Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

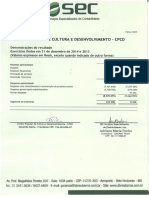

Projeto Sementinha Children in Europe

Enviado por

CPCD100%(1)100% acharam este documento útil (1 voto)

1K visualizações2 páginasProjeto Sementinha em destaque na Revista Children in Europe, junho de 2008.

Direitos autorais

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

PDF ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoProjeto Sementinha em destaque na Revista Children in Europe, junho de 2008.

Direitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF ou leia online no Scribd

100%(1)100% acharam este documento útil (1 voto)

1K visualizações2 páginasProjeto Sementinha Children in Europe

Enviado por

CPCDProjeto Sementinha em destaque na Revista Children in Europe, junho de 2008.

Direitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 2

practice

Ana Angélica Albano

reflects on the

importance of art as a

language

and how good artistic

education uncovers and

mainiains it.

Transforming reality

The river that ran behind

our house was the image

of a glass snake that

curved behind the house.

Later, a man passed by

and said: This curve that

the river makes behind

your house is called a

bow.

It was no longer the

image of a glass snake

that curved behind the

house.

It was a bow I think the

name impoverishes the

image.

Manoel de Barros

The language of art

Being invited to give many

lectures and workshops for

teachers of young children has led

me to focus on the concepts that

these educators have about

childhood and art and on the

Possibility of transforming the

approach to learning by including

poetry in art education. This arose

from my conviction that artists and

poets have much to say to those

who work with the youngest

children. They restore to education

what the child has not yet lost: the

ability to imagine glass snakes

making curves behind the house...

‘The approach taken by the

teacher is far more important than

the material resources. What

determines the practice of the

teacher is his or her “personal

aesthetic’, which has to do not

only with what the teacher likes or

‘appreciates or thinks of as

beautiful, but with the very way he

or she does things. Each

movement, gesture and decision is

intrinsically connected to the

aesthetic of each person, which,

like a fingerprint, leaves its unique

mark on everything it touches.

However, unlike a fingerprint,

which is permanent, a personal

aesthetic can be enhanced through

education.

When they take an art

course, teachers often want tips

that will help them to plan their

activities; they treat their school

as if it was a place for

consumption of recipes, and not

for the creation of knowledge. The

first step, therefore, Is to get them

to-understand that art is a

language, a form of

‘communication that says what

words cannot say. The lines,

colours, shapes and textures are

an alphabet, one of the first that

the child uses to communicate. We

can even say that it is its first

writing, because every child draws:

the stick in the sand, the stone on

the earth, the inky brush on the

paper - the playing child leaves his

mark, creating games and telling

stories. However, when they grow,

most children say they do not

know how to draw; a language

that is so natural in infancy

atrophies. Is this an inevitable part

of development?

By giving little attention to

their own aesthetic education,

teachers simply accept that

drawing is something that is lost,

or else is reserved only for those

who have a gift. They also believe

that art is always an expensive

activity, a luxury not a necessity.

Following the poem by Manoel de

Barros, we can ask ourselves: do

the melting glass snakes, when

replaced by bows, take with them

part of the world of the

imagination?

20 © Children in Scotland, Issue 14, 2008,

education

An artistic education is not about mere trensmission of

information, nor does it rely on a gift. It requires knowledge,

suitable planning and coherence. It needs to be an everyday

exercise, not confined to special days or to when there is spare

time. It requires attention to each child's level of intellectual and

emotional development, to propose an appropriate activity.

In my workshops, teachers comment that, throughout

their previous education, they have had few opportunities to

express their ideas with visual language. They realise the need

for a wide variety of experiences with different materials and

techniques. They understand, however, that a technique is only

a means, never an end in itself.

‘The youthful curiosity in making marks comes from the

need to exercise the ability to learn things, to express

discoveries and to tell stories. Far more than materials and

techniques, children need significant experiences. Not just a

wide variety of experiences, not just always something new, but

a coherent sequence of activities, presented in a way that allows

children to deepen their understanding and build significant

knowledge. The richness of the images expressed in drawings

and paintings depends on both the quantity and quality of the

experiences to which children have been exposed, as well as the

atmosphere of trust and sharing provided by the teacher during

the activities.

A visit to the park, a story or a dream can lead to a

series of related activities. On a walk, children can observe the

colours, textures, sounds and smells of the world around them,

and collect specimens. Taken back to the classroom, this

material can allow the deepening of sensory experience, the

exchange of observations, and the creation of different (or

symbolic) narratives. Later, the children can build on their

discoveries by researching in books, reading poems, telling

stories and watching films. The drawings and paintings that

result from this process will reveal the richness of the

experiences they went through.

Activities that explore the outside world, like visiting a

park, are as important as those that explore the inner world of

children, such as talking about a dream, remembering a special

event, a poem, or a favourite story. The teacher must be aware

of and listen closely to the differing perspectives and desires of

the children. It doesn’t matter whether the drawings are

beautiful or not; what matters is that they are meaningful, that

they translate the dimensions and colour of the dream of the

child that created them. The drawing, as the poetry, will then be

the result of a particular way of looking at things. It requires a

willingness to submit to the experience, because the magic of

art is that “it shows that reality can be transformed, dominated

and become a thing to play wit

Ana Angélica Albano is a professor in the Faculty of

Education at the State University of Campinas

(UNICAMP), Brazil

Semi ntinha Pr Project

ichool under the

mango tree provides for

young children outside the formal

education system. In 2001, the

project was introduced to Santo

Andre, an industrial district of Sao

Paulo, where 2000 children, aged

four to six, were not at school.

Activities included creative

workshops and “traveling stories

suitcases", suitcases filled with

children’s books. But the most

J discovery among all

the activities was the creation of

small art studios, in which children

were able to work autonomously,

freely choosing materials and

subjects for their work.

The educators were

fascinated by the wealth of ideas

from children. Another surprise

was the children’s ability to keep

the studios in good condi

Instead of guiding the work, the

team of educators was transformed

into alert observers and

collaborators, facilitating the

children’s efforts to achieve their

own projects. The educators

themselves had never experienced

such freedom of choice; they were

fascinated, but not completely

convinced about the children’s

potential. The key was trust;

trusting the processes of others,

their capacity to use materials in a

responsible way and give form to

the invisible, expressing through

images what words could never

convey.

Our aim has been to

encourage children to tell their

stories through their drawings,

demonstrating that drawing

connects them to their inner world

of images and stories. As a five-

year old girl said: “I like to draw,

because when I draw my heart

beats”. We could hardly find a

better way to describe how the

emotion of expressing ideas

bridges heart and mind.

© Children in Scotland, Issue 14, 2008 21

Você também pode gostar

- Parecer 2015 - Balanço 2013 - 2014 CPCDDocumento3 páginasParecer 2015 - Balanço 2013 - 2014 CPCDCPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Fotográfico - Vargem Grande - Jun A Ago 2014Documento19 páginasRelatório Fotográfico - Vargem Grande - Jun A Ago 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Rua Que Te Quero CriançaDocumento3 páginasRua Que Te Quero CriançaCPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Artesão: Sujeito e Objeto de Seu TrabalhoDocumento2 páginasArtesão: Sujeito e Objeto de Seu TrabalhoCPCD100% (1)

- Relatório Técnico - Vargem Grande - Mar A Mai 2014Documento49 páginasRelatório Técnico - Vargem Grande - Mar A Mai 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Técnico Vargem Grande - Jun A Ago 2014Documento19 páginasRelatório Técnico Vargem Grande - Jun A Ago 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Fotográfico - Vargem Grande - Mar A Mai 2014Documento19 páginasRelatório Fotográfico - Vargem Grande - Mar A Mai 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Fotográfico - Vargem Grande - Dez 13 A Jan 2014Documento22 páginasRelatório Fotográfico - Vargem Grande - Dez 13 A Jan 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Técnico - Casa Saudável - Out 2013 A Fev 2014Documento17 páginasRelatório Técnico - Casa Saudável - Out 2013 A Fev 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Fotográfico - Casa Saudável - Out 2013 A Fev 2014Documento46 páginasRelatório Fotográfico - Casa Saudável - Out 2013 A Fev 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Fotográfico - Raposos Sustentável - Jan A Mar 2014Documento25 páginasRelatório Fotográfico - Raposos Sustentável - Jan A Mar 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Técnico - Vargem Grande - Dez 13 A Fev 2014Documento14 páginasRelatório Técnico - Vargem Grande - Dez 13 A Fev 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Técnico - Raposos Sustentável - Jan A Mar 2014Documento49 páginasRelatório Técnico - Raposos Sustentável - Jan A Mar 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Técnico - Raposos Sustentável - Abr A Jun 2014Documento35 páginasRelatório Técnico - Raposos Sustentável - Abr A Jun 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Fotográfico - Vargem Grande - Dez 13 A Jan 2014Documento22 páginasRelatório Fotográfico - Vargem Grande - Dez 13 A Jan 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Fotográfico - Vargem Grande - Jun A Ago 2014Documento19 páginasRelatório Fotográfico - Vargem Grande - Jun A Ago 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Técnico Ação Curvelo - Jan A Mar 2014Documento19 páginasRelatório Técnico Ação Curvelo - Jan A Mar 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Fotográfico Ação Curvelo - Jan A Mar de 2014Documento24 páginasRelatório Fotográfico Ação Curvelo - Jan A Mar de 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Técnico Ação Curvelo - Abr A Jun 2014Documento13 páginasRelatório Técnico Ação Curvelo - Abr A Jun 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Fotográfico Ação Curvelo - Abr A Jun 2014Documento22 páginasRelatório Fotográfico Ação Curvelo - Abr A Jun 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Técnico - Vargem Grande - Dez 13 A Fev 2014Documento14 páginasRelatório Técnico - Vargem Grande - Dez 13 A Fev 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Fotográfico - Vargem Grande - Mar A Mai 2014Documento19 páginasRelatório Fotográfico - Vargem Grande - Mar A Mai 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Técnico Vargem Grande - Jun A Ago 2014Documento19 páginasRelatório Técnico Vargem Grande - Jun A Ago 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Informativo ARASEMPRE - Ano7 - No. 125Documento14 páginasInformativo ARASEMPRE - Ano7 - No. 125CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Informativo Casa Saudável - Ano 1 - Nº 1Documento8 páginasInformativo Casa Saudável - Ano 1 - Nº 1CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório Técnico - Vargem Grande - Mar A Mai 2014Documento49 páginasRelatório Técnico - Vargem Grande - Mar A Mai 2014CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Informativo Nos Trilhos Do Desenvolvimento - #3 - 13Documento11 páginasInformativo Nos Trilhos Do Desenvolvimento - #3 - 13CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Informativo Raposos Sustentável - Ano 6 - Nº 62Documento9 páginasInformativo Raposos Sustentável - Ano 6 - Nº 62CPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Estado de Minas 13.04.14 Tião RochaDocumento1 páginaEstado de Minas 13.04.14 Tião RochaCPCDAinda não há avaliações

- Nos Trilhos Do Desenvolvimento - Ano 1 - Nº 12Documento11 páginasNos Trilhos Do Desenvolvimento - Ano 1 - Nº 12CPCDAinda não há avaliações