Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Docentes PDF

Docentes PDF

Enviado por

conanatoTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Docentes PDF

Docentes PDF

Enviado por

conanatoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Review

Direct and indirect vocal interventions for teachers: a

systematic review of the literature

Intervenes vocais diretas e indiretas em professores: reviso

sistemtica da literatura

Tanise Cristaldo Anhaia1, Lia Gonalves Gurgel2, Raquel Hochmuller Vieira3, Mauriceia Cassol4

ABSTRACT

RESUMO

Purpose: The aim of this work is to verify the efficacy of direct and

Objetivo: Verificar a eficcia das intervenes vocais diretas e indiretas,

indirect vocal interventions in preventing voice disorders, with speci-

de forma isolada e combinada, na preveno de distrbios vocais em

fic and combined strategies, by a systematic review of the literature.

professores, por meio de reviso sistemtica da literatura. Estratgias

Research strategies: Articles published from January, 1980 to April,

de pesquisa: Foram pesquisados artigos de janeiro de 1980 a abril de

2013 were searched in the electronic databases MEDLINE (accessed

2013, nas bases de dados eletrnicas MEDLINE (acessado pelo Pub-

through PubMed), PubMed, LILACS, SciELO, Scopus and Web of

Med), PubMed, LILACS, SciELO, Scopus e Web of Science. Critrios

Science. Selection criteria: All the articles that presented randomized

de seleo: Foram includos todos os artigos que tinham como objetivo

controlled studies with some type of vocal intervention with teachers

principal algum tipo de interveno com professores e que fossem en-

as their primary aim were included. Articles that presented subjects

saios controlados randomizados. Excluu-se artigos que apresentavam

with larynx and voice alterations were excluded. Results: As a result

indivduos com alteraes de laringe e voz e que estivessem afastados

of the initial search, 677 studies were identified, five of which followed

de sua profisso. Resultados: Como resultado da busca inicial, foram

the inclusion criteria. Four more articles, found in the references of the

identificados 677 estudos, dentre os quais, cinco atendiam aos critrios

studies selected for reading of the full text, were included. Conclusion:

de incluso. Somou-se a esses mais quatro artigos, encontrados nas refe-

The combined intervention (direct and indirect) presented a significant

rncias bibliogrficas dos estudos selecionados para a fase de leitura do

improvement in vocal quality parameters and self-assessment, even in

texto completo. Concluso: A interveno combinada (direta e indireta)

a short period of time. In other studies, which focused on the compa-

apresentou melhora significativa em parmetros da qualidade vocal e na

rison between combined and specific interventions (direct or indirect),

autoavaliao da voz, mesmo em curto perodo de tempo. Em outros

no differences were observed, although improvements in some of the

estudos, cujo foco era a comparao entre a interveno combinada e in-

assessed vocal parameters were described. A limitation of this review is

tervenes isoladas (direta ou indireta), no foram observadas diferenas

the restriction of the methodological design of the studies, including only

significativas, apesar de serem descritas melhoras em alguns dos par-

randomized clinical trials. The combined vocal intervention presented

metros vocais avaliados. Como limitao desta reviso, pode-se incluir a

more significant results than the specific intervention.

restrio quanto ao desenho metodolgico dos estudos, incluindo apenas

ensaios clnicos randomizados. A interveno vocal combinada apresenta

Keywords: Voice; Faculty; Voice Training; Voice Disorders; Larynx;

resultados mais expressivos do que a interveno isolada.

Occupational Health

Descritores: Voz; Docentes; Treinamento da Voz; Distrbios da Voz;

Laringe; Sade do Trabalhador

This work was performed at Universidade Federal de Cincias da Sade de Porto Alegre UFCSPA Porto Alegre (RS), Brazil.

(1) Post-Graduate Program (Masters degree) in Rehabilitation Sciences Universidade Federal de Cincias da Sade de Porto Alegre UFCSPA Porto Alegre

(RS), Brazil.

(2) Post-Graduate Program (Masters degree) in Health Sciences, Universidade Federal de Cincias da Sade de Porto Alegre UFCSPA Porto Alegre (RS), Brazil.

(3) Speech, Language, Pathology and Audiology Course, Universidade Federal de Cincias da Sade de Porto Alegre UFCSPA Porto Alegre (RS), Brazil.

(4) Post-Graduate Program in Rehabilitation Sciences, Universidade Federal de Cincias da Sade de Porto Alegre UFCSPA Porto Alegre (RS), Brazil.

Conflict of interests:No

Authors contribution: TCA: main researcher, study conception and design, development of research schedule, literature search, acquisition of data, analysis and

interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, manuscript submission; LGG: study conception and design, development of research schedule, literature search,

acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, manuscript submission; RHV: study conception and design, development of research

schedule, literature search, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, manuscript submission; MC: general supervision of the

research, manuscript correction, critical revision, final approval of the version.

Correspondence address: Tanise Cristaldo Anhaia. R. Riachuelo 1290/1004, Porto Alegre (RS), Brazil, CEP: 90010-270. E-mail: tanisecristaldo@hotmail.com

Received: 4/29/2013; Accepted: 9/4/2013

ACR 2013;18(4):361-6

361

Anhaia TC, Gurgel LG, Vieira RH, Cassol M

INTRODUCTION

RESEARCH STRATEGY

Considered a relevant factor for the socializing process,

the voice can have an impact on a persons quality of life,

especially when it is used professionally(1). Therefore, researches involving the professional use of the voice have received

increasing attention in recent years(2,3). It is known that teachers

present a higher risk of developing vocal alterations compared

with subjects from the general population(4), and at least 50%

of them regularly suffer from voice disorders, limiting their

performance at work(5).

The aim of voice care, both in prevention and treatment, is to

recover the voice, making it functional for professional use and

communication in general. Thus, the interventions designed to

prevent voice disorders can be divided into direct and indirect

strategies(6). The direct strategy provides a change in the vocal

functioning, offering vocal technique instructions, in order to

stimulate a more effective voice production, thereby protecting

the individual from developing voice disorders. On the other

hand, the indirect strategy helps the individual to understand the

use of the voice, the psychological and environmental factors

that can lead to voice alterations, and to develop strategies to

minimize such risk factors(4).

Voice training and therapy aim at preventing and treating

voice disorders by changing vocal habits. The voice training makes the use of the voice easier, avoids vocal fatigue

and inadequate practice and provides a better preparation to

perform the activity which requires the use of the voice(7).

Furthermore, voice training exercises increase the blood

flow and improve breathing, allowing the increase of muscle

contractions and elasticity(8). Several studies have shown

positive effects of voice therapy and training in parameters

assessed by acoustic and auditory-perceptual analyses in terms

of decreased perturbation (jitter and shimmer), increased

signal-to-noise ratio and a better vocal quality(9). However,

few prevention programs are designed for teachers and future

teachers(7).

Considering that the vocal assessment has been privileged

in Brazilian researches(10), studies on the effects of interventions on such professionals are more recent. They can provide

a better understanding of the complex reality of voice use in

teaching and guide future interventions. Systematic reviews

are recognized as important in health sciences and, although

not frequent in Speech, Language Pathology and Audiology,

they have increased in the last decade, highlighting that topics

and new perspectives from these analyses should be taken into

consideration.

The following electronic databases were searched for articles published from January, 1980 to April, 2013: MEDLINE

(accessed through PubMed), PubMed, LILACS, SciELO,

Scopus and Web of Science. The search terms were: voice,

faculty and randomized controlled trial and their related terms

in Portuguese, English and Spanish. Words regarding the outcomes of interest were not included, in order to increase the

sensitivity of the search. There was no restriction regarding the

types of interventions employed in the studies.

OBJECTIVES

The objective of this study is to verify the efficacy of direct

and indirect vocal interventions, with specific and combined

strategies, in preventing voice disorders in teachers.

362

SELECTION CRITERIA

All randomized controlled trials that presented some type

of vocal intervention with teachers as their primary aim were

included. We chose to restrict the experimental design, since

randomized clinical trials are the most reliable source of scientific evidence and allow the greatest validity of the results

in a systematic review. Exclusion criteria for this review were:

studies that included subjects with previous larynx and voice

alterations, and studies with teachers who were no longer in

professional activity or away from work for some reason. There

was no age limit, nor restrictions of gender and intervention

time.

DATA ANALYSIS

In the first phase, the titles and abstracts of all the articles

identified through the search strategy were assessed by the

investigators. In the next phase, all the abstracts that did not

present enough information regarding inclusion and exclusion

criteria and contained information about interventions for

teachers were selected for assessment of the full text. In the

third phase, the assessment of the full texts was performed by

two previously trained reviewers, who independently rated

the articles, filling out a standardized form and selecting them

according to the eligibility criteria. The references sections of

these articles were also reviewed, aiming to find works that,

for some reason, had not shown up in the initial search. The

discordances, in every phase, were settled by consensus. Then,

the primary data regarding the method of vocal intervention

for teachers were collected.

The quality of the studies was assessed using the Cochrane

Handbook(11), which classifies the studies into A, B, or C,

according to low, moderate or high risk of biased primary

studies, respectively. Such classification is based on the internal validity of the studies, the randomization procedures

and the way of preventing bias. The quality assessment was

complemented with the use of the Jadad scale(12), an instrument for quality assessment, which consists of five questions

regarding randomization, masking, double blinding, losses

and exclusions.

ACR 2013;18(4):361-6

Vocal interventions for teachers

RESULTS

As a result of the initial search, 677 studies were identified,

among which five(5,9,13-15) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were

considered relevant for the sample of this work. Four more articles(3,4,16,17), found in the references of the studies selected for

the reading of the full text, were added as additional references.

Therefore, a total of nine articles were included in this review

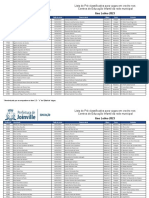

for a more rigorous analysis (Figure 1).

All the articles were published in English, and 44.4% of

the studies were carried out in Finland. In the nine studies,

543 subjects with mean ages between 24 and 42 years were

included. Some studies(3,9,13,16), with poor to good quality, included only female subjects. Self-evaluation of voice was the

most employed parameter (in 87,5% of the studies) to assess

the effects of the interventions.

The main characteristics of the included studies, such as

authors, year of publication, country of origin, original language, type of intervention, number of participants, and age and

gender of the sample, are given in Table 1.

The quality of the studies ranged from poor to good, as

shown in the complete assessment (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In the literature, some classical studies(5,13) recommend

direct interventions, which apply directly to the vocal tract,

and indirect interventions, such as consulting or education on

voice hygiene and improvement of acoustic conditions of the

workplace(6).

Four studies included in this review compared direct and

indirect vocal interventions(4,5,11,13). One of them(13) verified

the effect of vocal intervention for women, assessed by self-evaluation, after direct and indirect voice training. The authors

observed that both interventions presented positive effects.

However, they were not effective in improving the participants

self-perception of vocal function. The authors suggested that

it would be interesting to investigate the effects of increased

time of training in improving the knowledge of the participants

about voice care.

Another research(4) investigated the effectiveness of orientations for voice hygiene and vocal function exercises in reducing

vocal symptoms in primary school teachers. The subjects of the

Figure 1. Diagram of article selection

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies included in this review

Authors and year

Laukkanen et al.

(2009)

Timmermans et

al. (2011)

Gillivan-Murphy et

al. (2006)

Duffy & Hazlett

(2004)

Bovo et al. (2006)

Leppnen et al.

(2009)

Leppnen et al.

(2010)

Pasa et al. (2007)

Ilomaki et al.

(2008)

Country of

origin

Finland

language

English

Original

Journal (impact factor)

Intervention type

Direct and indirect

English

Folia Phoniatrica et

Logopaedica (0.726)

Journal of Voice (1.108)

n (mean age of

the sample)

n=90 (41.1 years)

Belgium

Direct and indirect

n=65 (na)

Ireland

English

Journal of Voice (1.108)

Direct and indirect

n=20 (40 years)

Ireland

English

Journal of Voice (1.108)

Direct and indirect

Italy

English

Journal of Voice (1.108)

Direct and indirect

Finland

English

Direct and indirect

Finland

English

Direct and indirect

n=90 (41 years)

Australia

English

Direct and indirect

n=39 (38 years)

Finland

English

Folia Phoniatrica et

Logopaedica (0.726)

Logopedics Phoniatrics

Vocology (0.83)

Logopedics Phoniatrics

Vocology (0.83)

Logopedics Phoniatrics

Vocology (0.83)

n=55 (between 24

and 25 years)

n=64 (between 38

and 39 years)

n=60 (40.6 years)

Direct and indirect

n=60 (42 years)

Gender

F=90

M=0

F=43

M=22

F=na

M=na

F=na

M=na

F=na

M=na

F=60

M=0

F=90

M=0

F=36

M=3

F=60

M=0

Note: na = not available; F = female; M = male

ACR 2013;18(4):361-6

363

Anhaia TC, Gurgel LG, Vieira RH, Cassol M

Table 2. Asessment of quality of the studies

Study (year)

Duffy e Hazlett (2004)

Bovo et al. (2006)

Leppanen et al. (2009)

Laukkanen et al. (2009)

Timmermans et al. (2011)

Gillivan-Murphy et al. (2006)

Leppanen et al. (2010)

Pasa et al. (2007)

Ilomaki et al. (2008)

Randomization

Allocation

Concealment of

sequence

allocation

A

B

A

B

A

B

A

B

A

B

A

C

A

B

A

B

A

B

Masking

Loss to follow up

Jadad scale (1996)

B

C

C

B

C

B

B

B

B

B

A

C

C

B

B

C

A

A

3

3

2*

2*

3

3

2*

3

3

*poor classification according to the Jadad Scale (1996)

Note: A = appropriate description; B = not descripted; C = inappropriate description

group which received orientation and performed vocal function

exercises reported an improvement in vocal characteristics and

voice knowledge after the intervention. The control group, however, showed persistent difficulties in voice knowledge, vocal

behavior at work, vocal symptoms and maximum phonation

time. The indirect intervention was significantly more beneficial

when compared to the direct intervention. However, this results

are in disagreement with the findings in the literature(5), which

showed that voice hygiene interventions are not as effective as

voice training programs, with or without voice care orientation.

A research(17) carried out in Finland concluded that vocal

function exercises are more effective than isolated voice hygiene instructions. The group that performed vocal exercises

presented a reduction in the fundamental frequency and in the

means of jitter and shimmer, along with easier phonation and

improved vocal quality. On the other hand, the group which

received orientations about voice hygiene presented a higher

fundamental frequency and increased difficulty of phonation.

Such result can be explained by the fact that voice hygiene

only provides orientation on voice care, and the effectiveness

of this type of intervention depends on the subjects ability to

assimilate the information and put it into practice during the

professional use of the voice.

Other studies included in our review assessed the effectiveness of combined direct and indirect interventions. In

one study(14) there were no clinically significant differences

between the experimental and the control groups regarding

auditory-perceptual assessment. However, for voice quality

parameters, measured by the Voice Symptom Severity Index(18),

several significant differences were identified. The subjects in

the voice training group were able to increase their vocal range

and alter the vocal behavior. The authors concluded that even a

short combined voice training program can present a positive

impact in teachers voices. Yet it was not clear to which extent

a longer training program might show promising results.

A study(15) indicated that the combination of direct and indirect voice training results in better reports from the subjects

regarding their voice symptoms and voice care, as well as a

364

significant improvement of voice symptoms and knowledge,

especially when the therapist works with a small group of subjects. The authors also suggest that the therapists qualities may

be a determining variable for the effectiveness of the treatment.

In one research(5), the effectiveness of combined voice training was demonstrated, although the positive effect was slightly

reduced one year after the course. The experimental group

presented amelioration in aspects such as global dysphonia,

maximum phonation time, jitter and shimmer. There were no

significant differences in glottal-to-noise excitation ratio and

fundamental frequency. The authors highlight that better acoustics of classrooms, use of sound amplification devices during

professional activity and voice orientation programs are essential

aspects for the primary prevention of voice disorders in teachers.

Other studies(3,9,16) aimed to compare direct, indirect and

combined vocal interventions. In the first study(3), the groups

which received voice massage, voice training and lectures on

voice hygiene did not differ in the 6 and 12 months follow-ups.

The group that received only orientations presented satisfactory

results regarding voice hygiene knowledge. The group that

received voice training emphasized, at first, the importance

of adequate voice production and vocal rest, and, after 12

months, the importance of adequate voice use. All the groups

presented reduced vocal fatigue symptoms one year after the

course, showing that, in different degrees, every intervention

is worthy for the improvement of teachers vocal well-being.

In another research(9), positive effects were reported after all

the interventions, though more significantly after voice training

and massage than after a lecture on voice hygiene. The result

of self-evaluation before and after a working day, however,

was not able to show a significant effect of the interventions.

A study(16) revealed that the group which received orientations on voice hygiene and the group which received voice

massage did not differ when compared to the self-evaluation

and to the perceptual and electro-acoustical voice parameters.

This can be due to the short duration of the intervention, which

is an important variable to verify the effectiveness. Positive effects were significantly reported after voice massage, leading to

ACR 2013;18(4):361-6

Vocal interventions for teachers

the conclusion that this type of treatment may help the teachers in maintaining their vocal well-being during professional

activity. One limitation of this study may be the absence of a

control group.

In this review, it was possible to observe that in part of the

researches(3,9,13,16) there were only female subjects. This is due

to the fact that, in addition to women being the majority in this

profession, teachers are known to present elevated prevalence of

voice disorders due to their occupation. Professional activities

demand the prolonged use of the voice, frequently loudly and

in acoustically unfavorable places. A gender difference was

observed(3), showing that the larynx and vocal folds structures

may also be a cause for the vulnerability of women to voice

disorders and vocal fold trauma. The insufficient adduction in

the dorsal part of the vocal folds and the curved shape of the

edge increase the mechanical stress in the anterior third, where

nodules can develop. A reduced amount of hyaluronic acid was

observed on the surface of womens vocal folds, in comparison

to mens, being implicated in less protection against mechanical

trauma to the vocal folds.

The evaluation of voice symptoms and voice-related quality

of life was also used to compare the results before and after the

voice interventions, since it is possible, through self-assessment

questionnaires, to analyze the impact of the alterations in the

quality of life of individuals with voice symptoms, according

to gender, age and professional voice use(6). Furthermore, the

individuals can be classified as having healthy or dysphonic

voices(19). For reliable results of the intervention effectiveness,

it is essential to combine the use of self-evaluation questionnaires, auditory-perceptual analyses and acoustic parameters.

Some studies(5,17) observed an increase in maximum phonation

time, but such measure cannot be considered relevant in the

clinical sense, since there is no confirmed relation between this

parameter and voice disorders(20).

In every study included in this review, the subjects had

professional supervision while performing the exercises.

The experience of the professional was revealed to be an important factor for the interventions(16). In this regard, there is

little information in the literature, especially in Brazil, where

a large number of researches have been carried out with this

population. The prevailing studies, however, emphasize vocal

assessments(10).

Despite the fact that teachers have a prolonged use of

the voice and frequently use it with high intensity due to the

classroom acoustics, there are no complete and reliable data

from researches performed in ideal conditions about the most

adequate intervention strategies for this public, as shown by

our review. Few randomized clinical trials were found on this

matter, although the search strategy was broad.

From the studies we have found, we concluded that the

combined (direct and indirect) intervention presented a

significant improvement in voice quality parameters and voice

self-evaluation. In studies that focused on the comparison

ACR 2013;18(4):361-6

between combined and specific (direct or indirect) interventions,

we could observe that the specific intervention did not present

significant differences, although there were improvements

in some of the parameters assessed. In another study(6), there

was no evidence of efficacy of direct or indirect training, or

a combination of both, in ameliorating vocal performance or

voice self-assessment when compared to the group that did not

receive interventions, showing that more studies are required,

with an appropriate methodology and a measurement of results

that better reflects the aim of the interventions.

To assess the quality of the studies, the CONSORT

(Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) statement was

employed. The quality ranged from poor to very good, as shown in Table 2. This data show the need for efforts to perform

more researches in ideal conditions. Among the limitations of

this review is the restriction of the methodological design of the

studies, including only randomized clinical trials. Other reviews

could be important, including other professionals who need an

effective vocal performance during work and present intensive

voice use, such as telephone operators(6,17). No systematic reviews

about preventive vocal interventions with teachers were found,

emphasizing the lack of national and international literature on

this subject. Moreover, although the restricted number of articles

included in this review does not allow a generalization of the

data, it highlights the relevance of the results.

CONCLUSION

This study elucidated the types of vocal interventions used

with teachers and their main features. We observed that the combined strategy revealed more expressive results when compared

to the specific intervention and, also, that the effectiveness of

voice training in preventing voice disorders in teachers has not

been widely studied.

The quality of the studies ranged from poor to good and

there were some limitations, such as the low number of publications in the field, the sample sizing and the short duration

of the interventions. None of the studies took place in Brazil,

highlighting the lack of randomized controlled clinical trials

with prospect for prevention in the Brazilian population. It is

important to notice that this fact may be due to the reduced number of studies on this subject under ideal research conditions,

or some studies could have been non-indexed in the searched

databases. Therefore, we emphasize the need for more researches under ideal conditions, both national and international,

in order to facilitate the choice for the most adequate types of

interventions for people who use their voices professionally.

REFERENCES

1. Henry MM, Johnson J, Foshea B. The effect of specific versus

combined warm-up strategies on the voice. J Voice. 2009; 23(5):57276.

365

Anhaia TC, Gurgel LG, Vieira RH, Cassol M

2. Hazlett DE, Duffy OM, Moorhead SA. Review of the impact of voice

DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of

training on the vocal quality of professional voice users: implications

randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials.

for vocal health and recommendations for further research. J Voice.

1996;17(1):1-12.

2011;25(2):181-91.

3. Leppanen K, Ilomaki I, Laukkanen AM. One-year follow-up study

of self-evaluated effects of voice massage, voice training, and voice

hygiene lecture in female teachers. Logoped Phoniatr Vocol. 2010;

35(1):13-8.

4. Pasa G, Oates J, Dacakis G. The relative effectiveness of vocal

13. Duffy OM, Hazlett DE. The impact of preventive voice care

programs for training teachers: a longitudinal study. J Voice.

2004;18(1):63-70.

14. Timmermans B, Coveliers Y, Meeus W, Vandenabeele F, Looy LV,

Wuyts F. The effect of a short voice training program in future

teachers. J Voice. 2011;25(4):191-8.

hygiene training and vocal function exercises in preventing voice

15. Gillivan-Murphy P, Drinnan MJ, ODwyer TP, Ridha H, Carding P.

disorders in primary school teachers. Logoped Phoniatr Vocol.

The effectiveness of a voice treatment approach for teachers with

2007;32(3):128-40.

self-reported voice problems. J Voice. 2006;20(3):423-31.

5. Bovo R, Galceran M, Petruccelli J, Hatzopoulos S. Vocal problems

16. Leppanen K, Laukkanen AM, Ilomaki I, Vilkman E. A comparison

among teachers: evaluation of a preventive voice program. J Voice.

of the effects of voice massage and voice hygiene lecture on

2007;21(6):705-22.

self-reported vocal well-being and acoustic and perceptual

6. Ruotsalainen JH, Sellman J, Lehto L, Jauhiainen M, Verbeek JH.

. Interventions for preventing voice disorders in adults. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev. 2007;17(4):CD006372.

speech parameters in female teachers. Folia Phoniatr Logop.

2009;61(4):227-38.

17. Ilomaki I, Laukkanen A M, Leppanen K, Vilkman E. Effects of voice

7. Van Lierde KM, Dhaeseleer E, Baudonck N, Claeys S, De Bodt M,

training and voice hygiene education on acoustic and perceptual

Behlau M. The impact of vocal warm-up exercises on the objective

speech parameters and self-reported vocal well-being in female

vocal quality in female students training to be speech language

pathologists. J Voice. 2011;25(3):115-21.

8. Milbrath RL, Solomon NP. Do vocal warm-up exercises alleviate

vocal fatigue? J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2003;46(2):422-36.

9. Laukkanen AM, Leppnen K, Ilomki I. Self-evaluation of voice as

a treatment outcome measure. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2009;61(1):5765.

10. Dragone MLS, Ferreira LP, Giannini SPP, Zenari MS, Vieira VP,

Behlau M. Voz do professor: uma reviso de 15 anos de contribuio

fonoaudiolgica. Rev Soc Bras Fonoaudiol. 2010;15(2):289-96.

teachers. Logoped Phoniatr Vocol. 2008;33(2):83-92.

18. Wuyts FL, De Bodt MS, Molenberghs G, Remacle M, Heylen L,

Millet B, et al. The dysphonia severity index: an objective measure

of vocal quality based on a multiparameter approach. J Speech Lang

Hear Res. 2000;43(3):796-809.

19. Behlau M, Oliveira G. Validation of self-assessment protocols

in languages different from the original version. In: 27th World

Congress of the International Association of Logopedics and

Phoniatrics. Dinamarca; 2007.

20. Roy N, Merrill RM, Thibeault S, Gray SD, Smith EM. Voice

11. Oxman A, Clarke M, editors. Cochrane reviewers handbook 4.1.1:

disorders in teachers and the general population: effects on work

updated december 2000. In: Assessment of study quality. Oxford:

performance, attendance, and future career choices. J Speech Lang

The Cochrane Library; 2001.p.39-50.

Hear Res 2004;47(3):542-51.

12. Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds

366

ACR 2013;18(4):361-6

Você também pode gostar

- Helene Contribuição Ao Estuda Da Corrosão em Armaduras de Concreto ArmadoDocumento249 páginasHelene Contribuição Ao Estuda Da Corrosão em Armaduras de Concreto ArmadoGabriel Queiroz100% (1)

- 0510 - Variação Morfossintática e Ensino de PortuguêsDocumento32 páginas0510 - Variação Morfossintática e Ensino de PortuguêsDavidson AlvesAinda não há avaliações

- Estatuto Aluno DLR n12 2013 ADocumento14 páginasEstatuto Aluno DLR n12 2013 ACarla GançoAinda não há avaliações

- Orientações Básicas Da Administração de PessoalDocumento222 páginasOrientações Básicas Da Administração de PessoalFernando De Paula100% (1)

- Edital Tutor UFSCarDocumento6 páginasEdital Tutor UFSCarFelipe HarterAinda não há avaliações

- Dissertacao Christian FernandoDocumento183 páginasDissertacao Christian FernandoMacabéa HolydayAinda não há avaliações

- Lista de Pre Classificacao para Educacao Infantil 2023 Rede Municipal 01032023Documento48 páginasLista de Pre Classificacao para Educacao Infantil 2023 Rede Municipal 01032023Iara Anaitis CresquiAinda não há avaliações

- A Feminilidade Que Se Aprende PDFDocumento202 páginasA Feminilidade Que Se Aprende PDFFabiana RuizAinda não há avaliações

- Diretrizes para Autores SBL ArchaiDocumento3 páginasDiretrizes para Autores SBL ArchaiDaniel Santibáñez GuerreroAinda não há avaliações

- Apostila 32 4º AnoDocumento16 páginasApostila 32 4º AnoMaria Conceicao0% (1)

- Planejamento Participativo IiDocumento4 páginasPlanejamento Participativo IiSidney LopesAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Deficiencia-Multipla-Conceito-E-Caracterizacao PDFDocumento14 páginas2 Deficiencia-Multipla-Conceito-E-Caracterizacao PDFDarci ShawAinda não há avaliações

- Planilha de Carga Horária ES IIIDocumento4 páginasPlanilha de Carga Horária ES IIIbenicioAinda não há avaliações

- Diario 1408Documento49 páginasDiario 1408Everton CalegariAinda não há avaliações

- Projeto Do Pibid Participacao Da Escola No Evento de Letras Agosto 2023 Assinado-1Documento3 páginasProjeto Do Pibid Participacao Da Escola No Evento de Letras Agosto 2023 Assinado-1Evandro AristimunhaAinda não há avaliações

- Plano Atividades OutubroDocumento2 páginasPlano Atividades OutubroO CARACOLAinda não há avaliações

- Caderno Estagio e FundamentalDocumento14 páginasCaderno Estagio e FundamentalAlana GabrielaAinda não há avaliações

- Questionário Educação Ambiental 1Documento5 páginasQuestionário Educação Ambiental 1Rafael CostaAinda não há avaliações

- Caminhos Pedagógicos Da InclusãoDocumento10 páginasCaminhos Pedagógicos Da InclusãoEdivania TenórioAinda não há avaliações

- 4 13 Andragogia EducacaodeadultosDocumento9 páginas4 13 Andragogia EducacaodeadultosJosimar Tomaz de BarrosAinda não há avaliações

- Vestibular 2019 Prova TardeDocumento13 páginasVestibular 2019 Prova TardeclovisjrAinda não há avaliações

- 'Sua Avó Entende A Sua Tese - ' - Os Equívocos Do MemeDocumento7 páginas'Sua Avó Entende A Sua Tese - ' - Os Equívocos Do MemeLaura Dela SáviaAinda não há avaliações

- LIVRO Jogos Brinquedos e Brincadeiras PDFDocumento36 páginasLIVRO Jogos Brinquedos e Brincadeiras PDFAntonione X Eriane AntunesAinda não há avaliações

- 1842-Texto Do Artigo-5042-1-10-20201214Documento4 páginas1842-Texto Do Artigo-5042-1-10-20201214Paula LimaAinda não há avaliações

- Educação, Relações Étnico-Raciais e A Lei 10.639 - 03 - A Cor Da CulturaDocumento4 páginasEducação, Relações Étnico-Raciais e A Lei 10.639 - 03 - A Cor Da CulturaTaliego De Sousa OliveiraAinda não há avaliações

- Memorial PDFDocumento4 páginasMemorial PDFBárbara HeloháAinda não há avaliações

- Planificação AE - Maximo 5Documento11 páginasPlanificação AE - Maximo 5Helena Borralho100% (1)

- John Finnis-Bem ComumDocumento145 páginasJohn Finnis-Bem ComumViniciusSilvaAinda não há avaliações

- Minderico-Uma Lingua Que Eh Falada em PortugalDocumento1 páginaMinderico-Uma Lingua Que Eh Falada em PortugalnunoAinda não há avaliações

- Exercicios de EstatisticaDocumento7 páginasExercicios de EstatisticaPaulino AdaoAinda não há avaliações