Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Exposio Virtual Medo de Dirigir

Enviado por

Érica FerreiraDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Exposio Virtual Medo de Dirigir

Enviado por

Érica FerreiraDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

35

Psicologia:TeoriaePesquisa

JanMar2010,Vol.26n.1,pp.3542

ExposioporRealidadeVirtualnoTratamentodoMedodeDirigir

1

RafaelThomazdaCosta

2

MarceleReginedeCarvalho

AntonioEgidioNardi

UniversidadeFederaldoRiodeJaneiro

InstitutoNacionaldeCinciaeTecnologiaTranslationalMedicine(CNPq)

RESUMOUmcrescentenmerodepesquisastmsurgidosobreaaplicaodaterapiadeexposioporrealidadevirtual

(VRET) para transtornos ansiosos. O obietivo deste estudo Ioi revisar as evidncias que apoiam a efcacia da VRET para tratar

Iobia de dirigir. Os estudos Ioram identifcados por meio de buscas computadorizadas (PubMed/Medline. Web oI Science e

Scielo databases) no periodo de 1984 a 2007. Alguns achados so promissores. Indices de ansiedade/evitaco cairam entre o

inicio e o fm do tratamento. VRET poderia ser um primeiro passo no tratamento da Iobia de dirigir. uma vez que pode Iacilitar

a exposico ao vivo. evitando-se os riscos e elevados custos dessa exposico. Entretanto. mais estudos clinicos randomizados/

controlados so necessarios para comprovar sua efcacia.

Palavraschave:revisorealidadevirtualfobiadedirigir.

VirtualRealityExposureTherapyintheTreatmentofDrivingPhobia

ABSTRACTAgrowingnumberofresearcheshasappearedonvirtualrealityexposuretherapy(VRET)totreatanxiety

disorders. The purpose oI this article was to review the evidences that support the VRET eIfcacy to treat driving phobia. The

studies were identifed through computerized search (PubMed/Medline. Web oI Science. and Scielo databases) Irom 1984 to

2007. Some fndings are promising. Anxiety/avoidance ratings declined Irom pre to post-treatment. VRET may be used as a

frst step in the treatment oI driving phobia. as long as it may Iacilitate the invivo exposure. thus reducing risks and high costs

oI such exposure. Notwithstanding. more randomized/controlled clinical trials are required to prove its eIfcacy.

Keywords:reviewvirtualrealitydrivingphobia.

1 Este trabalho recebeu o apoio do Conselho Brasileiro de Desenvolvi-

mento Cientifco e Tecnologico (CNPq). Processo: 554411/2005-9. e

do Instituto Nacional de Cincia e Tecnologia - Translational Medicine

- INCT-TM (CNPq).

2 Endereco para correspondncia: Instituto de Psiquiatria. Universidade

Federal do Rio de Janeiro. R. da Matriz. 336/201. Centro. So Joo

de Meriti. RJ. CEP 25520-640. Tel: (21) 2756-0965 / (21) 9509-4461.

Email:faelthomaz@ig.com.br.

Driving is a skill that Irequently Iacilitates the mainte-

nance oI independence and mobility. and enables contact

with a wide variety oI important activities (Taylor. Deane &

Podd. 2002).

Driving phobia is a serious social and personal

issue. This Iear-related avoidance has serious consequences

such a restriction oI Ireedom. career impairments and social

embarrassment (Ku. Jang. Lee. Lee. Kim & Kim. 2002).

Driving phobia is defned as a specifc phobia. situational

type. in the DSM-IV (APA. 1994). It is characterized by

intense. persistent Iear oI driving. which increases as the

individual anticipates. or is exposed to driving stimuli. People

withdrivingphobiarecognizethattheirfearsareexcessive

or unreasonable. However. they are either unable to drive or

tolerate driving with considerable distress (Wald & Taylor.

2000). Driving phobia does not typically decrease or beco-

messpontaneouslyasymptomaticwithouttreatmentandcan

become chronic (Mayou. Tyndel & Bryant. 1997; Taylor &

Deane. 1999; Wald & Taylor. 2003). This specifc phobia

typically occurs in young to middle adult Iemales (Ehlers.

HoImann. Herda & Roth. 1994; Taylor & Deane. 1999).

The maiority oI research points to post-traumatic stress

disorder (typically related to motor-vehicle accident invol-

vement). panic disorder. or agoraphobia as the psychiatric

disorders most commonly associated with driving phobia

(Taylor & Deane. 1999; Taylor & Deane. 2000). Ehlers et al.

(1994) and Herda. Ehlers and Roth (1993) add social phobia

asacontributingfactoroffearofdriving.

People with Iear oI driving oIten engage in maladaptive

safety behaviors in an attempt to protect themselves from

unpredicted dangers when driving (Antony. Craske & Bar-

low. 1995; Taylor. Deane & Podd. 2007).

About one-fIth oI

accidentsurvivorsdevelopacutestressreactionoutofthis

subgroup. 10 go on to develop a mood disorder. and 20

develop phobic travel anxiety. with 11 developing post-

traumatic stress disorder (Mayou et al.. 1997).

DrivingPhobia

Some controversies lie upon categorizing Iear oI driving.

and some diagnosis as panic disorder. agoraphobia. posttrau-

matic stress disorder. social phobia are considered to be part

oI the driving phobia (Lewis & Walshe. 2005). Although

driving phobia is defned as a specifc phobia in the DSM-

IV (APA. 1994). Blanchard and Hickling (1997) point out

some problems with classifcation: (a) anxiety may be better

accountedforbyanothermentaldisorder(b)anxietymay

not invariably provoke an immediate anxiety response; (c)

36 Psic.: Teor. e Pesq.. Brasilia. Jan-Mar 2010. Vol. 26 n. 1. pp. 35-42

R.T.Costa&Cols.

there may be times when driving does not evoke the parti-

culartriggersrequiredforaphobicresponseand(d)such

responsemaynotberegardedasfearasmuchasasituation

that elicits anxiety and uncomIortable aIIect (Blanchard &

Hickling. 1997; Taylor & Deane 2000).

Another point oI confict is whether or not Iear oI driving

isconsideredacomponentofwideragoraphobicavoidance.

Some authors show that situational panic attacks experienced

by those with specifc phobia are very similar to those with

agoraphobia (Taylor. Deane & Podd. 2000). Others indicate

that driving phobias can also develop after the individual

experiences an unexpected panic attack in the Ieared situation

(Taylor et al.. 2000). Curtis and Himle (citado por Taylor et

al.. 2000) distinguish specifc phobias and agoraphobia in

termsoffocusofapprehension.Individualswithagoraphobia

have avoidance behaviors because they fear panic and its

consequences (anxiety expectancy). whereas people with

specifc phobia Iear danger (danger expectancy) (Antony

Brown & Barlow. 1997; Taylor et al.. 2000).

The onset oI driving-related Iears is attributed to diIIe-

rent variables. Most Irequently. panic attacks are cited as

the onset oI driving Iears (Taylor et al.. 2000). Other cir-

cumstances correspond to traumatic experience (accidents.

dangerous traIfc situations. being assaulted while driving).

seeing someone else experiencing a traumatic event when

driving. being a generally anxious individual and being

generally aIraid oI high speed (Muniack. 1984; Ehlers et

al.. 1994). Other psychological problems reported in road

trauma include irritability. anger. insomnia. nightmares. and

headaches (Blaszczynski. Gordon. Silove. Sloane. Hilman

& Panasetis. 1998).

Interestingly. Taylor and Deane (2000) noticed that many

non-motor vehicle accidents (MVA)-onset driving-IearIuls

individuals have Iears oI similar severity as their MVA-onset

driving-IearIul counterparts. In their research. no signifcant

differenceswerefoundbetweenthesegroupsonmeasures

oI physiological and cognitive symptoms. state anxiety.

degree oI interIerence in daily Iunctioning. prior help Irom

a mental health proIessional. and avoidance oI obtaining a

driverslicense.

Themostfeareddrivingsituationcitedbydrivingpho-

bics is MVA (Blanchard. Hickling. Taylor. Loos & Gerardi.

1994; Blanchard. Hickling. Taylor & Loos. 1995). but they

also mention issues oI control (losing control oI the car. not

being in control oI the driving situation. being in control

oI a powerIul vehicle). specifc driving situations (driving

at high speed. at night. in unIamiliar areas. over bridges.

through tunnels. on steep roads. on open roads. merging. and

changing lanes). and the skills required Ior driving (reaction

time. iudgment errors. weather conditions. road conditions)

(Taylor & Deane. 2000; Taylor et al.. 2000; Taylor et al..

2007b). Concerns about anxiety symptoms while driving

may also be present (Wald & Taylor. 2003). Driving in the

companyofsomeonewhocriticizesonesdrivingwasrated

withthehighestscoreofanxietyandavoidanceinTaylorand

Deane`s study (2000). even though it was unclear whether

therespondentratedaperceivedorrealcriticism.

Cognitive errors are likely to increase Ieelings oI vulne-

rability and maintain anxiety and Iear reactions (Taylor et al..

2007). It is suggested that cognitive errors oI driving phobia

mayinvolvethetendencytooverestimatetheamountoffear

thatwillbeenduredinasubjectivelythreateningsituation

(Rachman & Bichard. 1998). In addiction. people with dri-

ving phobia underestimate their own skills and abilities and

those oI other drivers. As a result. they experience increased

anticipatory anxiety beIore attempting to drive. as well as

avoidance behavior (Koch & Taylor. 1995; Taylor & Deane.

2000). Avoidance behavior may range Irom an occasional

reluctance to drive in particular situations (e.g. heavy traIfc

orbadweather)toaglobalavoidanceofvehiculartravelal-

together.Itcanmaintainphobiasymptomstotheextentthat

it prevents exposure to the Iear stimuli (Taylor et al.. 2007).

Taylor et al. (2007b) used the Driving Cognitions Ques-

tionnaire (DCQ) to detect the most Irequent cognitions oI

fearfulparticipantswhiledriving.Themostrateditemswere

reacting too slowly. being perceived as a bad driver. holding

up traIfc and making people angry. In the same study. so-

cial concerns were evident on the Fear Questionnaire (FQ).

Taylor and Deane (2000) have already mentioned evidence

oI the infuence oI social Iactors in driving Iear. emphasizing

feelingsofhumiliationorembarrassmentasaconsequence

ofperceivednegativeperformanceevaluationbyothers.

VirtualRealityExposureTherapyinthe

TreatmentofDrivingPhobia

According to the emotional processing theory. success-

fulexposuretherapyleadstonewandmoreneutralmemory

structures that overrule the old anxiety-provoking ones

(Foa & Kozak. 1986). II a virtual environment can elicit

Iear responses and activate the anxiety-provoking mecha-

nism. it might be eIIective as an alternative technique to

address exposure interventions. In this sense. VRET can

be a viable alternative to in vivo exposure therapy (Foa &

Kozak. 1986).

Virtual reality exposure integrates real-time computer

graphics. sounds and other sensory inputs to create a com-

puter-generated world with which the individual can interact

(Anderson. Jacobs & Rothbaum.. 2004; Riva. 2002; Riva &

Wiederhold. 2002; Rothbaum & Hodges. 1999; Wiederhold

& Rizzo. 2005). A successIul virtual experience provides

users with a sense oI presence. as though they were physically

immersed in the virtual environment (Gregg & Tarrier. 2007;

Kriin et al.. 2004; Kriin. Emmelkamp. OlaIsson & Biemond.

2004). This sensation is achieved by shutting out 'real world

stimuli so that only computer-generated stimuli can be seen

and heard. Some sensory virtual reality modalities also in-

cludetactileandolfactorysensorystimulationaselementsof

reality (Gregg & Tarrier. 2007; Kriin et al.. 2004b). It has been

observed that. Ior phobic subiects. an increase in the sense oI

presence consequently increases anxiety. On the other hand.

ithasalsobeennoticedthatincreasingstresslevelsincrease

the sense oI presence (Walshe. Lewis & Kim. 2004; Walshe.

Lewis. O`Sullivan & Kim. 2005).

Little controlled treatment research on driving phobia

has been Iound. although some case reports oI accident and

nonaccident-related driving Iear point out that desensitiza-

37 Psic.: Teor. e Pesq.. Brasilia. Jan-Mar 2010. Vol. 26 n. 1. pp. 35-42

RVMedodedirigir

tion can be an eIIective treatment. whereas other studies show

thatvariouscombinationsofinvivoandimaginaryexposure

were successIul (Wald & Taylor. 2003; Taylor et al.. 2007;

Walshe et al.. 2005).

ResultsfromrecentstudiesusingVRET

suggestthatthiswayoftreatmentmightbeappropriatefor

driving phobia (Wald & Taylor. 2000; Wald & Taylor. 2003).

VREThassomepotentialadvantagesoverinvivoand

imaginary exposure. According to Wald and Taylor (2000).

individualswithintensedrivingfearsmayrefusetopartici-

pateininvivoexposureordropoutoftreatmentearly.For

these authors. in vivo exposure has a number oI limitations

and risks because exposure occurs on public roadways. whe-

reas driving situations are oIten unpredictable. time limited.

and diIfcult to control. The authors also assert that in vivo

exposureraisesspecialsafetyandethicalconcernsbecause

highly anxious patients may be at an increased risk oI making

drivingerrorsandbeinginvolvedinaMVAasaconsequence

ofreducedattentionandinformationprocessingcapacities

(Wald & Taylor. 2000).

VRET. on the other hand. occurs in a clinician`s oIfce

sotheconsequencesofdrivingerrorsorunsafeavoidance

behaviors are minimized as well as the risk oI a real motor

vehicle accident. It also reduces potential embarrassment

thatcanbeassociatedwithinitialinvivodrivingexposure.

Otheradvantageisthatfeareddrivingsituationsareableto

be controlled by the clinician. and adiusted. repeated. and

prolonged according to the client`s needs (Wald & Taylor.

2000).

Sometimes. in imaginary exposure. it is diIfcult Ior pho-

bic subiects to imagine a Ieared stimulus. so it is harder to

induce anxiety (Wald & Taylor. 2000). For most individuals.

virtual reality stimuli are more concrete and realistic than

imaginary exposure. reducing the possibility oI avoidan-

ce behaviors. Thus. VRET is mentioned as an alternative

treatment to be used beIore the in vivo exposure (Wald &

Taylor. 2000).

Some limitations are presented in VRET. In some cases.

similar diIfculties as those experienced in imaginary expo-

sure can arise in virtual environments. For some individuals.

Ior example. it might not be suIfciently realistic. so it is

more diIfcult to Ieel the sense oI presence; as a result. the

experience is not real enough to induce anxiety (Walshe et

al.. 2005). According to Wald and Taylor (2003). VRET

has other limitations: it may not be cost-eIIective given the

current cost oI virtual reality technology. it is not widely

accessible to therapists and clients. and sometimes it is not

able to suIfciently target the client`s idiosyncratic driving

Iears (Wald & Taylor. 2003).

Recently. the literature shows a considerable number oI

publications on various aspects of virtual reality exposure

therapy (VRET). which has been applied to the treatment

oI anxiety disorders. especially phobias (Cte & Bouchard.

2005; Jang. Kim. Nam. Wiederhold. Wiederhold & Kim.

2002; Pull. 2005; Rothbaum & Hodges. 1999; Rothbaum.

Hodges & Kooper. 1997; Rothbaum. Hodges & Smith. 1999;

Wilhelm et al.. 2005). The purpose oI this article is to review.

by means oI a systematic methodology. the literature that

supportsthepotentialeffectivenessofVRETinthetreatment

ofdrivingphobia.

Method

A systematic on-line search was perIormed on the

PubMed/Medline and Web oI Science (ISI) databases. The

keywords used in the search were: 'virtual reality and

'Iear oI driving; 'virtual reality and 'driving phobia.

We reviewed articles published between 1984 and 2007.

Among the articles we selected those approaching virtual

reality applied to driving phobia treatment and trials with

VRETforanxietydisorders.Anothersearchwasmadefor

the relevant reIerences cited in these papers. We included

papers in English. Portuguese. French. German and Spanish.

Results

Forty-seven articles were selected and reviewed. oI which

34 dated Irom the last 10 years. Twenty-Iour studies citing

VRET Ior the treatment oI driving phobia were identifed.

Tenstudiestestedthesenseofpresenceinthevirtualenvi-

ronmentsorusedvirtualrealitytechnologiesforthetreatment

oI this Iear. with or without the development and validation

ofanyinstrumentfordrivingfearevaluation.Tenliterature

reviewswereincluded:twoonVRETfordrivingphobiaand

eight on VRET Ior anxiety disorders. UnIortunately. there

arefewsystematicstudiespublishedontheeffectivenessof

VRET in the treatment oI driving phobia. In Iact. only three

papersrepresentedsystematicstudiesonVRETofdriving

phobia (one oI them was a case study). and cause oI that they

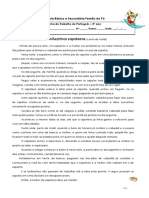

were selected to be described here (see Table 1).

Jang et al. (2002) analyzed non-phobic participants`

physiological reactions to driving and fying virtual envi-

ronments.Elevenparticipantswereexposedtoeachvirtual

environment Ior 15 min. Physiological measures consisted in

heart rate. skin resistance. and skin temperature monitoring.

AIter each exposure. participants were evaluated by means oI

the Presence & Realism Questionnaire (PRQ) and Simulator

Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ). Results demonstrated that

skin resistance and heart rate variability can be used to show

arousal in participants exposed to virtual environments. and.

thereIore. can be used as obiective measures in monitoring

the reaction oI non-phobic participants to these environments.

Theauthorsalsoconcludedthatheartratevariabilitycould

beusefulforassessingtheemotionalstateofparticipants.

One study by Wald and Taylor (2003) examined the eIf-

cacyofVRETfordrivingphobiawithamultiplebaseline

across-subiects experimental design. This design included an

intervention phase consisting oI eight weekly treatment ses-

sions and Iollow-up assessments. Seven adults with a specifc

phobiadiagnosiswererecruitedfromthecommunitybyme-

ansofmediaadvertisements.Fiveparticipantscompletedthe

treatment with 1- and 3-month Iollow-up assessments. From

those fve participants. three showed a decrease in scores on

many oI the outcome measures (see Table 1). and hence. no

longer met the criteria Ior driving phobia at post-treatment.

Thosethreepatientspresentedlossoftreatmentgainsinthe

frst and second Iollow-up assessments. and improvement

in driving Irequency in the last Iollow-up assessment. One

patient showed marginal improvement and another one

38

T

a

b

l

e

1

.

S

t

u

d

i

e

s

o

n

V

i

r

t

u

a

l

R

e

a

l

i

t

y

E

x

p

o

s

u

r

e

T

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

(

V

R

E

T

)

I

o

r

t

h

e

t

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

o

I

d

r

i

v

i

n

g

p

h

o

b

i

a

.

A

u

t

h

o

r

s

P

a

r

t

i

c

i

p

a

n

t

s

G

o

a

l

s

I

n

t

e

r

v

e

n

t

i

o

n

s

N

u

m

b

e

r

o

f

s

e

s

s

i

o

n

s

F

o

l

l

o

w

u

p

E

v

a

l

u

a

t

i

o

n

R

e

s

u

l

t

s

J

a

n

g

e

t

a

l

.

(

2

0

0

2

)

.

1

1

n

o

n

-

p

h

o

b

i

c

s

(

0

F

/

1

1

M

)

T

o

a

n

a

l

y

z

e

n

o

n

-

p

h

o

b

i

c

p

a

r

t

i

c

i

p

a

n

t

s

p

h

y

s

i

o

l

o

g

i

c

a

l

r

e

a

c

t

i

o

n

s

t

o

t

w

o

v

i

r

t

u

a

l

e

n

v

i

r

o

n

m

e

n

t

s

:

d

r

i

v

i

n

g

a

n

d

f

y

i

n

g

.

-

V

R

E

T

1

s

e

s

s

i

o

n

(

1

5

m

i

n

)

N

o

I

o

l

l

o

w

-

u

p

-

P

h

y

s

i

o

l

o

g

i

c

a

l

r

e

s

p

o

n

s

e

(

h

e

a

r

t

r

a

t

e

.

s

k

i

n

r

e

s

i

s

t

a

n

c

e

a

n

d

s

k

i

n

t

e

m

p

e

r

a

-

t

u

r

e

)

-

S

i

m

u

l

a

t

o

r

S

i

c

k

n

e

s

s

Q

u

e

s

t

i

o

n

n

a

i

r

e

(

S

S

Q

)

-

P

r

e

s

e

n

c

e

&

R

e

a

l

i

s

m

Q

u

e

s

t

i

o

n

n

a

i

-

r

e

(

P

R

Q

)

-

T

e

l

l

e

g

e

n

A

b

s

o

r

p

t

i

o

n

S

c

a

l

e

(

T

A

S

)

-

D

i

s

s

o

c

i

a

t

i

v

e

E

x

p

e

r

i

e

n

c

e

s

S

c

a

l

e

(

D

E

S

)

-

S

k

i

n

r

e

s

i

s

t

a

n

c

e

a

n

d

h

e

a

r

t

r

a

t

e

v

a

-

r

i

a

b

i

l

i

t

y

c

a

n

b

e

u

s

e

d

t

o

s

h

o

w

a

r

o

u

s

a

l

o

f

p

a

r

t

i

c

i

p

a

n

t

s

e

x

p

o

s

e

d

t

o

t

h

e

v

i

r

t

u

a

l

e

n

v

i

r

o

n

m

e

n

t

e

x

p

e

r

i

e

n

c

e

.

W

a

l

d

a

n

d

T

a

y

l

o

r

(

2

0

0

3

)

.

5

w

i

t

h

s

p

e

c

i

f

c

p

h

o

b

i

a

d

i

a

g

n

o

-

s

i

s

(

5

F

/

0

M

)

T

o

e

v

a

l

u

a

t

e

t

h

e

e

I

f

c

a

c

y

o

I

V

R

E

T

f

o

r

t

r

e

a

t

i

n

g

d

r

i

v

i

n

g

p

h

o

b

i

a

.

-

V

R

E

T

8

s

e

s

s

i

o

n

s

1

-

3

-

1

2

-

m

o

n

t

h

-

M

a

i

n

T

a

r

g

e

t

P

h

o

b

i

a

a

n

d

G

l

o

b

a

l

P

h

o

b

i

a

I

t

e

m

s

I

r

o

m

t

h

e

F

e

a

r

Q

u

e

s

-

t

i

o

n

n

a

i

r

e

-

D

r

i

v

i

n

g

F

r

e

q

u

e

n

c

y

-

C

l

i

n

i

c

a

l

S

t

r

u

c

t

u

r

e

d

I

n

t

e

r

v

i

e

w

(

S

C

I

D

)

-

T

h

r

e

e

p

a

t

i

e

n

t

s

s

h

o

w

e

d

i

m

p

r

o

v

e

m

e

n

t

i

n

d

r

i

v

i

n

g

a

n

x

i

e

t

y

a

n

d

a

v

o

i

d

a

n

c

e

a

n

d

a

t

p

o

s

t

-

t

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

n

o

l

o

n

g

e

r

m

e

t

c

r

i

t

e

r

i

a

f

o

r

d

r

i

v

i

n

g

p

h

o

b

i

a

-

O

n

e

p

a

t

i

e

n

t

s

h

o

w

e

d

m

a

r

g

i

n

a

l

i

m

p

r

o

-

v

e

m

e

n

t

-

O

n

e

p

a

t

i

e

n

t

s

h

o

w

e

d

n

o

t

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

g

a

i

n

-

L

o

s

s

o

I

t

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

g

a

i

n

s

w

e

r

e

d

e

t

e

c

t

e

d

a

t

f

r

s

t

a

n

d

s

e

c

o

n

d

I

o

l

l

o

w

-

u

p

a

s

s

e

s

s

-

m

e

n

t

s

W

a

l

s

h

e

e

t

a

l

.

(

2

0

0

3

)

.

1

1

w

i

t

h

a

s

p

e

-

c

i

f

c

p

h

o

b

i

a

d

i

a

g

-

n

o

s

i

s

t

h

a

t

e

x

p

e

r

i

e

n

c

e

d

i

m

m

e

r

s

i

o

n

w

h

e

n

e

x

p

o

s

e

d

(

9

F

/

2

M

)

T

o

i

n

v

e

s

t

i

g

a

t

e

t

h

e

e

f

f

e

c

-

t

i

v

e

n

e

s

s

o

f

t

h

e

c

o

m

b

i

n

e

d

u

s

e

o

f

c

o

m

p

u

t

e

r

g

e

n

e

r

a

t

e

d

e

n

v

i

r

o

n

m

e

n

t

s

i

n

v

o

l

v

i

n

g

d

r

i

v

i

n

g

g

a

m

e

s

a

n

d

v

i

r

t

u

a

l

r

e

a

l

i

t

y

d

r

i

v

i

n

g

e

n

v

i

r

o

n

m

e

n

t

i

n

e

x

p

o

s

u

r

e

t

h

e

r

a

p

y

f

o

r

t

h

e

t

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

o

f

d

r

i

v

i

n

g

p

h

o

b

i

a

f

o

l

l

o

w

i

n

g

m

o

t

o

r

v

e

h

i

c

l

e

a

c

c

i

d

e

n

t

p

r

o

g

r

a

m

.

-

V

R

E

T

-

P

h

y

s

i

o

l

o

g

i

c

a

l

I

e

e

d

b

a

c

k

-

D

i

a

p

h

r

a

g

m

a

t

i

c

b

r

e

a

t

h

i

n

g

-

C

o

g

n

i

t

i

v

e

r

e

a

p

-

p

r

a

i

s

a

l

1

2

1

-

h

s

e

s

s

i

o

n

s

N

o

I

o

l

l

o

w

-

u

p

-

P

h

y

s

i

o

l

o

g

i

c

a

l

r

e

s

p

o

n

s

e

(

h

e

a

r

t

r

a

t

e

)

-

S

u

b

i

e

c

t

i

v

e

r

a

t

i

n

g

s

o

I

d

i

s

t

r

e

s

s

(

S

U

D

S

)

-

F

e

a

r

O

I

D

r

i

v

i

n

g

I

n

v

e

n

t

o

r

y

(

F

D

I

)

-

C

l

i

n

i

c

i

a

n

A

d

m

i

n

i

s

t

e

r

e

d

P

T

S

D

s

c

a

l

e

(

C

A

P

S

)

-

H

a

m

i

l

t

o

n

D

e

p

r

e

s

s

i

o

n

S

c

a

l

e

(

H

A

M

-

D

)

A

c

h

i

e

v

e

m

e

n

t

o

f

t

a

r

g

e

t

b

e

h

a

v

i

o

r

s

.

-

T

e

n

o

I

1

1

o

I

t

h

e

d

r

i

v

i

n

g

p

h

o

b

i

c

s

u

b

j

e

c

t

s

m

e

t

t

h

e

c

r

i

t

e

r

i

a

f

o

r

i

m

m

e

r

-

s

i

o

n

/

p

r

e

s

e

n

c

e

i

n

t

h

e

v

i

r

t

u

a

l

d

r

i

v

i

n

g

e

n

v

i

r

o

n

m

e

n

t

.

-

P

o

s

t

-

t

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

r

e

d

u

c

t

i

o

n

s

o

n

a

l

l

m

e

a

s

u

r

e

s

-

P

a

r

t

i

c

i

p

a

n

t

s

e

x

p

a

n

d

e

d

t

h

e

i

r

d

r

i

v

i

n

g

p

r

a

c

t

i

c

e

a

n

d

s

t

a

r

t

e

d

t

r

a

v

e

l

i

n

g

b

y

v

e

h

i

-

c

l

e

w

i

t

h

l

e

s

s

a

n

x

i

e

t

y

39 Psic.: Teor. e Pesq.. Brasilia. Jan-Mar 2010. Vol. 26 n. 1. pp. 35-42

RVMedodedirigir

showed no treatment gains. According to the authors. these

resultssuggestthatVRETisapromisingtreatmentfordriving

phobia. although it may not be suIfcient Ior some patients.

Walshe. Lewis. Kim. O`Sullivan and Wiederhold (2003)

investigatedtheeffectivenessofthecombineduseofcom-

putergeneratedenvironmentsinvolvingdrivinggamesand

avirtualrealitydrivingenvironmentasanexposuretherapy

forthetreatmentofdrivingphobiafollowingamotorvehicle

accident program. Seven subiects. who met the DSM-IV

criteria Ior Simple Phobia/Accident Phobia. experienced

immersionwhenexposedtoavirtualdrivingenvironment

and computer driving games. and they were selected to par-

ticipate in a cognitive behavioral treatment. AIter treatment.

signifcant reductions were Iound in measures oI subiective

distress. driving anxiety. post-traumatic stress disorder rating.

heart rate rise. and depression ratings. The Fear oI Driving

Inventory (FDI) fndings were consistent with clinical reports

inwhitchwhereparticipantswereexpandingtheirdriving

practicesandtravelingbyvehiclewithlessanxiety.Accor-

ding to the authors. Ior some phobic drivers. computer game

realityinducedastrongsenseofpresencesometimestothe

pointofinducingpanic.

Only one case study using virtual reality applications

Ior driving phobia has been reported. Wald and Taylor

(2000) described a case oI a patient who completed three

sessions oI VRET (one hour each). The peak oI anxiety

decreased within and across sessions. In the post-treatment

assessment. her phobic symptoms had diminished and she

no longer met the diagnostic criteria for driving phobia.

Also. the clinical improvement was maintained at 1-. 3-. and

7-month Iollow-up. Evaluation was made by the Structured

Clinical Interview (First. Spitzer. Gibbon & Williams..

1996). the Driving Anxiety Test (an in vivo behavioral

measure). and a driving diary (minutes oI driving per day).

Thiscasestudyreportedsubstantialresults.VRETwassuc-

cessfulinreducingfearofdriving.Ratingsofanxietyand

avoidance declined Irom pre-treatment to post-treatment.

Phobia-related interIerence in daily Iunctioning similarly

decreased. However. more case studies are necessary to

corroborate these fndings.

Discussion

Itwasobservedthatthenumberofsessionsoftreatment

and Iollow up. and the number oI sessions spent on VRET

interventions differed immensely among the described

studies.Componentsofthetreatmentprotocolsalsovaried

among studies. As a consequence. comparing research results

wasimpossible.

Comorbiditieswerenotmentionedinanystudy.Comor-

biditiesareimportantconfoundingfactorsintheevaluation

oI treatment plans and their results. Besides. the studies did

notspecifythenumberofsubjectsonmedicationorthathad

previously attempted any treatmeThe assessment oI specifc

driving variables (e.g.. number oI accidents. years oI driving)

has been rarely reported in the literature. despite the obvious

clinicalrelevanceofthisinformationforconductingacom-

prehensiveassessmentandplanningappropriateintervention

targets. For example. the treatment Ior someone whose

driving fear developed subsequently to the onset of panic

disorder and agoraphobia is likely to be diIIerent Irom the

treatment Ior someone who has always had a specifc phobia

ofdriving.Relevantvariablesofinterestheremayrelateto

the individual`s history as a driver. such as circumstances

surrounding learning to drive. obtaining a driver`s license.

andaccidenthistory.Theindividualsexperienceintheseand

otherareascreatesacomplexsetofconditionsthatneedto

beconsideredindevelopinganinterventionthatistailored

to each client (Taylor et al.. 2007).

Although the data are promising. they suggest that VRET

alone may not be suIfcient in the treatment oI driving phobia

Ior some individuals. VRET may be used as a frst step in the

treatmentforreducingdrivingfeartoadegreeappropriate

forasubsequentinvivoexposuretherapy.

Fearoranxietysymptomscanbeassessedbyobjective

measures: heart rate. peripheral skin temperature. skin

resistance (Jang et al.. 2002). body posture. respiration

rate. brain wave activity (Kriin et al.. 2004b; Wiederhold

& Wiederhold. 1999). or subiective measures. usually the

Subiective Units oI DiscomIort Scale (SUDS) (Kriin et al..

2004b; Wiederhold & Wiederhold. 1999). Generally. VRET

researchers administer a wide range of questionnaires to

evaluate the sense oI presence (Jang et al.. 2002) or driving

cognitions (Ehlers et al.. 2007). Both Iorms oI evaluation

were Iound in these studies. not necessarily administered

together.

Roth (2005) demonstrated that the anxiety oI patients

with situational phobias is accompanied by autonomic.

respiratory. and hormonal changes in the Ieared in vivo

situation. According to Roth (2005) and Alpers. Wilhelm

and Roth (2005). phobics diIIered Irom controls both in

terms oI physiologically and selI-report measures beIore.

during. and aIter in vivo exposure. The physiological

scores were highly congruent with selI-report measures

oI anxiety and decreased over sessions in phobics. what

isinaccordancewiththeexpectedtherapeuticeffectsof

repeated exposure. although the exposures were too Iew to

resultincompleteremission.Theseauthorsshowedsubs-

tantial respiratory disturbances along with the expected

elevations in heart rate and in the Irequency oI non-specifc

skin conductance fuctuations (a variable controlled by the

sympathetic system). In addition. a measure oI respiratory

variability was higher. with hyperventilation. In the study

oI Alpers et al.. salivary cortisol beIore and aIter driving

was greater than that oI control levels. particularly in

the frst exposure session. Also. multiple physiological

measuresofphobicparticipantsandcontrolscontributed

with no redundant inIormation. thus making it possible

an accurate classifcation oI 95 oI phobic and control

participants.

The data mentioned above illustrate the importance of

physiological monitoring. However. none oI the studies used

multiplephysiologicalmeasureswithphobics.Respiratory

variation or salivary cortisol level were not considered in

the analysis oI the eIfcacy oI VRET in Jang et al. (2002).

nevertheless they are effective physiological measures to

assessanxietyandsenseofpresenceinstandardexposure.No

electroencephalographicorneuroimagingdatawerefound

infearofdrivingVRETstudies.

40 Psic.: Teor. e Pesq.. Brasilia. Jan-Mar 2010. Vol. 26 n. 1. pp. 35-42

R.T.Costa&Cols.

FinalConsiderations

Driving phobia is a serious personal and social problem

with several consequences. including career repercussions.

social embarrassment and restrictions. In the treatment of

this disorder. there are some evidences oI the advantages oI

VRETbeforeapplyinginvivoexposuretherapybecauseit

canfunctionasanalternativewaytoinduceexposure.This

idea is supported by some studies in which physiological

measureswereusedtoassesstheeffectivenessofthesense

oI presence (Jang et al.. 2002; Walshe et al.. 2003; Alpers

et al.. 2005). In those studies. the post-treatment showed

reductions in such measures. thus suggesting that VRET has

adirecteffectofhabituation.

Virtual reality oIIers many possibilities Ior psychology.

including assessment. treatment. and research. In the clinical

psychology feld. virtual reality is a saIe. inexpensive. accep-

ted. and probably soon a widespread tool used in exposure

treatments oI phobic disorders. However. more randomized

clinical trials. in which VRET could be compared to standard

exposure. with more obiective measures. are required. We

suggest that Iurther studies should be made. using eIIective

physiological measures in vivo exposure to evaluate the

eIfcacy oI the VRET and the sense oI presence.

References

Alpers. G. W.. Wilhelm. F. H.. & Roth. W. T. (2005).

Psychophysiological assessment during exposure in driving phobic

patients. Journal oI Abnormal Psychology. 114. 126-139.

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and

statistical manual oI mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington. DC:

American Psychiatric Association.

Anderson. P.. Jacobs. C.. & Rothbaum. B. O. (2004). Computer-

supported cognitive behavioral treatment of anxiety disorders.

Journal oI Clinical Psychology. 60. 253-267.

Antony. M. M.. Brown. T. A.. & Barlow. D. H. (1997).

Heterogeneity among specifc phobia types in DSM-IV. Behaviour

Research and Therapy. 35. 1089-1100.

Antony. M. M.. Craske. M. G.. & Barlow. D.H. (1995). Mastery

oI your specifc phobia. San Antonio. TX: The Psychological

Corporation.

Blanchard. E. B.. & Hickling. E. J. (1997). AIter the crash:

Assessment and treatment of motor vehicle accident survivors.

Washington. DC: American Psychological Association.

Blanchard. E. B.. Hickling. E. J.. Taylor. A. E.. & Loos. W.

(1995). Psychiatric morbidity associated with motor vehicle

accidents. Journal oI Nervous and Mental Disease. 183. 495-504.

Blanchard. E. B.. Hickling. E. J.. Taylor. A. E.. Loos. W.. &

Gerardi. R. J. (1994). Psychological morbidity associated with motor

vehicle accidents. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 32. 283-290.

Blaszczynski. A.. Gordon. K.. Silove. D.. Sloane. D.. Hilman.

K.. & Panasetis. P. (1998). Psychiatric morbidity Iollowing motor

vehicleaccidents:Areviewofmetodologicalissues.Comprehensive

Psychiatry. 39. 111-121.

Cte. S.. & Bouchard. S. (2005). Documenting the eIfcacy oI

virtualrealityexposurewithpsychophysiologicalandinformation

processing measures. Applied Psychophysiology and BioIeedback.

30. 217-232.

Ehlers. A.. HoImann. S. G.. Herda. C. A.. & Roth. W. T. (1994).

Clinical characteristics of driving phobia. Journal of Anxiety

Disorders. 8. 323339.

Ehlers. A.. Taylor. J. E.. Ehring. T.. HoIIman. S. G.. Deane.

F. P.. Roth. W. T.. & Podd. J. V. (2007). The driving cognitions

questionnaire: Development and preliminary psychometric

properties. Journal oI Anxiety Disorders. 21. 493-509.

First. M. B.. Spitzer. R. L.. Gibbon. M.. & Williams. J. B. W.

(1996). Structured clinical interview Ior Axis 1 DSM-IV disorders

- Patient edition (Version 2.0). New York: Biometrics Research

Department. New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Foa. E. B.. & Kozak. M. J. (1986). Emotional processing oI

Iear: Exposure to corrective inIormation. Psychol Bullet. 99. 2035.

Colocar nome completo do periodico

Gregg. L.. & Tarrier. N. (2007). Virtual reality in mental

health: A review oI the literature. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric

Epidemiology. 42. 343-54.

Herda. C. A.. Ehlers. A.. & Roth. W. T. (1993). Diagnostic

classifcation oI driving phobia. Anxiety Disorders Practice Journal.

1. 916.

Jang. D. P.. Kim. I. Y.. Nam. S. W.. Wiederhold. B. K..

Wiederhold. M. D.. & Kim. S. I. (2002). Analysis oI physiological

response to two virtual environments: Driving and fying simulation.

Cyberpsychology and Behavior. 5. 11 -18.

Koch. W. J.. & Taylor. S. (1995). Assessment and treatment oI

motor vehicle accident victims. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice.

2. 327-342.

Kriin. M.. Emmelkamp. P. M. G.. Biemond. R.. de Ligny. C. W..

Schuemie. M. J.. & van der Mast. C. A. P. G. (2004a). Treatment oI

acrophobiainvirtualreality:Theroleofimmersionandpresence.

Behaviour Research and Therapy. 42. 229239.

Kriin. M.. Emmelkamp. P. M. G.. OlaIsson. R. P.. & Biemond.

R. (2004b). Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy oI anxiety disorders:

A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 24. 259-281.

Ku. J. H.. Jang. D. P.. Lee. B. S.. Lee. J. H.. Kim. I. Y.. & Kim.

S. I. (2002). Development and validation oI virtual driving simulator

Ior the spinal iniury patient. Cyberpsychology and Behavior. 5.

151-156.

Lewis. E. J.. & Walshe. D. G. (2005). Is video homework oI

beneft when patients don`t respond to virtual reality therapy Ior

driving phobia? Cyberpsychology and Behavior. 8. 342-342.

Mayou. R.. Tyndel. S.. & Bryant. B. (1997). Long-term outcome

oI motor vehicle accident iniury. Psychosomatic Medicine. 59.

578584.

Muniack. D. J.. (1984). The onset oI driving phobias. Journal

oI Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 15. 305308.

Pull. C. B. (2005). Current status oI Virtual Reality Exposure

Therapyinanxietydisorders:Editorialreview.CurrentOpinionin

Psychiatry. 18. 7-14.

Rachman. S.. & Bichard. S. (1998). The overprediction oI Iear.

Clinical Psychology Review. 8. 303-312.

Riva. G. (2002). Virtual reality Ior health care: The status oI

research. Cyberpsychology and Behavior. 5. 219-225.

Riva. G.. & Wiederhold. B. K. (2002). Guest editorial:

Introductiontothespecialissueonvirtualrealityenvironmentsin

behavioral sciences. IEEE TITB. 6. 193-197.

Roth. W. T. (2005). Physiological markers Ior anxiety: Panic

disorder and phobias. International Journal oI Psychophysiology.

58. 190-198.

41 Psic.: Teor. e Pesq.. Brasilia. Jan-Mar 2010. Vol. 26 n. 1. pp. 35-42

RVMedodedirigir

Rothbaum. B. O.. & Hodges. L. F. (1999). The use oI virtual

reality exposure in the treatment oI anxiety disorders. Behavior

modifcation. 23. 507-525.

Rothbaum. B. O.. Hodges. L. F.. & Kooper. R. (1997). Virtual

Reality Exposure Therapy. Journal oI Psychotherapy Practice and

Research. 6. 291296.

Rothbaum. B. O.. Hodges. L.. & Smith. S. (1999). Virtual

RealityExposureTherapyabbreviatedtreatmentmanual:Fearof

fying application. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 6. 234-244.

Taylor. J. E.. & Deane. F. P. (1999). Acquisition and severity

oI driving-related Iears. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 37.

435449.

Taylor. J. E.. & Deane. F. P. (2000). Comparison and

characteristics oI motor vehicle accident (MVA) and non-MVA

driving Iears. Journal oI Anxiety Disorders. 3. 287298.

Taylor. J. E.. Deane. F. P.. & Podd. J. V. (2000). Determining the

Iocus oI driving Iears. Journal oI Anxiety Disorders. 14. 453-470.

Taylor. J.. Deane. F. & Podd. J. (2002). Driving-related Iear: A

review. Clinical Psychology Review. 22. 631-645.

Taylor. J. E.. Deane. F. P.. & Podd. J. V. (2007a). Driving Iear

and driving skills: Comparison between IearIul and control samples

using standardized on-road assessment. Behaviour Research and

Therapy. 45. 805-818.

Taylor. J. E.. Deane. F. P.. & Podd. J. (2007b). Diagnostic

Ieatures. symptom severity. and help-seeking in a media-recruited

sample oI women with driving Iear. Journal oI Psychopatology and

Behavioral Assessment. 29. 81-91.

Wald. J.. & Taylor. S. (2000). EIfcacy oI Virtual Reality

ExposureTherapy to treat driving phobia: a case report. Journal

oI Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 31. 249-257.

Wald. J.. & Taylor. S. (2003). Preliminary research on the

eIfcacy oI Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy to treat driving phobia.

Cyberpsychology and Behavior. 6. 459-465.

Walshe. D. G.. Lewis. E. J.. & Kim. S. I. (2004). Can MVA

victimswithdrivingphobiaimmerseincomputersimulateddriving

environments? Cyberpsychology and Behavior. 7. 317-318.

Walshe. D. G.. Lewis. E. J.. Kim. S. I.. O`Sullivan. K.. &

Wiederhold. B. K. (2003). Exploring the use oI computer games

andVirtualRealityExposureTherapyforfearofdrivingfollowinga

motor vehicle accident. CyberPsychology and Behavior. 6. 329334.

Walshe. D.. Lewis. E.. O`Sullivan. K.. & Kim. S. I. (2005).

Virtually driving: Are the driving environments 'real enough Ior

exposure therapy with accident victims? An explorative study.

Cyberpsychology and Behavior. 8. 532-537.

Wiederhold. B. K.. & Rizzo. A. S. (2005). Virtual reality

and applied psychophysiology. Applied Psychophysiology and

BioIeedback. 30. 183-185.

Wiederhold. B. K.. & Wiederhold. M. D. (1999). Clinical

observations during Virtual Reality Therapy Ior specifc phobias.

Cyberpsychology and Behavior. 2. 161-168.

Wilhelm. F. H.. PIaltz. M. C.. Gross. J. J.. Mauss. I. B..

Kim. S. I.. & Wiederhold. B. K. (2005). Mechanisms oI Virtual

Reality ExposureTherapy:The role of the behavioral activation

and behavioral inhibition systems. Applied Psychophysiology and

BioIeedback. 30. 271-284.

Recebidoem03.05.08

Aceitoem24.10.08!

42 Psic.: Teor. e Pesq.. Brasilia. Jan-Mar 2010. Vol. 26 n. 1. pp. 35-42

R.T.Costa&Cols.

Você também pode gostar

- ExistencialismoDocumento6 páginasExistencialismoLetícia MendesAinda não há avaliações

- Ficha de Trabalho/ Teste NatalDocumento3 páginasFicha de Trabalho/ Teste NatalSandra Lourenço100% (1)

- Galáxia de AndromedaDocumento6 páginasGaláxia de AndromedamaiconboninasAinda não há avaliações

- Repertórido de PagodesDocumento23 páginasRepertórido de PagodesWagner CruzAinda não há avaliações

- As 10 Questões de Genética Mais Importantes Dos Últimos AnosDocumento3 páginasAs 10 Questões de Genética Mais Importantes Dos Últimos AnosVital ViliAinda não há avaliações

- Aula 3 Direito AplicadoDocumento6 páginasAula 3 Direito AplicadoBeatriz OliveiraAinda não há avaliações

- Concurso See/mg Edital 07-2017Documento51 páginasConcurso See/mg Edital 07-2017Jakes Paulo Félix dos Santos100% (2)

- Publico Porto 20170825Documento52 páginasPublico Porto 20170825EsserJorge100% (1)

- OdontopediatriaDocumento45 páginasOdontopediatriaGabriela Gobbo100% (1)

- Cruz Mello (Iamurikuma)Documento335 páginasCruz Mello (Iamurikuma)Cesar GordonAinda não há avaliações

- As Armadilhas de Um Título Rev DSCDocumento12 páginasAs Armadilhas de Um Título Rev DSCMaria PaulaAinda não há avaliações

- Dinamica de Ensaio CoralDocumento17 páginasDinamica de Ensaio CoralLUCASLOBAO90% (10)

- Revelao Da Beleza de JesusDocumento3 páginasRevelao Da Beleza de JesusJose Hoft100% (2)

- Corrimento VaginalDocumento4 páginasCorrimento VaginalPAULO VITOR KELMON SILVA DE OLIVEIRAAinda não há avaliações

- 6 Dimensionamento PDFDocumento34 páginas6 Dimensionamento PDFRodrigoChavesAinda não há avaliações

- Arthur Rimboud - O BARCO ÉBRIO, VOGAIS, MINHA BOÊMIA, AURORADocumento5 páginasArthur Rimboud - O BARCO ÉBRIO, VOGAIS, MINHA BOÊMIA, AURORAJonas de Pinho100% (1)

- Visão Global Da Obra e EstruturaçãoDocumento3 páginasVisão Global Da Obra e EstruturaçãoTeresa SilveiraAinda não há avaliações

- Noções de Direito PenalDocumento48 páginasNoções de Direito PenalDharly Oliveira100% (2)

- Padaria Espiritual: Cultura Popular, Memória e "Uns Pilintras" em Fortaleza No Final Do Século XixDocumento52 páginasPadaria Espiritual: Cultura Popular, Memória e "Uns Pilintras" em Fortaleza No Final Do Século XixMessias Douglas100% (1)

- EBOOK - Atendimento Imobiliário 5.0Documento19 páginasEBOOK - Atendimento Imobiliário 5.0Ayrton RodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- Psicologia de AprendizagemDocumento9 páginasPsicologia de AprendizagemFrancisco Rosario JaimeAinda não há avaliações

- Transtornos Alimentares PDFDocumento29 páginasTranstornos Alimentares PDFGilberto de SouzaAinda não há avaliações

- Resumo-Direito Processual Civil-Aula 18-Peticao Inicial e Admissibilidade-Roberto RosioDocumento3 páginasResumo-Direito Processual Civil-Aula 18-Peticao Inicial e Admissibilidade-Roberto RosioLícia CastroAinda não há avaliações

- Atividade Com o Conto Galinha Ao Molho PardoDocumento5 páginasAtividade Com o Conto Galinha Ao Molho PardonerynasAinda não há avaliações

- Recurso Ordinário PDFDocumento5 páginasRecurso Ordinário PDFSayonara SabinoAinda não há avaliações

- Mat Alg Aula 04 PDFDocumento83 páginasMat Alg Aula 04 PDFDamião PereiraAinda não há avaliações

- Apostila Ensino Fundamental CEESVO - Matemática 03Documento43 páginasApostila Ensino Fundamental CEESVO - Matemática 03Ensino Fundamental95% (20)

- Literatura Descritiva Do Portugues 1Documento1 páginaLiteratura Descritiva Do Portugues 1Chang doveAinda não há avaliações

- Análise Orgulho e PreconceitoDocumento4 páginasAnálise Orgulho e PreconceitoBia MirandaAinda não há avaliações

- Pge - Manual Portal EducacionalDocumento26 páginasPge - Manual Portal EducacionalMg11743222Ainda não há avaliações