Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Decada Do o Ceano

Enviado por

Luciane ReisDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Decada Do o Ceano

Enviado por

Luciane ReisDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Brazilian Journal of Development 66513

ISSN: 2525-8761

Decade of Ocean Science and its relationship with Social-

environmental Oceanography

Década da Ciência Oceânica e sua relação com a Oceanografia

Socioambiental

DOI:10.34117/bjdv7n7-092

Recebimento dos originais: 06/06/2021

Aceitação para publicação: 06/07/2021

Camilah Antunes Zappes

Doutorado em Ecologia e Recursos Naturais

Instituição: Universidade Federal Fluminense/ Instituto de Ciências da Sociedade e

Desenvolvimento Regional, Campos dos Goytacazes

Endereço: Rua José do Patrocínio, 71, centro, Campos dos Goytacazes, RJ. Cep:

28.010-385.

E-mail: camilahaz@yahoo.com.br

Lázaro Dias Alves

Mestrado em Oceanografia Ambiental.

Instituição: Grupo de Pesquisa em Ecologia Humana e Conservação de Recursos

Naturais e Culturais, Instituto de Ciências da Sociedade e Desenvolvimento Regional,

Universidade Federal Fluminense (pesquisador voluntário).

Endereço: Rua José do Patrocínio, 71, centro, Campos dos Goytacazes, RJ. Cep:

28.010-385.

E-mail: lazarodias@id.uff.br

Letícia Guarnier

Mestrado em Oceanografia Ambiental.

Instituição: Programa de Pós-Graduação em Oceanografia Ambiental, Universidade

Federal do Espírito Santo.

Endereço: Av. Fernando Ferrari, 514, Goiabeiras, Vitória, ES. Cep: 29075-900.

E-mail: leticiaguarnier.geo@gmail.com

Nathalia Ribeiro Bignotto

Mestrado em Oceanografia Ambiental.

Instituição: Grupo de Pesquisa em Ecologia Humana e Conservação de Recursos

Naturais e Culturais, Instituto de Ciências da Sociedade e Desenvolvimento Regional,

Universidade Federal Fluminense (pesquisadora voluntária).

Endereço: Rua José do Patrocínio, 71, centro, Campos dos Goytacazes, RJ. Cep:

28.010-385.

E-mail: nathalia.bignotto@gmail.com

Luciane Ayres Castro Reis

Mestrado em Biodiversidade Tropical.

Instituição: Programa de Pós-Graduação em Oceanografia Ambiental, Universidade

Federal do Espírito Santo.

Endereço: Av. Fernando Ferrari, 514, Goiabeiras, Vitória, ES. Cep: 29075-900.

E-mail: lucianeayrescastro@gmail.com

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66514

ISSN: 2525-8761

Cristielli Sorandra Rotta

Programa de Pós-Graduação em Aquicultura.

Instituição: Programa de Pós-Graduação em Oceanografia Ambiental, Universidade

Federal do Espírito Santo.

Endereço: Av. Fernando Ferrari, 514, Goiabeiras, Vitória, ES. Cep: 29075-900.

E-mail: ornamentalcs@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Human interference on coastal and oceanic environments is intense and causes

destruction of ocean habitats. Global actions to contain these negative impacts were

defined in 2017 during the United Nations’ announcement of the Decade of Ocean

Science for Sustainable Development (between 2021 and 2030). During this decade,

actions involving scientists, legislators, public agencies, companies and civil society will

be carried out across the planet, in a joint effort to compile information about the oceans

and define actions towards ocean conservation. These joint efforts will enable countries

to achieve their 2030 Agenda goals focused on the ocean. Socio-environmental

Oceanography, as an interdisciplinary branch of the Ocean Sciences, has an important

role at this time, as it can contribute to the understanding of popular language and

traditional knowledge, in the identification of similarities and discrepancies between

scientific and traditional knowledge and in the promotion of dialogue between different

branches of society. Also, one of the important actions of Socio-environmental

Oceanography is to encourage ocean studies within education, both formal and informal,

in different social strata.

Keywords: Oceans, Conservation, Education, 2030 Agenda.

RESUMO

A interferência humana nos ambientes costeiros e oceânicos é intensa e causa a destruição

dos habitats oceânicos. Ações globais para conter esses impactos negativos foram

definidas em 2017 durante o anúncio das Nações Unidas da Década das Ciências

Oceânicas para o Desenvolvimento Sustentável (entre 2021 e 2030). Durante esta década,

ações envolvendo cientistas, legisladores, órgãos públicos, empresas e sociedade civil

serão realizadas em todo o planeta, em um esforço conjunto para compilar informações

sobre os oceanos e definir ações para a conservação dos oceanos. Estes esforços conjuntos

permitirão que os países alcancem suas metas da Agenda 2030 com foco no oceano. A

Oceanografia Socioambiental, como um ramo interdisciplinar das Ciências Oceânicas,

tem um papel importante neste momento, pois pode contribuir para a compreensão da

linguagem popular e dos conhecimentos tradicionais, na identificação de semelhanças e

discrepâncias entre os conhecimentos científicos e tradicionais e na promoção do diálogo

entre os diferentes ramos da sociedade. Além disso, uma das ações importantes da

Oceanografia Socioambiental é incentivar os estudos oceânicos dentro da educação, tanto

formal quanto informal, em diferentes estratos sociais.

Palavras-Chave: Oceanos, Conservação, Educação, Agenda 2030.

1 OCEANS AND SOCIO-ENVIRONMENTAL OCEANOGRAPHY

Coastal zones are areas that cover up to 100 km from the coastline, with an altitude

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66515

ISSN: 2525-8761

below 100 m above sea level (SMALL; NICHOLLS, 2003). All over the world, these

areas are complex mosaics of coastal ecosystems, where biological, physical, chemical,

geological, meteorological and socio-environmental factors are in constant interaction.

The closer to the coastline, the more these relationships are intensified, due to the

interface between land and sea and the availability of resources that these interactions

offer (CROSSLAND et al., 2005). This set of complex factors allows these environments

to be sources of food, energy, mineral resources, and spaces for leisure, recreation, sports

and religious practices (MEA, 2005).

In these areas, the intense supply of resources is very attractive for human

development. For this reason, coastal areas are the regions with the highest population

density around the world (BALK et al., 2009; NEUMANN et al., 2015; MAUL;

DUEDALL, 2019). A greater population density implies greater pressure on the use of

natural resources, and because these are areas of land-sea interface, coastal environments

are considered fragile, mainly due to the intensification of anthropic activities

(CROSSLAND et al., 2005; MCFADDEN et al., 2007). Projections carried out by the

World Bank found that in the last three decades the population in coastal areas has gone

from 1.6 billion to more than 2.5 billion people, with more than ¾ (1.9 billion) in

developing countries (WBG, 2015). This population growth in coastal areas has

demanded more from coastal ecosystems, which consequently compromises the

maintenance and quality of ecosystem services that benefit people (DELICADO et al.,

2012). Over the last decades, seas and oceans have aroused the interest of researchers

from different areas, especially the lay population. This growth in interest in oceanic

culture is due to the dissemination in television, social media and radio of the increase in

negative interference in coastal areas caused by human activities, such as the reduction

of natural resources and pollution caused by the inadequate disposal of solid waste.

In Brazil, the Coastal and Marine Zone extends from Oiapoque River mouth

(04°52’N) to the Chuí River mouth (33°45’S), and from the limits of the cities located on

the coast up to 200 nautical miles, including the areas surrounding the Atol of Rocas

(03°51’S – 33°48’W), the archipelagos of Fernando de Noronha (03°50’S – 32°25’W),

São Pedro and São Paulo (0°55’S – 29°21’W) and the islands of Trindade and Martin

Vaz (20°29’S – 29°19’W ), located beyond the aforementioned maritime limit (MMA,

2012). The environmental problems on the Brazilian coast are closely linked to the

incentive that the federal government offers to industrial development along the coast.

With the addition of the difficulty and even lack of planning for this economic

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66516

ISSN: 2525-8761

development, the consequence is the intensification of negative impacts on the seas and

oceans and, consequently, a reduction in quality of life of human populations (MEA,

2005; OLIVEIRA et al., 2016; SARTORE et al., 2019; OLIVEIRA et al., 2020).

The problem of coastal environments is even greater due to the complexity of

managing them, especially with aims at sustainable development. The different actors and

users have diverse interests that make it difficult for the management of these

environments (MCLEOD; LESLIE, 2009). Among the tools that enable the improvement

of human development in coastal zones, the dissemination of knowledge, accessible to

society in general and to decision makers, stands out (ABREU et al., 2017; ZAPPES et

al., 2019). However, meeting all the diverse interests for the use of coastal zones is a

challenge, since the management of these zones depends on different institutions, rules

and guidelines, associated with both public and private authorities (CAVALCANTE;

ALOUFA, 2018). In Brazil, there are countless institutions linked, directly or indirectly,

to Integrated Coastal Management, involving both companies and associations and

government agencies, such as Ministries (CAVALCANTE; ALOUFA, 2018).

In this context, in 2002 the term Ocean Literacy – Ocean Culture emerged, based

on partnerships between scientists and educators. Its main objective is to develop

pedagogical resources aimed at teaching the Ocean Sciences. Another important moment

occurred in the year 2017 with the announcement of the Decade of Ocean Science for

Sustainable Development (between 2021 and 2030) by the United Nations (UN)

(UNESCO, 2017). The goal of this decade is to mobilize the scientific community,

legislators, the private sector and civil society for a program for joint research and

technological innovation, one of the objectives of which is to disseminate the importance

of coastal environments so that they are valued. The Decade of Ocean Science will enable

the gathering of information and unifying actions, enabling countries to achieve their

2030 Agenda goals that have to do with the ocean. Achieving these objectives, plans to

ensure health, well-being and food security will be more accessible to countries,

especially developing countries. Also, the Decade of Ocean Science will contribute to

strengthening partnerships, increasing investment in priority areas for conservation

(UNESCO, 2017).

The Decade of Ocean Science emerged in line with the Agenda 2030 Sustainable

Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG 14, “Life Below Water,” which aims to

conserve and promote the sustainable use of oceans, seas and marine resources. From

SDG 14, the need to encourage the participation of the lay society in decision-making

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66517

ISSN: 2525-8761

processes on the use of resources, especially ocean resources, becomes evident. However,

it is necessary to first understand how citizens perceive coastal and ocean environments

from their formation to their use for human activities (UNESCO, 2017).

In the Ocean Sciences, there is a tradition of conducting physical, geological,

biological and chemical studies on coastal and ocean environments in which the human

dimension is still little discussed (MOURA, 2017). In order to increase the discussion on

the role of humans on coastal and ocean ecosystems, a new branch is growing: Socio-

environmental Oceanography (MOURA, 2017; NARCHI et al., 2018; MOURA, 2019).

This new line of study is focused on the human dimension and its relations with the

oceans, seas and coastal areas (MOURA, 2017). Classical oceanography researchers

resist the institution of this new branch with a social bias, which they justify is a topic for

the Humanities. According to these researchers, the human dimension is already

indirectly incorporated into the technical-scientific studies of the Ocean Sciences. These

arguments can limit potential actions and strategies for the Decade of Ocean Science.

Socio-environmental Oceanography allows classic oceanography to act in

discussions on the sustainability of the oceans from the co-management of resources with

society (LUBCHENCO, 1998; MOURA, 2017; NARCHI et al., 2018; MOURA, 2019).

These issues are presented in partnership with the Human and Environmental Sciences,

covering topics related to political ecology and State action in the land, sea and

atmospheric environments (JACQUES, 2010; STONIC; MANDELL, 2007; MOURA,

2017). Research aimed at this new branch can contribute to the understanding of

phenomena studied by other areas of Oceanography, from the combination of traditional

knowledge from communities, scientific knowledge from researchers, and perception of

societies that live close to the coast and use ocean ecosystem services (MOURA, 2017;

2019). In addition, Socio-environmental Oceanography can increase and ensure the

involvement of stakeholders in the elaboration of co-management strategies for the

sustainability of coastal ecosystems (FERNANDES; ZAPPES, 2020). Thus, this new area

of research allows for interdisciplinary discussions and ensures the participation of the

different actors involved (JACQUES, 2010; KELLY et al., 2017; MOURA, 2019).

All areas of Ocean Sciences research contribute to the understanding of impacts

related, for example, to climate change, ocean pollution, loss of ocean species and

degradation of ocean and coastal environments (UNESCO, 2017). In addition to

understanding these biotic and abiotic aspects, it is necessary to consider the cultural

aspect, since the way human populations live interferes in decision-making related to

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66518

ISSN: 2525-8761

sustainability. That is why it is important to encourage the dissemination of oceanic

culture, ensuring that the actors involved are aware of all scenarios (UNESCO, 2017).

In this sense, bringing together traditional and scientific knowledge allows the

expansion of information about coastal and ocean environments, and sustainable actions

practiced by human populations living on the coast can contribute to the co-management

of oceans (ABREU et al., 2017; ALVES et al., 2020). With this co-management, it would

be possible to provide information for the elaboration of public policies and ensure their

effectiveness based on the participation of stakeholders in the mitigation of socio-

environmental conflicts and in the rational use of resources (ARBO; THUY, 2016;

ZAPPES et al., 2016b).

In Brazil, some studies on the Socio-Environmental Oceanography have presented

results and discussions that can contribute to the proposals of SDG 14, demonstrating the

important role of this branch of the Ocean Sciences for coastal and ocean conservation

and maintenance of the quality of human life, as in issues involving: 1) impacts on and

destruction of artisanal fishing territories caused by mega-enterprises at ports

(OLIVEIRA et al., 2016; ZAPPES et al., 2016b), real estate speculation (MUSIELLO-

FERNANDES et al., 2018) and mining companies (OLIVEIRA et al., 2020); 2) use and

commercialization of ocean fishing resources (MUSIELLO- FERNANDES et al., 2017;

BRAGA et al., 2018; CÔRTES et al., 2018; ABREU et al., 2020; BRAGA; ZAPPES,

2021; ZAPPES; FARIA, 2021); 3) interference of climate and oceanic conditions on the

safety and maintenance of artisanal fisheries (ALVES et al., 2018; 2019; 2020); 4)

broadening scientific production involving partnerships between scientific and traditional

knowledge (ZAPPES et al., 2011; 2013a; 2013b; 2014; 2016c; FERNANDES; ZAPPES,

2020); and 5) scientific literacy regarding oceanic culture (ZAPPES et al., 2019).

Despite this, before the Decade of Ocean Science, the production of socio-

environmental studies developed exclusively by ocean scientists in oceanic and coastal

environments was considerably small in the country. In general, scientific production in

the area of Socio-environmental Oceanography is still carried out by researchers from

other areas of scientific knowledge, such as Anthropology (CORDELL, 1974;

MUSSOLINI, 1980; ADOMILLI, 2006); Biology (BEGOSSI, 1995; HAIMOVICI,

2011; ZAPPES et al., 2013a; 2013b; 2016a; 2016c; CÔRTES et al., 2018; MUSIELLO-

FERNANDES et al., 2018; BRAGA; ZAPPES, 2021); Geography (ALVES et al., 2018;

2019; 2020; ABREU et al., 2020; OLIVEIRA et al., 2020); Social Sciences (DIEGUES,

1995); and History (MALDONADO, 1993). The rare contributions of Ocean Sciences

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66519

ISSN: 2525-8761

researchers are a point of criticism in classical Oceanography, as scientists in the area

tend to exclude the humanities (MOURA, 2019). Therefore, it is important for researchers

trained in Ocean Sciences to explore and discuss socio-environmental problems in their

research, since the problems of the oceans, seas and coastal zones are directly or indirectly

linked to human action.

2 OCEAN CULTURE AND SOCIO-ENVIRONMENTAL OCEANOGRAPHY

Although a large portion of the population lives in coastal areas, society is still

unaware of the impacts generated by human activities in coastal and ocean environments.

One of the challenges of the global scientific community is to gather and share knowledge

with diverse audiences. Thus, one of the pillars to improve the human relationship with

these environments involves spreading the ocean culture, that is, promoting educational

actions about oceans.

The dissemination of information about the Ocean Sciences to society is

considered a process of literacy. According to Paulo Freire, literacy allows us to make

connections between the world we live in and the written word (FREIRE, 1967). Thus,

we can use this concept for scientific literacy, which happens when individuals gain

access to interdisciplinary knowledge and scientific discoveries and manage to make

connections with the world around them (ARAGÃO; MARCONDES, 2018). It is also

essential that individuals understand that humans are an integral part of the environment,

and that we influence and are influenced by it (CARVALHO, 2008). This is also one of

the principles of Nature Conservation: knowing nature is a basic premise for conserving

it. Therefore, Freire’s transformative pedagogical concept is fundamental to the socio-

educational processes of Ocean Sciences, as all knowledge in this field is based on socio-

environmental demands. The resolution of problems in the ocean and coastal

environments is an urgent social demand that needs to be inserted in socio-educational

processes, especially in the Decade of Ocean Science.

Thus, at this moment, Socio-environmental Oceanography studies become

important tools for scientific literacy on ocean culture. This is because from studies

involving human and socio-environmental discussions on the coastal and ocean areas, it

will be possible to understand the language used by traditional communities and by

society in general, and in this way, approach and facilitate the dialogue between scientists,

society and managers (ZAPPES et al., 2014; ABREU et al., 2017). Another factor

included in this knowledge dissemination process is related to SDG 4, which advocates

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66520

ISSN: 2525-8761

the promotion of quality education with the involvement of Basic Education schools,

Higher Education and research institutions, non-governmental groups and people who

depend on coastal resources. The theoretical-conceptual and practical use of Socio-

environmental Oceanography can facilitate public educational and environmental

policies, allowing the sharing of information related to coastal-ocean environments

(ZAPPES et al., 2019).

In order for conversations like the one proposed above to be effective, it is

necessary that those involved have knowledge about the problems and conflicts involved

in the atmosphere-continent-ocean interface. The knowledge provided by science can

empower or weaken groups of people who seek environmental quality, as incomplete

information can hinder and even suspend conservation efforts, if the environmental

scenario is unknown (JACQUES, 2010). Therefore, knowledge regarding ocean culture

must be broad, to allow individuals to be: 1) knowledgeable about the ocean; 2) able to

communicate about the ocean in a meaningful way; and (3) able to make decisions about

the use of ocean resources (SANTORO et al., 2017). Since the Decade of Ocean Science

is starting, it is essential that researchers, educators, local actors and managers who work

and/or experience coastal and ocean environments promote ocean literacy.

The oceans are important for the maintenance of life on Earth, but information

about these ecosystems is rarely discussed with the lay population and in formal and

informal education. In this sense, it is essential that the teaching of ocean culture is

inserted in people’s daily lives, proving the importance of combining scientific and

traditional knowledge for greater effectiveness of conservation strategies (ZAPPES et al.,

2019). The dissemination of ocean culture is an important topic, as it positively interferes

in people’s actions, and it is considered a motivator for behavioral changes (POTTS et

al., 2016). This is one of the goals presented in the UNESCO proposal (2017) in the

document on the Decade of Ocean Science, which underscores the importance of

disseminating research results to all the actors involved, thus increasing their participation

in the debates.

Access to scientific content develops logical and critical thinking, in addition to

increasing argumentative abilities. In this sense, understanding the processes that occur

in coastal and oceanic environments through scientific literacy is fundamental for people

to identify the connection between their actions and the ocean. This understanding allows

to increase argumentative capacities in policy discussions, in addition to motivating the

adoption of pro-environmental behaviors (STEEL et al., 2005). However, in order to

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66521

ISSN: 2525-8761

promote scientific literacy involving ocean culture, it is necessary to promote educational

actions based on information about approximation and partnerships that Socio-

environmental Oceanography can provide. Scientific literacy becomes more efficient in

promoting the adoption of sustainable behaviors when associated with motivational

content and social marketing techniques (SCHULTZ, 2011; CIGLIANO et al., 2015).

Another important factor is involving different media, using adapted language and

making topics accessible to a diverse and lay audience, recognizing diversity in cultural

and social values (BAUER et al., 2007). Thus, it is essential to strengthen the bonds

between society and research institutions in which Socio-Environmental Oceanography

as an interdisciplinary area is important, since it can contribute to the understanding of

society, to the intermediation and promotion of dialogues between different social actors,

in addition to provide products to encourage the practice of ocean culture together with

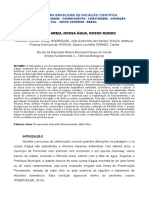

formal and informal education (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Involved in the Decade of Ocean Science and actions of Socio-environmental Oceanography to

achieve the goals of the 2030 agenda.

3 DECADE OF OCEAN SCIENCE AND THE BLUE ECONOMY

The concept of Blue Economy became popular after the United Nations

Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20) held in the city of Rio de Janeiro,

Brazil (SMITH-GODFREY, 2016). This term was used during the conference to align

the economic development of nations with the sustainability of ocean ecosystems. The

need to join development and sustainability is urgent, since the depletion of natural

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66522

ISSN: 2525-8761

resources caused by economic development is a concern of the scientific community

worldwide (FRANCIS, 1990). In contrast, studies show the possibility of sustainable

economic growth from the ocean industry (FISH; WALTON, 2012; KYVELOU;

IERAPETRITIS, 2020).

The discussion involving the Blue Economy strengthens actions to support

compliance with the 2030 Agenda SDGs (SAKER et al., 2018). The SDGs directly

associated with the ocean environment are: 1) Clean water and sanitation (SDG 6) –

emphasizes the need to eradicate the release of domestic waste into ocean ecosystems and

to promote basic sanitation systems for all; 2) Responsible consumption and production

(SDG 12) – the extraction of ocean resources (oil and gas, sand, fishing and minerals)

must respect the sustainable agenda; 3) Climate action (SDG 13) and Life below water

(SDG 14) – since oceans regulate the global climate through the retention of heat and

gases, anthropic interference on these ecosystems deregulates temperatures and

potentiates climate change; 4) Life below water (SDG 14) – through the oceans, human

communities maintain their ways of life and cultural practices, which must be sustainable.

The other SDGs are indirectly associated with the ocean environment, but regardless, they

must be considered in discussions about the Blue Economy.

In Brazil, the application of the Blue Economy principles is fundamental, since

the ocean area under Brazilian jurisdiction is 3.6 million km2, corresponding to

approximately half of the land area of the Brazilian territory (FILHO et al., 2013); in

addition to the diversity of coastal ecosystems in the country. These environments are

exploited in an uncontrolled manner, in disagreement with the Blue Economy principles,

requiring government intervention, especially due to the intense participation Brazil had

in the establishment of the SDGs during Rio+20 (POWERS, 2012).

In this sense, political investment and effective actions by the Brazilian

government in the Blue Economy can encourage other countries participating in the 2030

Agenda, especially in the beginning of the Decade of Ocean Science. However, it is

necessary to involve several segments of society (researchers, public and private sectors

and social movements) to implement projects involving the Blue Economy. This

participation is essential to assess the performance of projects in accordance with the

principles of the 2030 Agenda, in order to meet the SDGs and targets (UN, 2015).

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66523

ISSN: 2525-8761

4 THE ROLE OF SOCIO-ENVIRONMENTAL OCEANOGRAPHY IN THE

DECADE OF OCEAN SCIENCE

The ocean provides the opportunity to address the three pillars that make up

sustainable development: environment, economy and society. However, demonstrating

the human-ocean connection to a society that considers itself separate from nature has

interdisciplinary challenges, as this separatist perception manifests itself in public

management and in programs and actions at various social levels, which consequently

undermines environmental conservation (SCHULTZ, 2002; 2011).

Researchers, managers and local actors believe that actions derived from the

proposal of the Decade of Ocean Science would bring lay citizens closer to the sustainable

needs of oceans. This approach is important, since during the regional workshops for the

construction of the Decade of Ocean Science, popular participation was scarce. This

shows the need for the dissemination of the ocean culture through various media, mainly

social media, which are an important tool for the involvement of the lay public. This

movement of bringing scientists and society together can boost the achievement of the

expected results by 2030, from promoting coastal and ocean conservation to reaching the

SDGs (MACKENZIE et al., 2019; RYABININ et al., 2019). In this sense, Socio-

environmental Oceanography represents an essential interdisciplinary approach to

achieve the objectives of the decade, contributing to the interaction between science and

society (Table 1).

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66524

ISSN: 2525-8761

Table 1. Actions of Socio-Environmental Oceanography and its contributions to the Decade of Ocean Science

How can Socio-environmental Oceanography

Actions Why is it important? Stakeholders

contribute?

To reduce overfishing and maintain sustainable

activities, ensuring the maintenance of fishing Teaching and research

Monitor fishing activities

cultures; to encourage the participation of fishing institutions, institutions and From the understanding of the fishing culture routine and

(This action is related to

communities in political processes that regulate the representatives of fishing way of life of communities that depend on the activity.

goal 14.b of the 2030

co-management of this activity. The participation communities, Non- With the combination of information provided by local

Agenda, and 14.4 and

of local actors in public environmental policies Governmental Organizations, actors, co-management actions can be developed.

14.6 of the 2020 Agenda).

facilitates conservation processes, since those environmental managers.

involved feel they are part of the process.

Teaching and research

Create and expand

institutions, institutions and

protected ocean areas To ensure the protection of ocean environments Developing partnerships with stakeholders, with

representatives of fishing

(This action is related to from co-management and from the use of ocean community involvement in order to optimize and ensure

communities, Non-

goal 14.5 of the 2030 resources in an extractive manner. the protection of ocean environments.

Governmental Organizations,

Agenda).

environmental managers.

Educational and research

Reduce ocean pollution institutions, public managers

To maintain environmental quality and ocean From the promotion of educational activities for literacy

(This action is related to and environmental managers,

ecosystem services, increasing the quality of life of and dissemination of ocean culture with different social

goal 14.1 of the 2025 Non-Governmental

coastal populations. groups.

Agenda). Organizations, conservation

marketing companies.

Understand the effects of To further knowledge about the oceans in their Teaching and research Conducting research related to the perception of tourists

ocean warming, ocean chemical, physical, biological, geological and institutions, tourism managers and local actors on maintaining tourist flow in areas

acidification and climate socio-environmental aspects, and in this way and environmental managers, considered to be impacted by ocean warming and ocean

predictions (This action is contribute to sustainable planning actions that institutions and representatives acidification. Establishing partnerships between academic

related to goal 14.3 of the involve tourism and traditional uses of coastal of traditional communities that organizations and civil society to produce ocean literacy

2030 Agenda). environments. use ocean ecosystem services. material.

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66525

ISSN: 2525-8761

Continuation - Table 1.

How can Socio-environmental Oceanography

Actions Why is it important? Stakeholders

contribute?

Encourage technological

Research institutions, public

innovation in activities that To develop sustainable technologies for the Carrying out perception surveys to identify the

managers, companies that exploit

use ocean resources (This exploitation of ocean resources, ensuring development of sustainable tools and methods used by

ocean resources, and representatives

action is related to goal 14a environmental quality. local actors to capture fishing resources, for example.

from fishing communities.

of the 2030 Agenda).

Promote scientific literacy Conducting scientific dissemination actions on ocean

and dissemination of ocean culture in both formal and informal education.

Scientific literacy strengthens critical

culture based on social Educational and research

thinking, allowing citizens to participate in

demands (This action is institutions, Non-Governmental Training of individuals at different levels (scientific,

environmental decision-making that

related to goal 4.7 of SDG 4 Organizations. governmental, private and public sectors) through

interferes with their quality of life.

– Quality Education, of the short to long-term courses in formal and informal

2030 Agenda). education.

Historical data can help with fundamental

Filling time gaps in Education and research institutions,

information to face current conservation Conducting research based on the combination of

historical data (This action Non-Governmental Organizations,

challenges, as time gaps in information information based on scientific and traditional

is related to goal 14a of the and local actors from traditional

generate uncertainties regarding human knowledge.

2030 Agenda). communities.

impacts on ocean ecosystems.

Identifying, through perception surveys, the adaptive

capacities of coastal populations to face the impacts

Identify and increase caused by ocean risks.

resilience to ocean risks Encouraging education and research institutes and

To identify interferences of these risks to Educational and research

(i.e. storms, coastal erosion, citizens in Citizen Science programs to observe the

human health and to the maintenance of institutions, Non-Governmental

toxic algae proliferation). ocean, with the inclusion of Ethnoclimatology and

traditional activities, such as artisanal fishing, Organizations, and local actors from

(This action is related to Ethno-oceanography data.

for example. coastal populations.

goal 14.2 of the 2020 Developing strategies to translate and transmit

Agenda). information in an accessible language to the lay

public, in order to make the role of science in society

more efficient.

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66526

ISSN: 2525-8761

Continuation - Table 1.

How can Socio-environmental Oceanography

Actions Why is it important? Stakeholders

contribute?

Create innovative public To increase the understanding of decision-

policies and ensure social making processes in coastal and ocean

Educational and research

responses to achieve global environments, in addition to the involvement Encouraging dialogue and partnerships between

institutions, Non-Governmental

sustainability (This action is of interested parties to ensure the practical scientific and traditional knowledge and other

Organizations, conservation

related to goal 11.3 of SDG information necessary in the development of branches of society (co-production and co-

marketing companies, and local

11 - Sustainable cities and sustainable management measures and the dissemination).

actors from coastal populations.

communities, of the 2030 construction of cultural legitimacy to

Agenda). implement actions.

Create a new narrative on the

ocean to motivate the Educational and research

To present to society the causes of the

reduction of pressure and institutions, environmental

impacts to the oceans, so that it is possible to

provide visibility to ocean managers, environmental Use of social marketing techniques to influence pro-

develop solutions joining science and public

science programs (This action marketing companies, and environmental preferences and behaviors.

interest to define decision-making processes

is related to goal 17.17 of representatives from coastal

in coastal and ocean environments.

SDG 17 - Partnerships for the populations.

goals, of the 2030 Agenda).

Developing better methods to implement coastal

Educational and research

To know and define areas and the way in zoning through public participation. Conducting

Ocean Spatial Planning (This institutions, Non-Governmental

which ocean ecosystem services are used, research on participatory mapping and social

action is related to goal 14a Organizations, environmental

ensuring extraction to maintain the way of cartography of coastal areas used by traditional

and b of the 2030 Agenda). managers and representatives from

life of traditional communities. communities and society in general to identify

traditional coastal communities.

possible ocean spatial conflicts.

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66527

ISSN: 2525-8761

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To the Program for Extension of the Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF/PROEX –

Edital Fluxo contínuo 2020/2021 – Process 360730.1927.335487.22102020), to the

Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo a Pesquisa do estado do Rio de Janeiro [grant

number E-26/202.789/2019].

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66528

ISSN: 2525-8761

REFERENCES

ABREU, J. S.; DI BENEDITTO, A. P. M.; MARTINS, A. S.; ZAPPES, C. A. Artisanal

fishing in the municipality of Guarapari, state of Espírito Santo, Brazil: An approach to

the perception of fishermen working in small-scale fishing. Sociedade & Natureza. v.32,

p. 59-74, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.14393/SN-v32-2020-46923.

ABREU, J. S.; DOMIT, C.; ZAPPES, C. A. Is there dialogue between researchers and

traditional community members? The importance of integration between traditional

knowledge and scientific knowledge to coastal management. Ocean & Coastal

Management. v.141, p. 10–19, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.03.003.

ADOMILLI, G. Tempo e espaço: considerações sobre o modo de vida dos pescadores do

Parque Nacional da lagoa do Peixe - RS em um contexto de conflito ambiental.

Iluminuras. v. 01, p. 05-22, 2006.

ALVES, L. D.; BULHÕES, E. M. R.; DI BENEDITTO, A. P. M.; ZAPPES, C. A.

Ethnoclimatology of artisanal fishermen: Interference in coastal fishing in southeastern

Brazil. Marine Policy. v. 95, p. 69-76, 2018.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.07.003.

ALVES, L. D.; DI BENEDITTO, A. P. M.; GHISOLFI, R. D.; QUARESMA, V. S.;

ZAPPES, C. A. Comparisons between ethnooceanographic predictions by fishermen and

official weather forecast in Brazil. Ocean & Coastal Management. v. 198, 105347, 2020.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105347.

ALVES, L. D.; DI BENEDITTO, A. P. M.; ZAPPES, C. A. Ethnooceanography of tides

in the artisanal fishery in Southeastern Brazil: Use of traditional knowledge on the

elaboration of the strategies for artisanal fishery. Applied Geograpgy. v. 110, 102044,

2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2019.102044.

ARAGÃO, S. B. C.; MARCONDES, M. E. R. Fundamentals of Scientific Literacy: A

Proposal for Science Teacher Education Program. Literacy Information and Computer

Education Journal. v. 9, n. 4, p. 3037-3045, 2018.

ARBO, P.; THUY, P. T. T. Use conflicts in ecosystem-based management - The case of

oil versus fisheries. Ocean & Coastal Management. v. 122, p. 77-86, 2016.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2016.01.008.

BALK. D.; MONTGOMERY, M. R.; MCGRANAHAN, G.; KIM, D.; MARA, V.;

TODD, M.; BUETTNER, T.; DORELIEN, A. Mapping urban settlements and the risks

of climate change in Africa, Asia and South America. In: GUZMÁN, J. M.; MARTINE,

G.; MCGRANAHAN, G.; SCHENSUL, D.; TACOLI, C. (Eds.). Population Dynamics

and Climate Change. London: United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), International

Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), 2009. p. 80 – 103.

BAUER, M.; ALLUM, N.; MILLER, S. What can we learn from 25 years of PUS survey

research? Liberating and expanding the agenda. Public Understanding of Science. v.

16, p. 79–95, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0963662506071287.

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66529

ISSN: 2525-8761

BEGOSSI, A. Fishing spots and sea tenure in Atlantic Forest coastal communities.

Humun Ecology. v. 23, n. 3, p. 387-406, 1995.

BRAGA, A. A.; ZAPPES, C. A. Status of traditional knowledge about penaeidae shrimps

and accompanying carcinofauna in Brazil: a bibliographic review. Revista Ibero-

Americana de Ciências Ambientais. v. 12, n. 1, p. 641-650, 2021.

http://doi.org/10.6008/CBPC2179-6858.2021.001.0051.

BRAGA, A. A.; ZAPPES, C. A.; OLIVEIRA, A. C. M. Estudo do conhecimento

tradicional de pescadores do litoral sul do Espírito Santo sobre a carcinofauna

acompanhante da pesca de camarões. Brazilian Journal of Aquatic Science and

Technology. v. 22, n. 2, p. 1-11, 2018.

CARVALHO, I. C. M. Educação ambiental: a formação do sujeito ecológico. São Paulo:

Cortez, 2008.

CAVALCANTE, J. S. I.; ALOUFA, M. A. I. Gerenciamento Costeiro Integrado no

Brasil: Uma Análise Qualitativa do Plano Nacional de Gerenciamento Costeiro.

Desenvolvimento Regional em Debate. v. 8, p. 89-107, 2018.

CIGLIANO, J. A.; MEYER, R.; BALLARD, H. L.; FREITAG, A.; PHILLIPS, T. B.;

WASSER, A. Making marine and coastal Citizen Science matter. Ocean & Coastal

Management. v. 115, p. 77-87, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.06.012.

COCCOSSIS, H. Integrated coastal management and river basin management. Water, Air

& Soil Pollution: Focus. v. 4, n. 4-5, p. 411-419, 2004.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:WAFO.0000044814.44438.81.

CORDELL, J. The lunar-tide fishing cycle in Northeastern Brazil. Ethnology. v. 13, p.

379-392, 1974. https://doi.org/10.2307/3773053.

CROSSLAND, C. J.; BAIRD, D.; DUCROTOY, J.-P.; LINDEBOOM, H.;

BUDDEMEIER, R. W.; DENNISON, W. C.; MAXWELL, B. A.; SMITH, S. V.;

SWANEY, D. P. The Coastal Zone — a Domain of Global Interactions. In:

CROSSLAND, C. J.; KREMER, H. H.; LINDEBOOM, H. J.; MARSHALL

CROSSLAND, J. I.; LE TISSIER, M. D. A. (Eds.). Coastal Fluxes in the

Anthropocene. Global Change — The IGBP Series. Berlim: Springer, 2005. p. 1-34.

CÔRTES, L. H. O.; ZAPPES, C. A.; DI BENEDITTO, A. P. M. The crab harvest in a

mangrove forest in south-eastern Brazil: Insights about its maintenance in the long-term.

Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation. v. 16, p. 113-118, 2018.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecon.2018.02.002.

DELICADO, A.; SCHMIDT, L.; GUERREIRO, S.; GOMES, C. Pescadores,

conhecimento local e mudanças costeiras no litoral Português. Revista da Gestão Costeira

Integrada. v. 12, n. 4, p. 437-451, 2012.

DIEGUES, A. C. S. Povos e mares: uma retrospectiva de sócio-antropologia marítima.

São Paulo: CEMAR, 1995.

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66530

ISSN: 2525-8761

FERNANDES, J. M.; ZAPPES, C. A. Oceanografia socioambiental da pesca artesanal no

estado do Espírito Santo: uma análise bibliométrica. Revista Ibero-Americana de

Ciências Ambientais. v. 11, n. 6, p. 545-558, 2020. http://doi.org/10.6008/CBPC2179-

6858.2020.006.0044.

FILHO, O. D. Q. O.; ARAÚJO, A. M.; MEDEIROS, A. L. R.; ROHATGI, J. S.;

ASIBOR, A. I.; SILVA, H. P. A preliminary approach of the technical feasibility of

offshore wind projects along the Brazilian coast. IEEE Latin America Transactions. v.

11, n. 2, p. 706-712, 2013. http://doi.org/10.1109/TLA.2013.6533958.

FISH, T. E.; WALTON, A. H. Sustainable tourism capacity building for marine protected

areas. Parks. v. 18, n. 2, p. 109-120, 2012.

http://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2012.PARKS-18-2.TEF.en.

FRANCIS, J. G. Natural resources, contending theoretical perspectives, and the problem

of prescription: An essay. Natural Resources Journal. v. 30, n. 2, 263, 1990.

https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nrj/vol30/iss2/2.

FREIRE, P. Educação como prática da liberdade. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Paz e Terra,

1967.

LUBCHENCO, J. Entering the century of the environment: a new social contract for

science. Science. v. 279, n. 5350, p. 491-497, 1998.

http://doi.org/10.1126/science.279.5350.491.

HAIMOVICI, M. Sistemas pesqueiros marinhos e estuarinos do Brasil: caracterização e

análise da sustentabilidade. Rio Grande: Editora da FURG, 2011.

JACQUES, P. J. The social oceanography of top oceanic predators and the decline of

sharks: A call for a new field. Progress in Oceanography. v. 86, p. 192-203, 2010.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2010.04.001.

KELLY, R.; PECL, G. T.; FLEMING, A. Social license in the marine sector: a review of

understanding and application. Marine Policy. v. 81, p. 21-28,

2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.03.005.

KYVELOU, S. S. I.; IERAPETRITIS, D. G. Fisheries Sustainability through soft

multi-use maritime spatial planning and local development co-management:

Potentials and challenges in Greece. Sustainability. v. 12, n. 5, p. 2026, 2020.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052026.

MAUL, G. A.; DUEDALL, I. W. Demography of Coastal Populations. In: FINKL, C.

W.; MAKOWSKI, C. (Eds.). Encyclopedia of Coastal Science. Encyclopedia of Earth

Sciences Series. Cham: Springer, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93806-

6_115.

MACKENZIE, B.; CELLIERS, L.; ASSAD, L.P.D.F.; HEYMANS, J.J.; ROME, N.;

THOMAS, J.; ANDERSON, C.; BEHRENS, J.; CALVERLEY, M.; DESAI, K.;

DIGIACOMO, P.M.; DJAVIDNIA, S.; SANTOS, F.; EPARKHINA, D.; FERRARI, J.;

HANLY, C.; HOUTMAN, B.; JEANS, G.; LANDAU, L.; LARKIN, K.; LEGLER, D.;

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66531

ISSN: 2525-8761

LE TRAON P-Y; LINDSTROM, E.; LOOSLEY, D.; NOLAN, G.; PETIHAKIS, G.;

PELLEGRINI, J.; ROBERTS, Z.; SIDDORN, J.R.; SMAIL, E.; SOUSA-PINTO, I.;

TERRILL, E. The role of stakeholders in creating societal value from coastal and ocean

observations. Frontiers in Marine Science. v. 6, n. 137, 2019.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00137.

MALDONADO, S. C. 1993. Mestres e mares: Espaço e indivisão na pesca marítima. São

Paulo: Anna Blume, 1993.

MCFADDEN, L., NICHOLLS, R., PENNING-ROWSELL, E. Managing coastal

vulnerability. Oxford: Elsevier, 2007.

MCLEOD, K., LESLIE, H. Ecosystem based management for the oceans. Washington:

Island Press, 2009.

MEA - MILLENNIUM ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT. Ecosystems and Human Well-

being: Synthesis. Washington: Island Press, 2005.

MMA - Ministério do Meio Ambiente. Panorama da Conservação dos Ecossistemas

Costeiros e Marinhos no Brasil. Ministério do Meio Ambiente. 2012. Disponível em

<http://200.186.105.177/assets/uploads/livros/livro_panorama_2-marco-2012final.pdf˃.

MOURA, G. G. M. Avanços em oceanografia humana: o socioambientalismo nas

ciências do mar. São Paulo: Paco Editoral, 2017.

MOURA, G. G. M. Construção da crítica à Oceanografia clássica: Contribuições a partir

da Oceanografia Socioambiental. Ambiente & Educação - Revista de Educação

Ambiental. v. 24, n. 2, p. 13-41, 2019. https://doi.org/10.14295/ambeduc.v24i2.9736.

MUSIELLO-FERNANDES, J.; VIEIRA, F. V.; FLORES, R. M.; CABRAL, L.;

ZAPPES, C. A. Pesca artesanal e as interferências sobre a atividade na mesorregião

central do Espírito Santo. Boletim do Museu de Biologia Mello Leitão. v. 40, n. 1, p. 1-

21, 2018.

MUSIELLO-FERNANDES, J.; ZAPPES, C. A.; HOSTIM-SILVA, M. Small-scale

shrimp fisheries on the Brazilian coast: Stakeholders perceptions of the closed season and

integrated management. Ocean & Coastal Management. v. 148, n. 1, p. 89-96, 2017.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.07.018.

MUSSOLINI, G. Ensaios de Antropologia Indígena e Caiçara. Rio de Janeiro: Editora

Paz e Terra, 1980.

NARCHI, N. E.; CARIÑO, M.; MESA-JURADO, M. A.; ESPINOSA-TENORIO, A.;

OLIVOS-ORTIZ, A.; CAPISTRÁN, M. M. E.; MORTEO, E.; OCHOA, Y.; BEITL, C.

M.; DIAZ, T. E. M.; CERVANTES, O.; BRAVO, H. H. N.; SPALDING, A. K.;

GRACEMCCASKEY, C. A.; CORONA, N.; MOURA, G. G. M. El Colaboratorio de

oceanografía social: espacio plural para la conservación integral de los mares y las

sociedades costeras. Ambiente & Sociedade. v. 18, p. 285-301, 2018.

http://doi.org/10.31840/sya.v0i18.1888.

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66532

ISSN: 2525-8761

NEUMANN, B.; VAFEIDIS, A. T.; ZIMMERMANN, J.; NICHOLLS, R. J. Future

Coastal Population Growth and Exposure to Sea-Level Rise and Coastal Flooding - A

Global Assessment. PLoS ONE. v. 10, n. 3, e0118571, 2015.

http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118571.

OLIVEIRA, P. C.; DI BENEDITTO, A. P. M.; BULHÕES, E. M. R.; ZAPPES, C. A.

Artisanal fishery versus port activity in southern Brazil. Ocean & Coastal Management.

v. 129, p. 49-57, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2016.05.005.

OLIVEIRA, P. C.; DI BENEDITTO, A. P. M.; QUARESMA, V. S.; BASTOS, A.

C.; ZAPPES, C. A. Traditional knowledge of Fishers versus an environmental disaster

from mining waste in Central Brazil. Marine Policy. v. 120, 104129, 2020.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104129.

POTTS, T.; PITA, C.; O’HIGGINS, T.; MEE, L. Who cares? European attitudes towards

marine and coastal environments. Marine Policy. v. 72, p. 59–66, 2016.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2016.06.012.

POWERS, A. The Rio+ 20 process: forward movement for the

environment. Transnational Environmental Law. v. 1, n. 2, p. 403-412, 2012.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S2047102512000179.

RYABININ, V.; BARBIÈRE, J.; HAUGAN, P.; KULLENBERG, G.; SMITH, N.;

MCLEAN, C.; TROISI, A.; FISCHER, A.; ARICÒ, S.; AARUP, T.; PISSIERSSENS,

P.; VISBECK, M.; ENEVOLDSEN, H. O.; RIGAUD, J. The UN Decade of Ocean

Science for Sustainable Development. Frontiers in Marine Science. v. 6, n. 470, 2019.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00470.

SANTORO, F.; SANTIN, S.; SCOWCROFT, G.; FAUVILLE, G.; TUDDENHAM, P.

Ocean Literacy for All - A Toolkit. Paris: IOC/UNESCO & UNESCO Venice Office,

2017.

SARKER, S.; BHUYAN, M. A. H.; RAHMAN, M. M.; ISLAM, M. A.; HOSSAIN, M.

S.; BASAK, S. C.; ISLAM, M. M. From science to action: exploring the potentials of

Blue Economy for enhancing economic sustainability in Bangladesh. Ocean & Coastal

Management. v. 157, p. 180–192, 2018. http://doi.org/10.1016/

j.ocecoaman.2018.03.001.

SARTORE, M. S.; PEREIRA, S. A.; RODRIGUES, C. Aracaju beach bars as a contested

market: Conflicts and overlaps between market and nature. Ocean & Coastal

Management. v. 179, p. 828-837, 2019.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.104828.

SMALL, C.; NICHOLLS, R. J. A Global Analysis of Human Settlement in Coastal

Zones. Journal of Coastal Research. v. 19, n. 3, p. 584-599, 2003.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/4299200.

SMITH-GODFREY, S. Defining the Blue Economy. Maritime Affairs: Journal of the

National Maritime Foundation of India. v. 12, n. 1, p. 58-64, 2016.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09733159.2016.1175131.

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66533

ISSN: 2525-8761

STEEL, B. S.; SMITH, C.; OPSOMMER, L.; CURIEL, S.; WARNER-STEEL, R. Public

ocean literacy in the United States. Ocean & Coastal Management. v. 48, n. 2, p. 97–114,

2005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2005.01.002.

STONICH, S.; MANDELL, D. Political ecology and sustainability science: opportunity

and challenge. In: HORNBORG, A.; CRUMLEY, C. (Eds.). The World System and the

Earth System. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, 2007. p. 258-267.

SCHULTZ P. W. Inclusion with Nature: The Psychology Of Human-Nature Relations.

In: SCHMUCK, P., SCHULTZ, W. P. (Eds.). Psychology of Sustainable

Development. Boston: Springer, 2002. p. 61-78. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-

0995-0_4.

SCHULTZ, W. Conservation means behaviour. Conservation Biology. v. 25, n. 6, p.

1080-1083, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2011.01766.x.

UN - United Nations. The Millennium Development Goals Report. 2015. Disponível

em<https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20r

ev%20(July%201).pdf>.

UNESCO - Organização das Nações Unidas para a Educação, a Ciência e a Cultura. The

Science we need for the ocean we want: The United Nations Decade of Ocean Science

for Sustainable Development (2021-2030). 2017. Disponível em

<https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000265198>.

WBG - World Bank Group. Climate Change Impacts on Rural Poverty in Low-Elevation

Coastal Zones. World Bank Group. 2015. Disponível em

<https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/23443>.

WOLLAST, R. Interactions of carbon and nitrogen cycles in the coastal zone. In:

WOLLAST, R.; MACKENZIE, F. T.; CHOU, L. (Eds.). Interactions of C, N, P and S

Biogeochemical Cycles and Global Change. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 1993. NATO

ASI Series I (4), 401-445. 1993. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-76064-8_7.

ZAPPES, C. A.; ALVES, L. D.; DI BENEDITTO, A. P. M. Educação Ambiental

Aplicada à Conservação Costeira: Uma Abordagem da Oceanografia Socioambiental em

Escolas da Rede Pública no Norte do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Revista de Extensão

UENF. v. 4, p. 84-107, 2019.

ZAPPES, C. A.; ALVES, L. C. P. S.; SILVA, C. V.; AZEVEDO, A. F.; DI BENEDITTO,

A. P. M.; ANDRIOLO, A. Accidents between artisanal fisheries and cetaceans on the

Brazilian coast and Central Amazon: Proposals for integrated management. Ocean &

Coastal Management. v. 85, p. 46-57, 2013a.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2013.09.004.

ZAPPES, C. A.; ANDRIOLO, A.; SIMÕES-LOPES, P. C.; DI BENEDITTO, A. P. M.

‘Human-dolphin (Tursiops truncatus Montagu, 1821) cooperative fishery’ and its

influence on cast net fishing activities in Barra de Imbé/Tramandaí, Southern Brazil.

Ocean & Coastal Management. v. 54, n. 5, p. 427-432, 2011.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2011.02.003.

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Brazilian Journal of Development 66534

ISSN: 2525-8761

ZAPPES, C. A.; FARIA, L. A. P. Pescaria coletiva da pescadinha na mesorregião central

do Espírito Santo. Brazilian Journal of Development. v. 7, n. 2, p. 15658-15669, 2021.

http://dx.doi.org/10.34117/bjdv7n2-268.

ZAPPES, C. A.; GAMA, R. M.; DOMIT, C.; GATTS, C. E. N.; DI BENEDITTO, A. P.

M. Artisanal fishing and the franciscana (Pontoporia blainvillei) in Southern Brazil:

ethnoecology from the fishing practice. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of

the United Kingdom. p. 1-11, 2016a. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0025315416001788.

ZAPPES, C. A.; GATTS, C. E. N.; LODI, L. F.; SIMÕES-LOPES, P. C.; LAPORTA, P.;

ANDRIOLO, A.; DI BENEDITTO, A. P. M. Comparison of local knowledge about the

bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus Montagu, 1821) in the Southwest Atlantic Ocean:

New research needed to develop conservation management strategies. Ocean & Coastal

Management. v. 98, p. 120-129, 2014.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2014.06.014.

ZAPPES, C. A.; OLIVEIRA, P. C.; DI BENEDITTO, A. P. M. Percepção de pescadores

do norte fluminense sobre a viabilidade da pesca artesanal com a implantação de

megaempreendimento portuário. Boletim do Instituto de Pesca. v. 42, n. 1, p. 73-88,

2016b. https://doi.org/10.5007/1678-2305.2016v42n1p73.

ZAPPES, C. A.; SILVA, C. V.; PONTALTI, M.; DANIELSKI, M. L.; DI BENEDITTO,

A. P. M. The conflict between the southern right whale and coastal fisheries on the

southern coast of Brazil. Marine Policy. v. 38, p. 428–437, 2013b.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2012.07.003.

ZAPPES, C. A.; SIMÕES-LOPES, P. C.; ANDRIOLO, A.; DI BENEDITTO, A. P. M.

Traditional knowledge identifies causes of bycatch on bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops

truncatus Montagu 1821): An ethnobiological approach. Ocean & Coastal Management.

v. 120, p. 160-169, 2016c. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.12.006.

Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v.7, n.7, p.66513-66534 jul. 2021

Você também pode gostar

- Pão Nosso (Psicografia Chico Xavier - Espírito Emmanuel)Documento192 páginasPão Nosso (Psicografia Chico Xavier - Espírito Emmanuel)karlzenAinda não há avaliações

- Pca - Posto Líder IiDocumento33 páginasPca - Posto Líder IiCésar Roberto Nascimento GuimarãesAinda não há avaliações

- Turfeiras da Serra do Espinhaço Meridional: Serviços Ecossistêmicos Interações Bióticas e PaleoambientesNo EverandTurfeiras da Serra do Espinhaço Meridional: Serviços Ecossistêmicos Interações Bióticas e PaleoambientesAinda não há avaliações

- Bhagavad-Gita: A canção espiritual de KrishnaDocumento145 páginasBhagavad-Gita: A canção espiritual de Krishnajoao AntunesAinda não há avaliações

- Pré-Projeto Educação Ambiental Escola InfantilDocumento12 páginasPré-Projeto Educação Ambiental Escola InfantilAlex Praxedes100% (1)

- 07-Peixes Marinhos PDFDocumento234 páginas07-Peixes Marinhos PDFpc1957Ainda não há avaliações

- Livro - Manejo Integrado de Bacias HidrográficasDocumento302 páginasLivro - Manejo Integrado de Bacias HidrográficasG4LD1N0Ainda não há avaliações

- NR21 Trabalho a céu aberto segurança higieneDocumento11 páginasNR21 Trabalho a céu aberto segurança higieneSergio Antonio GonçalvesAinda não há avaliações

- Transformações energéticas em usinas e dispositivosDocumento33 páginasTransformações energéticas em usinas e dispositivosJackson Bruno100% (1)

- Oceano para Todos, Uma Visão Diferente Da Oceanografia: Ocean For All, A Different Way To See OceanographyDocumento9 páginasOceano para Todos, Uma Visão Diferente Da Oceanografia: Ocean For All, A Different Way To See OceanographyThiago RORIS DA SILVAAinda não há avaliações

- Análise Espacial e Mapeamento Da Ocorrência de Corais Nos Recifes de Picãozinho, João Pessoa-PB, Comparativo Entre 2001 e 2015/2016Documento15 páginasAnálise Espacial e Mapeamento Da Ocorrência de Corais Nos Recifes de Picãozinho, João Pessoa-PB, Comparativo Entre 2001 e 2015/2016Ceciliax SilvaAinda não há avaliações

- Correiaetal2016 Poluioemrecifesdecoraisporvinhotodacana de AcarDocumento25 páginasCorreiaetal2016 Poluioemrecifesdecoraisporvinhotodacana de AcarRenato CorreiaAinda não há avaliações

- Níveis de Elementos Potencialmente Tóxicos Na Água e No Sururu Da Lagoa Mundaú - Alagoas, Brasil - Contaminação Ambiental e Potencial Exposição À Saúde HumanaDocumento102 páginasNíveis de Elementos Potencialmente Tóxicos Na Água e No Sururu Da Lagoa Mundaú - Alagoas, Brasil - Contaminação Ambiental e Potencial Exposição À Saúde HumanaLINQA LINQAAinda não há avaliações

- admin,+BJD+172Documento10 páginasadmin,+BJD+172gabriela.souzaAinda não há avaliações

- 2199-Texto Do Artigo-9840-3-10-20211230Documento5 páginas2199-Texto Do Artigo-9840-3-10-20211230José SousaAinda não há avaliações

- admin,+BJD+art+513Documento17 páginasadmin,+BJD+art+513dinheiroonlineagora2020Ainda não há avaliações

- Cap 1 Lagoa CasamentoDocumento19 páginasCap 1 Lagoa CasamentoAna MastellaAinda não há avaliações

- Trabalho de Submissão Do Lucílio Artigo Clima ARAUCÁRIADocumento13 páginasTrabalho de Submissão Do Lucílio Artigo Clima ARAUCÁRIALucilio MotaAinda não há avaliações

- Trabalho de Submissão Do Lucílio Artigo Clima ARAUCÁRIADocumento13 páginasTrabalho de Submissão Do Lucílio Artigo Clima ARAUCÁRIALucilio MotaAinda não há avaliações

- Resumos Trabalhos Enec 2012Documento204 páginasResumos Trabalhos Enec 2012Juliane MartinsAinda não há avaliações

- Serviçosecossistêmicosprestados Oliveira 2019 PDFDocumento150 páginasServiçosecossistêmicosprestados Oliveira 2019 PDFAlisson OliveiraAinda não há avaliações

- Implementação de ações para a extensão da cultura oceânica na costa nordeste do ParáDocumento14 páginasImplementação de ações para a extensão da cultura oceânica na costa nordeste do ParáLucilio MotaAinda não há avaliações

- Trabalho de Submissão Do Lucílio Artigo ClimaDocumento12 páginasTrabalho de Submissão Do Lucílio Artigo ClimaLucilio MotaAinda não há avaliações

- Zneiman, Artigo13corrigidoDocumento12 páginasZneiman, Artigo13corrigidojeferson.railson05Ainda não há avaliações

- Nascimentoetal 2020Documento11 páginasNascimentoetal 2020Matheus CavalcanteAinda não há avaliações

- BiodiversidadeDocumento113 páginasBiodiversidadeiaque100% (2)

- O Geoprocessamento NoDocumento82 páginasO Geoprocessamento NoNatália ValverdeAinda não há avaliações

- Problemas ambientais e soluções sustentáveis em AlagoinhasDocumento18 páginasProblemas ambientais e soluções sustentáveis em AlagoinhasLu AndradeAinda não há avaliações

- Zneiman, Artigo14Documento20 páginasZneiman, Artigo14Walter Nogueira WalterAinda não há avaliações

- Artigo ProfciambDocumento10 páginasArtigo ProfciambLucilio MotaAinda não há avaliações

- DISSERTAÇÃO João Paulo Gomes de OliveiraDocumento142 páginasDISSERTAÇÃO João Paulo Gomes de Oliveiraluislins1013Ainda não há avaliações

- Holos 1518-1634: Issn: Holos@Documento13 páginasHolos 1518-1634: Issn: Holos@Viviana SanchezAinda não há avaliações

- DocumentDocumento16 páginasDocumentjoseAinda não há avaliações

- Caracterização Físico-Química ÁguaDocumento13 páginasCaracterização Físico-Química ÁguaPaulo DiasAinda não há avaliações

- Manguezais Amazônicos: Evento Vozes do Mangue Promove SensibilizaçãoDocumento16 páginasManguezais Amazônicos: Evento Vozes do Mangue Promove SensibilizaçãoMárcia SantosAinda não há avaliações

- Etnobiologia e Educação Ambiental na Floresta Nacional de NegreirosDocumento10 páginasEtnobiologia e Educação Ambiental na Floresta Nacional de NegreirosALLYSON FRANCISCO DOS SANTOSAinda não há avaliações

- Palestra Conscientização Semana Do Meio Ambiente CN 06 06 23Documento2 páginasPalestra Conscientização Semana Do Meio Ambiente CN 06 06 23FLAVIA GISELE RAMOSAinda não há avaliações

- Vulnerabilidade socioambiental da bacia do Rio CocóDocumento15 páginasVulnerabilidade socioambiental da bacia do Rio CocóJoao Luis Sampaio OlimpioAinda não há avaliações

- 2019 - TCC - Cartografia Social No Cumbe.Documento65 páginas2019 - TCC - Cartografia Social No Cumbe.Ozaias RodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- Texto Do Artigo-1533Documento10 páginasTexto Do Artigo-1533Antares OrionAinda não há avaliações

- 07-Peixes Marinhos PDFDocumento234 páginas07-Peixes Marinhos PDFFINIZOLA64Ainda não há avaliações

- Uma Historia Que A Historia Nao Conta Comunidade DDocumento21 páginasUma Historia Que A Historia Nao Conta Comunidade DKaio CarvalhoAinda não há avaliações

- Projeto Replantio Manguzal Boticário VFDocumento15 páginasProjeto Replantio Manguzal Boticário VFMyreikaFalcaoAinda não há avaliações

- CetaceosDocumento51 páginasCetaceosMatheus SilvaAinda não há avaliações

- Universidade Federal Do Rio Grande Do Sul Instituto de Biociências Programa de Pós-Graduação em EcologiaDocumento178 páginasUniversidade Federal Do Rio Grande Do Sul Instituto de Biociências Programa de Pós-Graduação em EcologiaMylena NecoAinda não há avaliações

- Artigo Pegada EcológicaDocumento9 páginasArtigo Pegada EcológicaAlexandre TinocoAinda não há avaliações

- Coletânea Interdisciplinar em Pesquisa, Pós-Graduação e Inovação - vol. 1: Estudos Ambientais, Território e Movimentos SociaisNo EverandColetânea Interdisciplinar em Pesquisa, Pós-Graduação e Inovação - vol. 1: Estudos Ambientais, Território e Movimentos SociaisAinda não há avaliações

- 172 1041 1 PBDocumento24 páginas172 1041 1 PBRayanne RegisAinda não há avaliações

- Análise do Parque Olhos D'ÁguaDocumento171 páginasAnálise do Parque Olhos D'ÁguaRenzyo CostaAinda não há avaliações

- Tcc-Praias CompletoDocumento16 páginasTcc-Praias Completomkhvz7nmzcAinda não há avaliações

- 11354-Texto Do Artigo-38896-1-10-20201216Documento21 páginas11354-Texto Do Artigo-38896-1-10-20201216tiffany marocoAinda não há avaliações

- Dossiê Amazônia: CiênciaDocumento488 páginasDossiê Amazônia: CiênciaCARLOS SANTOSAinda não há avaliações

- REsiliencia IOVDocumento18 páginasREsiliencia IOVGermano27Ainda não há avaliações

- Burgarelli Aa TCC SvicDocumento55 páginasBurgarelli Aa TCC SvicBaptista Jaime MilioneAinda não há avaliações

- Educação Ambiental A ConscientizaçãoDocumento20 páginasEducação Ambiental A ConscientizaçãoNeto AraujoAinda não há avaliações

- Zoneamento Ecológico Rios Cardoso e CamurupimDocumento154 páginasZoneamento Ecológico Rios Cardoso e CamurupimMauro SousaAinda não há avaliações

- LIVRO Geodiversidade BrasilDocumento268 páginasLIVRO Geodiversidade BrasilLeonardo RangelAinda não há avaliações

- MartineliDocumento8 páginasMartineliLucilio MotaAinda não há avaliações

- O Limiar Da Politica Hab No Brasil - SiqueiraDocumento27 páginasO Limiar Da Politica Hab No Brasil - SiqueiraBrunoAinda não há avaliações

- 10 1016@j Jenvman 2020 110879Documento16 páginas10 1016@j Jenvman 2020 110879Cíntia RibeiroAinda não há avaliações

- Relatório CompletoDocumento12 páginasRelatório CompletoRoberto BuenoAinda não há avaliações

- Livro História Biologia EaDDocumento218 páginasLivro História Biologia EaDAlexandreScheifeleAinda não há avaliações

- Ufes PPGG Douglas Rafael SalaroliDocumento117 páginasUfes PPGG Douglas Rafael Salarolisavio xpAinda não há avaliações

- 1638 5209 3 PBDocumento15 páginas1638 5209 3 PBAkira RainAinda não há avaliações

- Ensino de Ciências e Conservação da Água na AmazôniaDocumento12 páginasEnsino de Ciências e Conservação da Água na AmazôniaGeisiane Patricia Barros LealAinda não há avaliações

- Decada Do o CeanoDocumento22 páginasDecada Do o CeanoLuciane ReisAinda não há avaliações

- Boas práticas de governança para associações e cooperativasDocumento73 páginasBoas práticas de governança para associações e cooperativasLuciane ReisAinda não há avaliações

- Coleta Água ManualDocumento37 páginasColeta Água Manualzimmersecurity2489Ainda não há avaliações

- 1 SMDocumento9 páginas1 SMLuciane ReisAinda não há avaliações

- Echinacea PurpureaDocumento2 páginasEchinacea PurpureaLuciane ReisAinda não há avaliações

- 138 364 1 PB PDFDocumento10 páginas138 364 1 PB PDFMarcos AlmeidaAinda não há avaliações

- Apostila IFES - QuimicaDocumento6 páginasApostila IFES - QuimicaLuciane ReisAinda não há avaliações

- Ecologia de algas perifíticas em lagoa costeira com piscicultura e efluentesDocumento79 páginasEcologia de algas perifíticas em lagoa costeira com piscicultura e efluentesLuciane ReisAinda não há avaliações

- Educação ambiental e conservação da biodiversidadeDocumento6 páginasEducação ambiental e conservação da biodiversidadeMarco Lacerda de OliveiraAinda não há avaliações

- Agentes Quimicos 2Documento47 páginasAgentes Quimicos 2Fabio MottaAinda não há avaliações

- Parque de Inovação Da Serra Catarinense (PISC) - RIMADocumento58 páginasParque de Inovação Da Serra Catarinense (PISC) - RIMASofia SouzaAinda não há avaliações

- Gestão Ambiental da BR-230 reúne DNIT e construtorasDocumento4 páginasGestão Ambiental da BR-230 reúne DNIT e construtorasGlícia FavachoAinda não há avaliações

- GeografiaDocumento5 páginasGeografiaJoanaAinda não há avaliações

- Factor Da Diversidade Das Espécies FaunísticasDocumento2 páginasFactor Da Diversidade Das Espécies FaunísticasKikas JosseneAinda não há avaliações

- Gestão em recursos naturais - Acertos: 4,0 de 10,0Documento4 páginasGestão em recursos naturais - Acertos: 4,0 de 10,0sabrina tairisAinda não há avaliações

- A importância da preservação ambientalDocumento74 páginasA importância da preservação ambientalPaulo JúniorAinda não há avaliações

- Agronegócio exportador e meio ambienteDocumento22 páginasAgronegócio exportador e meio ambienteAna Clea Paiva Morais100% (1)

- A História Da Educação Ambiental - Um Olhar Sobre AngolaDocumento20 páginasA História Da Educação Ambiental - Um Olhar Sobre AngolaGertrudes DembeAinda não há avaliações

- Nutrição e SexualidadeDocumento12 páginasNutrição e Sexualidadeclessiomendes100% (1)

- Orgaooficial 12 1708 1 16032019Documento21 páginasOrgaooficial 12 1708 1 16032019João Romeu MorelliAinda não há avaliações

- Referencial 621277 Operadora-Agrcola ReferencialEFA PDFDocumento148 páginasReferencial 621277 Operadora-Agrcola ReferencialEFA PDFCarlosAinda não há avaliações

- Ecologia HumanaDocumento7 páginasEcologia HumanaLeopoldo Lewis Leo ZimbaAinda não há avaliações

- Limpeza e desinfecção de instalações avícolasDocumento20 páginasLimpeza e desinfecção de instalações avícolasMarcelo CavalcanteAinda não há avaliações

- Roteiros Interpretativos 2020Documento18 páginasRoteiros Interpretativos 2020adrianiAinda não há avaliações

- Alterações Temporais Na Distribuição Dos Diâmetros de Especies ArboreasDocumento17 páginasAlterações Temporais Na Distribuição Dos Diâmetros de Especies ArboreasTati LobattoAinda não há avaliações

- Relat de Atividade Transversal - 201801Documento3 páginasRelat de Atividade Transversal - 201801Marcelo Alves da CruzAinda não há avaliações

- O papel da biblioteca escolar na aprendizagemDocumento6 páginasO papel da biblioteca escolar na aprendizagemEzequiel Passos50% (2)

- Análise Qualitativa Da Utilização Do Co2 Como Método de Recuperação Avançada de Petróleo - Camila PDFDocumento29 páginasAnálise Qualitativa Da Utilização Do Co2 Como Método de Recuperação Avançada de Petróleo - Camila PDFLourival BzzAinda não há avaliações

- Segurança Do Paciente Infantil No Centro CirúrgicoDocumento10 páginasSegurança Do Paciente Infantil No Centro CirúrgicoAna ClementeAinda não há avaliações

- Planejamento Urbano em 40Documento9 páginasPlanejamento Urbano em 40beatrizAinda não há avaliações

- PGS-003279-Gestao de Ruido Ambiental e VibracaoDocumento3 páginasPGS-003279-Gestao de Ruido Ambiental e VibracaoGERANIO DIASAinda não há avaliações

- Aula 3 - A Energia Nos Sistemas EcológicosDocumento34 páginasAula 3 - A Energia Nos Sistemas Ecológicospatriciapereira21Ainda não há avaliações

- Psicologia Organizacional QVTDocumento26 páginasPsicologia Organizacional QVTPeoitoAinda não há avaliações

- Livro ToxicologiaDocumento140 páginasLivro ToxicologiaMarli Lima100% (1)

- Introducao A Ecologia - 2023Documento13 páginasIntroducao A Ecologia - 2023Vinicius PrudencioAinda não há avaliações

- A industrialização e os desafios da sustentabilidadeDocumento13 páginasA industrialização e os desafios da sustentabilidadeJéssica cardosoAinda não há avaliações