness and Hospitalization - Pediatric Nursingjaggermeister20100% (8)

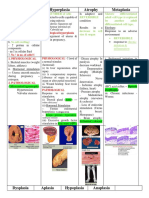

- Hypertrophy Hyperplasia Atrophy MetaplasiaDocumento20 páginasHypertrophy Hyperplasia Atrophy MetaplasiaYunQingTanAinda não há avaliações

- Muscle Weakness in Adults PDFDocumento14 páginasMuscle Weakness in Adults PDFJames TianAinda não há avaliações

- Cardiac Function Tests Anatomy of The HeartDocumento8 páginasCardiac Function Tests Anatomy of The HeartJosiah BimabamAinda não há avaliações

- Infecciones Necrotizantes de Tejidos Blandos TheLancet 2023Documento14 páginasInfecciones Necrotizantes de Tejidos Blandos TheLancet 2023Nicolás LaverdeAinda não há avaliações

- 2012 Mrcog 1 RecallsDocumento17 páginas2012 Mrcog 1 RecallsMahavir GemavatAinda não há avaliações

- Icd 10 CodeDocumento3 páginasIcd 10 Codecheryll duenasAinda não há avaliações

- Lichen Striatus Successfully Treated With Photodynamic TherapyDocumento3 páginasLichen Striatus Successfully Treated With Photodynamic TherapyOzheanAMAinda não há avaliações

- Common Symptoms of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal DiseaseDocumento34 páginasCommon Symptoms of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal DiseaseMalueth AnguiAinda não há avaliações

- Neuro UrologyDocumento53 páginasNeuro UrologymoominjunaidAinda não há avaliações

- Case Study GonorrheaDocumento19 páginasCase Study GonorrheaErika ThereseAinda não há avaliações

- 93 - 08 Bantar 7 Hal 306-312Documento7 páginas93 - 08 Bantar 7 Hal 306-312amilyapraditaAinda não há avaliações

- Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome The CurrenDocumento6 páginasSystemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome The CurrenberlianAinda não há avaliações

- Adult Referral For PC Assessment FormDocumento1 páginaAdult Referral For PC Assessment Formwhy u reading thisAinda não há avaliações

- Clinico-Radiological Profile in Covid - 19 PatientsDocumento6 páginasClinico-Radiological Profile in Covid - 19 PatientsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (1)

- Start CPR Shout For Help/Activate Emergency Response: Give Oxygen Attach Monitor/DefibrillatorDocumento2 páginasStart CPR Shout For Help/Activate Emergency Response: Give Oxygen Attach Monitor/DefibrillatorFelicia ErikaAinda não há avaliações

- Dental Pulse 12th Ed - PhysiologyDocumento107 páginasDental Pulse 12th Ed - PhysiologyLangAinda não há avaliações

- Rife FrequenciesDocumento471 páginasRife Frequencieslopans100% (9)

- Moving Exam NCM 109 Lecture For PrintDocumento6 páginasMoving Exam NCM 109 Lecture For PrintMoneto CasaganAinda não há avaliações

- Cerebral Salt Wasting Syndrome - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocumento4 páginasCerebral Salt Wasting Syndrome - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfOnggo WiliyantoAinda não há avaliações

- Sistema Curativo Por Dieta Amucosa - Arnold Ehret - WWW - Arnoldehret.infoDocumento8 páginasSistema Curativo Por Dieta Amucosa - Arnold Ehret - WWW - Arnoldehret.infoLorena CalahorroAinda não há avaliações